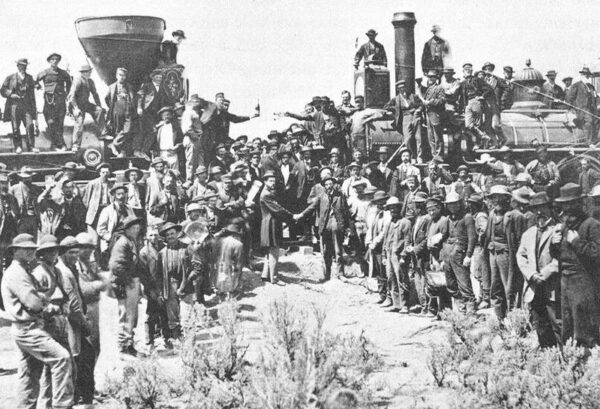

On May 10, 1869, in the arid expanse of Utah Territory at a place called Promontory Summit, two locomotives faced each other across a polished laurel tie as dignitaries and railroad workers looked on. Then, with the ceremonial tapping of a golden spike into a pre-drilled hole, the First Transcontinental Railroad was declared complete—a singular feat of engineering, ambition, and brute labor that irrevocably altered the American West and stitched together a fractured nation.

The railroad had been conceived during war but born in the language of peace and expansion. Authorized by the Pacific Railway Act of 1862 and signed by Abraham Lincoln in the dark hours of the Civil War, the legislation deputized two companies—the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific—to race toward each other from opposite ends of the continent, carving parallel paths across mountains, deserts, and tribal lands. Lavish land grants and federal bonds greased the wheels, offering not just a means of construction but a vision: a commercial and cultural artery uniting East and West.

That vision came at immense human cost. The Central Pacific, clawing eastward from Sacramento, faced the granite spine of the Sierra Nevada—an obstacle so unforgiving it required Chinese laborers, some 12,000 strong at peak, to drill and blast their way through with nitroglycerin and iron will. Paid less than white workers and living in segregated camps, they worked through avalanches, rockslides, and relentless snow. The Union Pacific, forging westward from Omaha under the command of Grenville Dodge, moved faster across the plains but no less perilously—fending off labor unrest, dysentery, and attacks from Native tribes defending land never ceded. Its workforce included Irish immigrants, freedmen, and displaced Civil War veterans—men worn down by one great struggle only to be enlisted in another.

When the two rails met after six relentless years, the nation paused to celebrate. The hammer stroke that missed the first time—Leland Stanford’s—mattered little. What mattered was the signal flashed along telegraph wires nationwide: “DONE.” Cheers rang out from the stockyards of Chicago to the wharves of San Francisco. In this golden moment, America had conquered its geography—or so the story went.

But the truth was more complicated. The railroad shortened coast-to-coast travel from months to mere days and opened vast commercial possibilities, turning cattle into cargo and towns into trading posts. Yet it also hastened the destruction of Native nations and the bison herds that had sustained them for centuries. The very tracks that carried progress also carried settlers, soldiers, and surveyors—agents of dispossession cloaked in the promise of Manifest Destiny. Treaties were broken, resistance crushed, and cultures upended—all in the name of connection.

Nor was the railroad immune to the rot of political and financial corruption. The Crédit Mobilier scandal, in which lawmakers and executives siphoned public funds under the guise of railroad construction, exposed the darker symbiosis between government largesse and private greed. Much of the line would later need to be rebuilt—hastily laid tracks replaced, trestles reinforced, corners squared.

Still, the symbolic power of that day at Promontory Summit endures. Today, the Golden Spike National Historical Park preserves the site as hallowed ground—not just for what was gained, but for what it cost. The railroad did more than link coasts. It inaugurated a new era of national identity, rooted in movement, enterprise, and expansion. But like so many American triumphs, it was shadowed by sacrifice—its golden spike glinting not only with pride, but with the weight of all it buried.