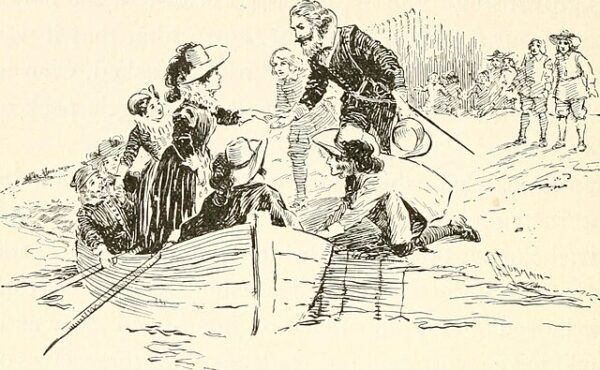

The morning of April 26, 1607, broke clear and bright over the Atlantic. After 144 days at sea, the weary passengers of the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery caught sight of the low, sandy shore of what would become Virginia. With cautious excitement, they lowered small boats and made their way to land — stepping onto a place they would name Cape Henry, after the son of their king.

Few moments in history carry the same mixture of wonder and foreboding. The men, numbering just over a hundred, had crossed an ocean in pursuit of promise: gold, trade, and empire. Backed by the Virginia Company of London, their mission was simple in theory but perilous in fact — to plant an English settlement in a world already inhabited by powerful native nations, and already shadowed by Spanish claims.

The beach at Cape Henry was a marvel. Wildflowers carpeted the dunes, and dense woods stood beyond, alive with game. Birds flocked overhead. For a moment, the hardships of the crossing — the foul water, the cramped holds, the storms — faded from memory. Captain Christopher Newport, commanding the expedition, led a small party ashore carrying a wooden cross. There, in a brief ceremony, they claimed the land for England and for God.

It was an act full of symbolism, but one that could not obscure the reality that this was not empty land. Not long after they came ashore, a group of Native warriors attacked. Arrows flew. Muskets barked in reply. Though the English beat back the attack, the message was clear: they were not welcome. The first blood of the Virginia colony had been spilled before a single dwelling was built.

The settlers had been warned not to make their permanent home too close to the coast. Spanish ships still prowled these waters, and the Powhatan Confederacy, a loose alliance of native tribes under the formidable leadership of Chief Powhatan, controlled much of the interior. Cape Henry was a staging ground, not a destination. After two uneasy nights on the beach, the colonists re-embarked and sailed westward into the great Chesapeake Bay, then up a broad river they named the James.

Within weeks they would found Jamestown — a muddy, mosquito-ridden spot that offered deep-water anchorage and a degree of defensibility. Their suffering had barely begun. Hunger, disease, conflict, and mismanagement would decimate their numbers. Of the 104 who landed at Cape Henry, only a fraction would survive the first year.

Yet that day on the sand, they could not know what lay ahead. They saw only opportunity. The cross they planted symbolized more than possession; it spoke to their belief that they were instruments of divine providence, charged with spreading English civilization and Protestant faith to a new world.

Today, Cape Henry is easily overlooked, tucked away behind the gates of a military base at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. A stone cross and a small monument mark the spot where those first colonists knelt, prayed, and made history. It is a quiet place now, but in 1607, it was the threshold of an enormous unfolding — the start of centuries of exploration, settlement, conflict, and transformation.

In landing at Cape Henry, the Virginia Company settlers crossed not just an ocean, but a dividing line between two eras. They carried with them Old World dreams, fears, and ambitions into a land that would resist, reshape, and ultimately absorb them. The wind on that April day carried the scent of salt and pine — and the future, unknown and vast, stretched before them.