On March 1, 1845, President John Tyler signed a congressional joint resolution approving the annexation of the Republic of Texas into the United States—an event that profoundly shaped the nation’s territorial growth and foreign policy. The decision marked the culmination of nearly a decade of diplomatic negotiations, sectional conflicts, and escalating tensions with Mexico.

Texas had declared independence from Mexico in 1836 after a successful revolution, and its leaders immediately sought U.S. annexation. However, incorporating Texas into the Union was highly controversial, primarily due to its implications for the balance of power between free and slave states. As a vast territory where slavery was legal, Texas’s admission would strengthen the South’s political influence, further deepening divisions between proslavery and antislavery factions in Congress. Additionally, Mexico, which never formally recognized Texas’s independence, warned that annexation would be seen as an act of war.

For years, the issue remained unresolved. President Andrew Jackson supported Texas but feared immediate annexation would provoke war with Mexico. His successor, Martin Van Buren, opposed it altogether, viewing it as a threat to national unity. By the early 1840s, however, the geopolitical landscape had shifted. Growing British influence in Texas alarmed American expansionists, who feared that Britain might pressure Texas to abolish slavery or establish economic dominance in the region. These concerns, coupled with the increasing popularity of Manifest Destiny—the belief that the United States was destined to expand across the continent—rekindled interest in annexation.

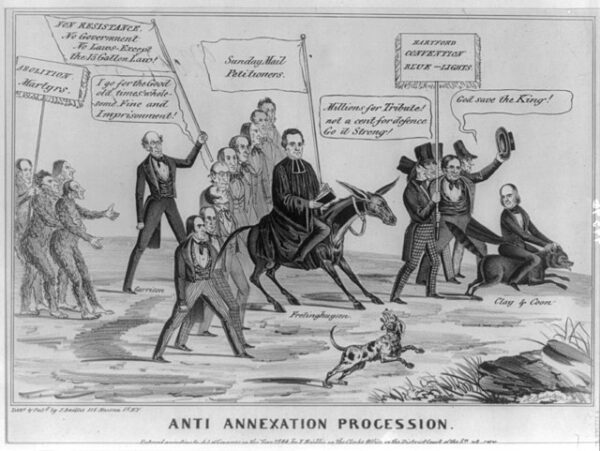

President John Tyler, a strong proponent of expansion, made Texas annexation a priority during his administration. However, his initial attempt to secure a treaty of annexation in 1844 failed in the Senate, largely due to concerns about provoking war with Mexico and expanding slavery. Determined to achieve his goal, Tyler pursued a different strategy: a joint resolution of Congress, which required only a simple majority in both houses instead of the two-thirds majority needed for treaty ratification.

In late February 1845, Congress passed the annexation resolution, thanks to support from Southern Democrats and pro-expansionist Whigs. Eager to solidify his legacy before leaving office, Tyler signed the resolution on March 1—just three days before the end of his presidency. The resolution gave Texas the option of immediate statehood or the ability to retain control over its public lands as a condition of joining the Union.

Although the resolution did not immediately make Texas a state, it set the process in motion. In July 1845, the Texas Congress approved annexation, and in December, Texas officially became the 28th U.S. state. This development further strained relations with Mexico, which still considered Texas a rebellious province, and within a year, the annexation directly led to the Mexican-American War.

Tyler’s signing of the annexation resolution was one of the most significant actions of his presidency, reinforcing his role in U.S. expansion and intensifying sectional tensions. The addition of Texas deepened the national debate over slavery, a conflict that would dominate American politics until the Civil War. Ultimately, Texas’s annexation was more than just a territorial gain—it was a turning point in the broader struggle over the nation’s political and ideological future.