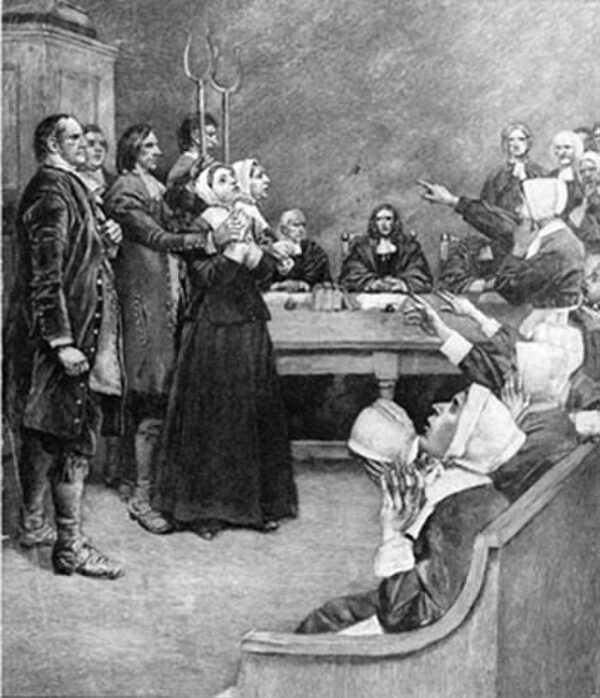

In a bizarre legal footnote to American religious history—and a final echo of the spectral hysteria that once gripped colonial New England—the last case resembling a witchcraft trial in the United States began not in the 17th century, but in 1878. Nearly two centuries after the gallows at Gallows Hill fell silent, Salem once again found itself at the intersection of law, metaphysics, and fear. But this time, the charge was not sorcery—it was mental malpractice. And the accused was not a wart-nosed crone muttering incantations, but a man: Daniel H. Spofford, a disaffected disciple of Mary Baker Eddy, founder of Christian Science.

The plaintiff, Lucretia L. S. Brown, was an invalid from Ipswich and a devoted follower of Eddy’s teachings, which rejected conventional medicine in favor of spiritual healing through mental discipline and divine understanding. On May 14, 1878, Brown filed suit in the Essex County Superior Court, alleging that Spofford, acting through “mesmeric” influence, had intentionally afflicted her, disrupting her recovery and inflicting mental and physical torment. In short, she claimed he had psychically assaulted her.

But the real stakes of Brown v. Spofford had little to do with Brown’s spinal ailment or Spofford’s alleged “malicious animal magnetism.” At issue was the very coherence and authority of Christian Science itself, then in its formative years. Spofford had once been a favored student of Eddy and a leader at her Massachusetts Metaphysical College. But he broke with her over theological and organizational differences, publicly questioning her control over the movement and its doctrines. Eddy, in turn, denounced him. While she never appeared in court, her fingerprints were all over the case. Brown, her loyal adherent, had sought the court’s intervention to restrain Spofford’s psychic interference. Behind the scenes, Eddy’s interest in expelling dissent and consolidating her authority was unmistakable.

In her complaint, Brown accused Spofford of exercising “mental powers” to prevent her recovery, actions she said caused “great suffering of body and mind.” The requested remedy? That the court issue an injunction barring him from further “mesmeric” acts. The charge bordered on the metaphysical equivalent of a restraining order—against one man’s thoughts.

The legal absurdity was not lost on the court. Presiding over the matter was Judge Horace Gray, a Harvard-educated jurist and future U.S. Supreme Court justice. On May 17—just three days after the filing—Gray dismissed the case in terse, unmistakable terms. The court, he ruled, could not adjudicate questions of unseen influence or psychic intent. However sincerely Brown believed she had been harmed, the law did not—and could not—regulate thought.

With that ruling, the last judicial proceeding in American history to echo the structure of a witchcraft trial came to an unceremonious end. No testimony, no dramatic confrontation—just the cold logic of a secular judiciary unwilling to entertain metaphysical grievance. Yet the case lingered in the public imagination. To some, it confirmed the eccentricity—if not the danger—of Christian Science. To others, it marked the final repudiation of a dark chapter in American religious persecution.

Yet one cannot help but note the irony. In 1692, it was women like Brown—accused of unseen crimes, subjected to legal sanction without material evidence—who were dragged before magistrates in Salem. In 1878, a woman stood before that same legal system, now empowered as plaintiff, invoking the very logic of psychic injury once used to condemn others. That her complaint failed is, in its own way, a testament to the triumph of Enlightenment jurisprudence. But that it was brought at all—by an educated woman in postbellum Massachusetts—suggests that the specter of invisible harm had never truly vanished from American consciousness.

Brown v. Spofford did not result in gallows or martyrdom, nor did it spark a movement. But it stands as a historical oddity: the moment when modern law collided, one last time, with the ancient fear that thoughts can kill.