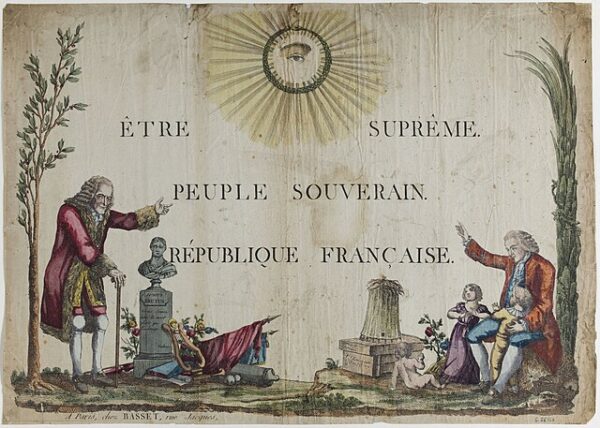

In the blood-soaked spring of 1794, as guillotines claimed heads by the dozen and the French Revolution threatened to devour itself, Maximilien Robespierre unveiled his most audacious experiment yet—not in law or terror, but in theology. On May 7, standing before the National Convention, the architect of the Reign of Terror proposed a new state religion: the Cult of the Supreme Being. It was not a return to Catholicism, nor a full surrender to the militant atheism of his radical peers—it was, instead, a calculated effort to infuse the Republic with moral order, patriotic unity, and a higher purpose beyond the guillotine.

For Robespierre, a lawyer turned messianic revolutionary, civic virtue required more than force; it needed faith—not in dogma or priests, but in a reasoned, deistic god who rewarded justice and punished corruption. Influenced by Rousseau’s social contract and gripped by the belief that morality was essential to political survival, he envisioned a republic undergirded not by superstition or nihilism but by a sense of cosmic accountability. In this view, the Church had been an agent of tyranny, and the Hébertists’ Cult of Reason—an anarchic, godless spectacle—offered only moral rot in its place. What Robespierre offered instead was a middle path: a new spiritual scaffolding to hold the nation together.

In his speech, Robespierre declared that belief in a Supreme Being and the immortality of the soul were not optional embellishments—they were the bedrock of a virtuous republic. Citizens, he argued, must be reminded that liberty without morality becomes license, and that the Revolution’s bloodshed demanded ethical justification rooted in something higher than human ambition. A state religion, stripped of clerical power but rich in symbolism, could channel collective sacrifice into transcendent purpose.

The Convention approved his decree the same day. France, officially, now acknowledged a Supreme Being, and public festivals would be held in his honor. The centerpiece was the Festival of the Supreme Being, scheduled for June 8—a grand, choreographed display of national unity and moral rebirth. Robespierre personally staged it with theatrical flair, marching before papier-mâché mountains and delivering sermons in flowing robes. But what was meant to inspire awe instead sparked whispers: had the incorruptible turned into a high priest of his own cult?

The backlash was swift and fatal. To Catholics, the Cult was a hollow parody of true faith. To radicals, it was a betrayal of secularism. And to Robespierre’s enemies—who were growing in number—it was further proof of his delusions of grandeur. The June festival, far from cementing his role as moral savior, painted a target on his back. Less than two months later, he was arrested and executed during the Thermidorian Reaction, and with him died the Cult he had fathered.