The Wars of the Roses erupted in England during the mid-fifteenth century as a dynastic struggle between the rival houses of Lancaster and York. The conflict stemmed from competing claims to the throne, aristocratic factionalism, and the instability of King Henry VI’s reign. Henry, who inherited the crown as an infant in 1422, proved to be a weak and frequently incapacitated ruler. His periodic mental breakdowns created a power vacuum that allowed Richard, Duke of York—his cousin and a legitimate claimant through the Mortimer line—to challenge his authority. The struggle escalated into open warfare, culminating in a series of battles that ultimately led to a Yorkist victory. The turning point came in early 1461 when Henry VI was deposed, and the Yorkist Edward IV claimed the throne.

By the late 1450s, Henry’s erratic rule emboldened his opponents. Richard, Duke of York, initially acted as Protector of the Realm during Henry’s bouts of incapacity, but he was increasingly marginalized by Henry’s queen, Margaret of Anjou. A determined and ambitious political figure, Margaret sought to secure the throne for her son, Edward of Westminster. York’s challenge to the Lancastrian monarchy led to the first major battle of the conflict at St. Albans in 1455, where his forces were victorious. However, the war continued, and in 1460, after securing victory at the Battle of Northampton, Yorkist forces captured Henry. The Act of Accord, passed in October of that year, attempted to settle the dispute by allowing Henry to remain king while naming York and his heirs as successors, effectively disinheriting the prince. Margaret and her Lancastrian supporters refused to accept this arrangement.

The conflict escalated further in December 1460 when Lancastrian forces defeated York at the Battle of Wakefield, killing him and his second son, Edmund. Queen Margaret then advanced south, defeating Yorkist forces at the Second Battle of St. Albans in February 1461 and recovering King Henry. Despite these victories, the Yorkist cause persisted. York’s eldest son, Edward, Earl of March, emerged as the new leader of the movement. He quickly gathered support, including the backing of the influential Earl of Warwick, known as the “Kingmaker,” and pressed his claim to the throne.

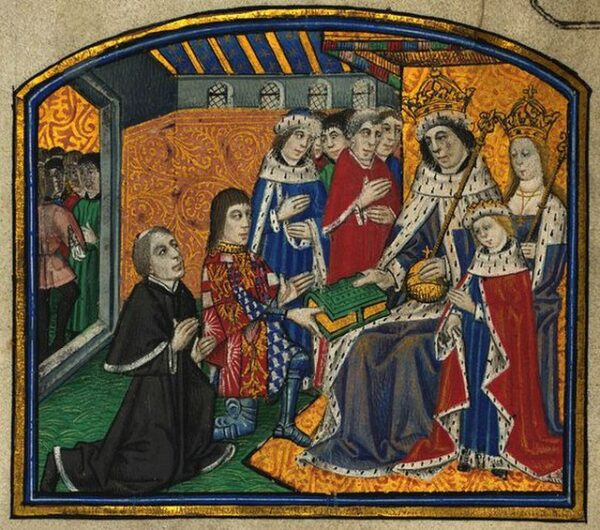

In February 1461, Edward, just eighteen years old, delivered a decisive blow to the Lancastrians at the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross. His victory strengthened his legitimacy, enabling him to march toward London. Meanwhile, despite their recent triumph at St. Albans, Margaret’s forces failed to take the capital, which largely favored the Yorkist cause. As the Lancastrians withdrew northward, Edward entered London unopposed and, with widespread support, declared himself king. On March 4, 1461, he was officially proclaimed King Edward IV, marking the first successful usurpation of the English throne since Henry IV’s rise to power in 1399.

Edward’s claim was not immediately secure, as the Lancastrians regrouped in the north. The decisive battle of the Wars of the Roses took place at Towton on March 29, 1461. In a brutal engagement fought during a snowstorm, Edward’s forces overwhelmed and annihilated the Lancastrian army. Henry VI, Margaret, and their son fled to Scotland, leaving Edward’s throne uncontested. With this victory, the first phase of the Wars of the Roses effectively ended. However, the conflict continued for decades, as Henry’s brief restoration in 1470 and ongoing dynastic struggles kept England in turmoil until the rise of the Tudor dynasty in 1485.

Edward IV’s victory in 1461 marked a turning point in English history, revealing the volatility of kingship and the fragility of dynastic legitimacy. Although his reign began with strength, it later faced significant challenges, including internal Yorkist divisions and continued Lancastrian resistance. These conflicts ultimately paved the way for the emergence of the Tudor dynasty, which would reshape the course of English history.