On the night of April 6, 1712, a group of enslaved Africans lit torches and took to the streets of New York City, launching one of the earliest and most violent slave uprisings in the history of the American colonies. The revolt, centered near what is now the intersection of Broadway and Maiden Lane, shook the foundations of slavery in the urban North and prompted harsh new laws that would reverberate for decades.

At the time, New York City—then a small but growing port town—was home to about 6,000 people. Roughly one in five residents was enslaved. Unlike the plantation slavery that dominated the South, slavery in New York was largely urban. Enslaved people worked as dockworkers, carpenters, blacksmiths, and domestic servants. Many lived in close quarters, allowing ideas—and resentment—to circulate among them.

The roots of the 1712 rebellion lay in both brutality and contradiction. The city’s Black population faced severe oppression: forced labor, physical abuse, family separations, and constant surveillance. But they also lived in proximity to European immigrants and free Black people, and some were permitted to gather in public spaces. These conditions fostered both a sense of community and a burning awareness of injustice.

The revolt was carefully planned. Historians believe more than twenty enslaved men, many of them from West African nations like the Akan-speaking regions, met in secret to coordinate the attack. The uprising began late at night, when the conspirators set fire to a building on the edge of the city, near Broadway. As white townspeople rushed to extinguish the flames, the rebels lay in wait.

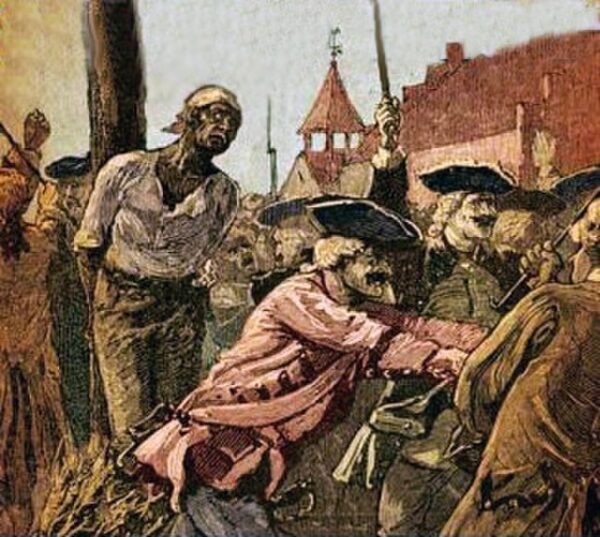

Armed with guns, hatchets, and knives, they ambushed the crowd. Over the course of several minutes, they killed nine white colonists and wounded another six. Panic spread through the city. The colonial militia was called in to suppress the revolt. By morning, most of the rebels had either been killed, captured, or driven into hiding.

What followed was swift and brutal. Governor Robert Hunter established a special tribunal to try the captured slaves. Within a few weeks, more than 70 Black people were arrested. Twenty-seven were put on trial. Of those, twenty-one were convicted and executed in gruesome fashion—some were burned alive, others hanged or broken on the wheel. The spectacle of violence was designed to deter future uprisings and reassert white authority.

The revolt deeply unsettled New York’s white population and prompted a series of harsh new laws. Enslaved people were now forbidden to gather in groups larger than three. They could not carry firearms, gamble, or even move about the city without written permission. Masters were required to punish their slaves more harshly for minor infractions. Most significantly, the rebellion ended any serious legal recognition of manumission—the process by which an enslaved person could be freed.

And yet, the revolt left an enduring mark. It revealed the simmering rage within the enslaved population and forced white colonists to confront the realities of urban slavery. The myth that slavery was somehow milder in the North than in the South began to crack.

Though the 1712 revolt was ultimately suppressed, it foreshadowed future resistance. Just twenty-three years later, in 1741, New York would be gripped by another panic over a supposed slave conspiracy, resulting in dozens of executions based on little more than rumor. The 1712 uprising became a symbol of the constant tension between oppression and resistance, even in the heart of colonial commerce.

Today, the site of the rebellion—near the bustling Financial District—is paved over and largely unmarked. But the memory of that April night endures. It reminds us that even in the earliest days of American slavery, enslaved people resisted—not just with quiet defiance, but sometimes with fire, blood, and revolution.