On May 23, 1430, amid the brutal and grinding wars that had ravaged France for nearly a century, the woman who had once turned the tide of battle at Orléans found herself surrounded, outnumbered, and—most damning of all—abandoned. Joan of Arc, the teenage peasant-turned-warrior whose celestial visions had galvanized the French cause, was captured at the gates of Compiègne by troops allied with the Duke of Burgundy, a faction nominally French but practically subordinate to the English. Her seizure was not merely a tactical loss for Charles VII’s army. It marked the beginning of the end for one of history’s most improbable military careers, and the start of a politically expedient martyrdom that would shake both throne and church.

The Siege of Compiègne, though far less mythologized than Orléans or Reims, was a strategic flashpoint in the final decades of the Hundred Years’ War. After her triumphant campaigns in 1429, Joan’s political influence waned. The French court, wary of her popularity and increasingly inclined toward negotiated settlements with the Burgundians, had withdrawn much of its support. Joan, however, pressed on. She joined a small force attempting to defend Compiègne, a loyalist town under threat from a combined Burgundian-English force. She entered the city in early May, determined to rally the defenders. It would prove a fatal act of devotion.

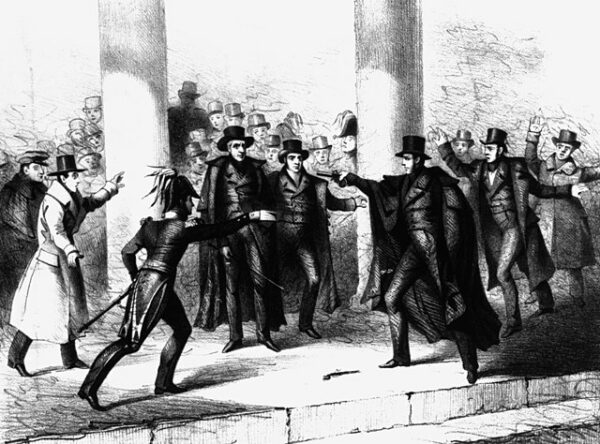

On the morning of May 23, with the city partially encircled and Burgundian forces probing its defenses, Joan led a sortie—a bold attempt to disrupt the siege lines and test enemy strength. For a time, the maneuver succeeded. The French drove the attackers back toward the woods. But the retreat was a ruse. Burgundian reinforcements, lying in wait, enveloped Joan’s position. As her forces scrambled to withdraw behind the city’s gates, the drawbridge was raised. Whether out of panic or political calculation, the defenders shut her out. Joan, still fighting on horseback, was dragged from her mount and taken prisoner.

Her captor was a Burgundian vassal, Jean de Luxembourg, who would soon recognize the enormous value of his prisoner—not just as a military figure, but as a propaganda trophy. Joan’s captors held her for months, eventually selling her to the English for 10,000 livres—a sum that underscores her symbolic weight in the Anglo-French struggle. Charles VII, the very king she had delivered to coronation at Reims, made no serious effort to ransom or rescue her. His silence was deafening.

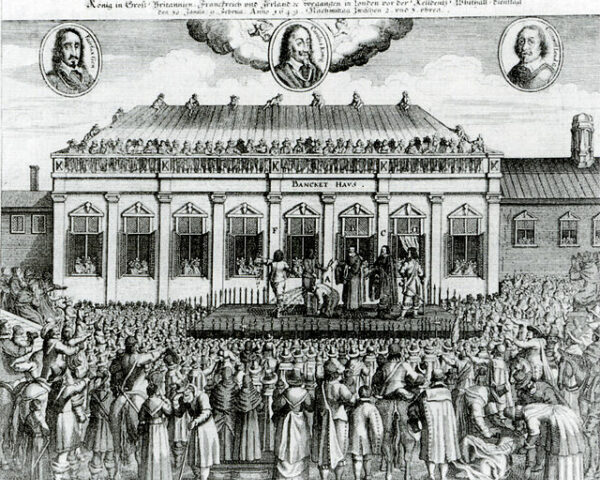

That silence—rooted in courtly politics, clerical unease, and the fragile détente with Burgundy—was a death sentence. Once in English custody, Joan would be tried in Rouen by an ecclesiastical court that masqueraded as a tribunal of conscience. But her real crime was not heresy—it was that she had embarrassed powerful men. She had dared to claim divine authority, dared to wield the sword, dared to crown a king while wearing armor. She had made herself a force beyond their control. And for that, she would be extinguished.

The capture at Compiègne was the moment when that extinguishing became inevitable. The voices she followed—the saints she claimed spoke to her—would fall silent in prison. But so too, for a time, did the spirit she had awakened in France. With Joan gone, the war slogged on for two more decades. Yet the memory of the girl who had once told her king, “I was born for this,” refused to fade.

In time, the church that condemned her would canonize her. The France that let her die would revere her as its patron saint. But on May 23, 1430, all of that lay hidden behind the iron bars of a Burgundian cage, while the woman who had defied the logic of war found herself undone not by sword or siege—but by betrayal.