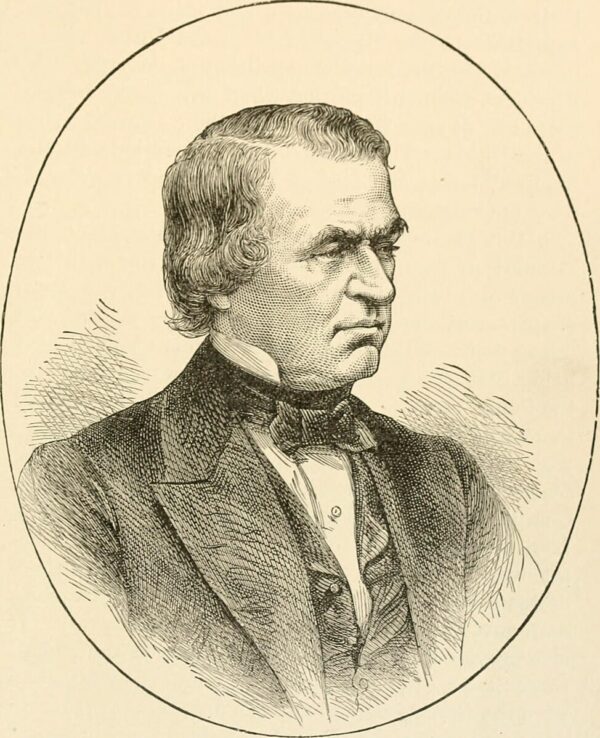

On February 24, 1868, Andrew Johnson, the 17th President of the United States, became the first president ever impeached by the House of Representatives, marking a pivotal moment in American political history. This event was not just the result of partisan rivalry; it emerged from deep ideological conflicts that took root in the aftermath of the Civil War, particularly concerning the future of Reconstruction and the balance of power between the presidency and Congress.

Johnson assumed the presidency after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865. A Southern Democrat from Tennessee who remained loyal to the Union during the war, Johnson initially appeared to be a figure who could unite the fractured nation. However, his vision for post-war America quickly diverged from that of the Republican-dominated Congress, especially the Radical Republicans, who sought to fundamentally reshape Southern society by protecting the rights of newly freed African Americans and reasserting federal control over rebellious states.

Johnson, on the other hand, believed in a lenient approach toward the former Confederate states. His aim was to reintegrate the South swiftly with minimal restrictions, offering pardons generously and opposing policies meant to guarantee civil rights for freedmen. His repeated vetoes of major legislation, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, ignited fierce opposition from Congress, which retaliated by overriding his vetoes and escalating the power struggle between the executive and legislative branches.

The conflict reached its peak with the passage of the Tenure of Office Act in 1867, which was designed to limit the president’s authority to dismiss certain officeholders without Senate approval. This law primarily aimed to protect key allies of Congress, especially Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who was a staunch supporter of Radical Reconstruction. Johnson, believing the law was unconstitutional, defied Congress by attempting to remove Stanton from office and appoint General Lorenzo Thomas as his replacement. This defiance was seen as a direct violation of the Tenure of Office Act and provided Congress with the grounds to initiate impeachment proceedings.

On February 24, 1868, the House of Representatives voted 126 to 47 to impeach Johnson on 11 articles of impeachment. The charges focused primarily on his alleged violation of the Tenure of Office Act, along with accusations of bringing Congress into disrepute through inflammatory speeches and disrespectful conduct. This impeachment was driven as much by political motivations as by legal considerations. Many Radical Republicans viewed Johnson’s removal as essential for ensuring the success of Reconstruction and safeguarding civil rights in the South. However, some lawmakers were concerned that removing a president over political disagreements could set a dangerous precedent that might weaken the executive branch.

When Johnson’s trial moved to the Senate, the outcome hinged on more than just legal evidence—it was influenced by broader political concerns. Ultimately, the Senate fell just one vote short of the two-thirds majority required for conviction. Seven Republican senators broke with their party and voted for acquittal, worried that removing Johnson could destabilize the separation of powers and give Congress excessive authority over the presidency.

Although Johnson narrowly avoided removal from office, his presidency was effectively rendered powerless. He did not secure the Democratic nomination for the 1868 election, and his political influence diminished considerably.

The impeachment of Andrew Johnson established a profound precedent in American constitutional history. It underscored that a president could be impeached for violating laws or undermining Congress, but political motivations would inevitably influence the process. This historic event also highlighted the delicate balance of power between the executive and legislative branches—a tension that continues to shape American governance today.