On May 4, 1886, the Haymarket Affair, a watershed event marked by ideological conflict and explosive violence, unfolded in Chicago, profoundly shaping America’s political and labor landscape. Occurring amid escalating nationwide tensions driven by a determined campaign for an eight-hour workday, this incident encapsulated the broader struggle of workers against industrial exploitation and oppressive labor conditions, placing the fragility of American democratic ideals into stark relief.

Initially, the assembly at Haymarket Square was peaceful, convened explicitly to protest police violence inflicted days earlier at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, where several workers had been killed. Anarchist leaders, deeply embedded in Chicago’s robust labor movement, organized the event, attracting roughly 1,500 attendees who braved inclement weather to hear impassioned appeals for worker solidarity, justice, and resistance to capitalist oppression.

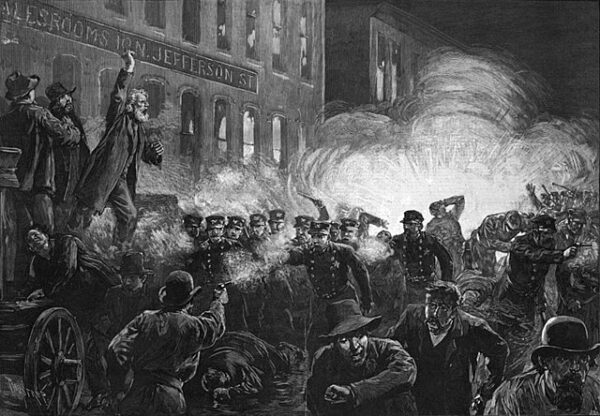

However, the peaceful tenor rapidly deteriorated when Chicago police, led by Captain William Ward, aggressively intervened to disperse the dwindling crowd. As officers advanced around 10:30 PM, an unknown assailant threw a homemade explosive device into their ranks, killing Officer Mathias J. Degan instantly. Chaos ensued as panicked police responded with indiscriminate gunfire, escalating violence that ultimately resulted in the deaths of seven additional policemen and four civilians, alongside numerous injuries sustained on both sides.

The immediate aftermath of the Haymarket bombing was characterized by swift, sweeping, and contentious legal reprisals. Authorities, driven more by public hysteria and fear of radical political ideologies than by concrete evidence, swiftly arrested eight prominent anarchists and socialists: Albert Parsons, August Spies, Samuel Fielden, Michael Schwab, Adolph Fischer, George Engel, Louis Lingg, and Oscar Neebe. Their trial, condemned broadly by contemporaries and historians alike as overtly prejudicial, epitomized prevailing anxieties surrounding radicalism, immigration, and labor activism perceived as threats to social order.

Seven defendants were sentenced to death; Neebe received a lengthy prison term. Lingg died by suicide in his jail cell before execution. On November 11, 1887, Parsons, Spies, Fischer, and Engel were executed by hanging, an event that sparked international outrage and galvanized labor advocates worldwide. The remaining defendants were eventually pardoned in 1893 by Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld, whose courageous critique of the judicial proceedings as a miscarriage of justice provoked both fierce denunciation and widespread acclaim, illustrating the deep ideological rifts within American society.

The enduring significance of Haymarket lies in its profound impact on the labor movement. In its immediate aftermath, public opinion turned sharply against labor activism, associating unionization and social reform with violent radicalism, thereby hindering labor organizing efforts for decades. Yet paradoxically, for labor supporters worldwide, the executed men became martyrs, emblematic of their ongoing fight for economic and social justice, significantly contributing to the institutionalization of May 1 as International Workers’ Day.