On April 30, 1803, one of the most significant land deals in history was finalized in Paris, France. For a sum of $15 million, the United States purchased the vast Louisiana Territory from France, instantly doubling the size of the young American republic and setting the stage for its westward expansion. The Louisiana Purchase not only redrew the map—it reshaped the destiny of the nation.

At the dawn of the 19th century, the Louisiana Territory was a massive and largely unexplored swath of land stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains and from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian border. Originally claimed by France, it had been ceded to Spain in 1762 after the Seven Years’ War, then quietly returned to French control under Napoleon Bonaparte in 1800. But Napoleon’s dreams of a North American empire quickly soured. His forces were bogged down by a bloody rebellion in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti), and looming war with Great Britain made holding onto distant lands increasingly impractical.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, President Thomas Jefferson was eyeing the strategic port of New Orleans. American farmers west of the Appalachian Mountains relied on the Mississippi River to ship their goods to market, and New Orleans was the key choke point. Fearing French interference with this crucial trade route, Jefferson dispatched James Monroe to join Robert Livingston in France with a simple goal: negotiate the purchase of New Orleans and the surrounding areas for up to $10 million.

To the Americans’ surprise, Napoleon offered much more. Eager to cut his losses and raise funds for war in Europe, the French leader proposed selling the entire Louisiana Territory. The American envoys jumped at the opportunity. On April 30, 1803, they signed a treaty agreeing to purchase the land for $15 million—roughly four cents an acre.

The news stunned Jefferson. Though elated by the scope of the acquisition, he wrestled with a constitutional dilemma. Nowhere did the Constitution explicitly authorize the federal government to purchase new territory. A strict constructionist, Jefferson considered proposing a constitutional amendment—but ultimately concluded that the president’s power to make treaties was sufficient to justify the deal.

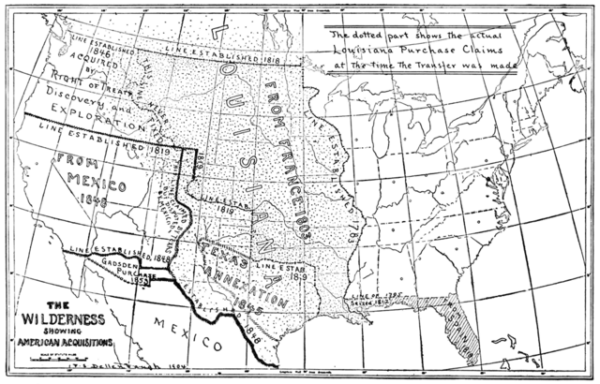

The Louisiana Purchase encompassed approximately 828,000 square miles, adding land that would eventually form all or part of 15 future states, including Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, North and South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas. It gave the United States control of the Mississippi River and the port of New Orleans, securing vital commercial routes for generations to come. But it also raised thorny questions about governance, slavery, Native American rights, and the balance of power between North and South.

Jefferson quickly ordered an expedition to explore the new territory. In 1804, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out on their famed Corps of Discovery, charting the land, cataloging plants and animals, and establishing relations with Native tribes. Their journey symbolized a new era of American ambition, rooted in the belief that the United States was destined to stretch from sea to shining sea.

The Louisiana Purchase marked a turning point not only in American geography but in American identity. It reflected the rising aspirations of a young republic and Jefferson’s vision of a nation of independent farmers, self-sufficient and free. Yet it also foreshadowed the conflicts to come—over expansion, slavery, and the limits of federal power.

Still, for all its complications, the purchase was a staggering bargain. For $15 million, the United States acquired land that would fuel its growth for more than a century. On that spring day in 1803, in the salons of Paris, a deal was struck that would alter the course of American history forever.