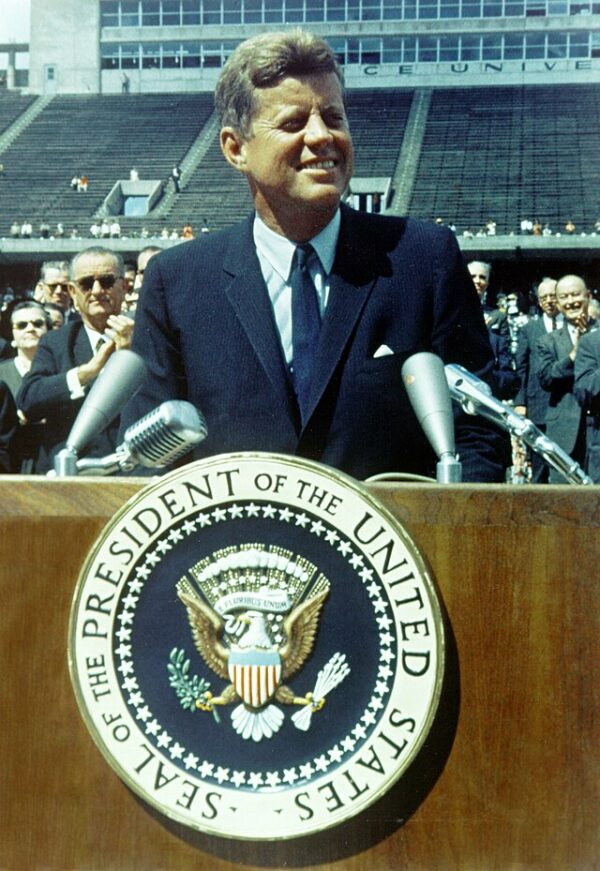

On May 25, 1961, in a bold speech delivered before a special joint session of the United States Congress, President John F. Kennedy issued a challenge that would define a generation and redirect the trajectory of American science, industry, and global prestige. Speaking just four months into his presidency, Kennedy called for the United States to commit to “achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.” It was an audacious proposal—part political gamble, part visionary leap—that would become the foundation of the Apollo program and ultimately one of the most iconic achievements in human history.

Kennedy’s speech came at a moment of profound Cold War anxiety. Less than a month earlier, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had become the first human to travel into space, orbiting the Earth aboard Vostok 1 and sending a shockwave through the American public and political establishment. The Soviet Union, already perceived as a formidable military rival, now appeared technologically superior in the arena of space exploration—a potent proxy battlefield in the ideological struggle between communism and democracy.

The American space effort had gotten off to a rocky start. The fledgling National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), established in 1958 in response to the Soviet launch of Sputnik, had just completed its first manned spaceflight with astronaut Alan Shepard’s suborbital mission aboard Freedom 7 on May 5, 1961. While Shepard’s 15-minute flight was a significant milestone, it paled in comparison to Gagarin’s orbital voyage. Kennedy and his advisers knew that symbolic parity with the Soviets would not be enough; only a bold, unambiguous victory could restore America’s technological and ideological standing on the world stage.

Kennedy’s May 25 address, formally titled “Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs,” was about more than just the Moon. It was a sweeping call to action on defense, economic policy, education, and civil defense. But it was the space program—specifically, the Moonshot—that captured imaginations and headlines. “No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind,” Kennedy declared, “or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

Indeed, it would be both. The Apollo program would eventually consume more than $25 billion in 1960s dollars (equivalent to over $250 billion today), employ hundreds of thousands of engineers, technicians, and contractors, and rely on an intricate web of universities, private industry, and federal agencies. At its peak, NASA absorbed over 4% of the federal budget—an extraordinary commitment driven not merely by scientific curiosity, but by geopolitical necessity and national pride.

Kennedy was not unaware of the costs and challenges. He acknowledged in his address that the Moon mission would require “a major national commitment of scientific and technical manpower, material and facilities, and the possibility of their diversion from other important activities where they are already thinly spread.” But he framed the effort in moral and civilizational terms, casting it as a testament to the democratic will and ingenuity of a free society.

The speech marked a turning point in both American politics and the space race. It effectively transformed NASA’s mission from one of basic research and orbital experimentation into a goal-driven, deadline-focused campaign. This vision would crystallize further in Kennedy’s September 1962 speech at Rice University, where he famously said, “We choose to go to the Moon…not because it is easy, but because it is hard.”

Though Kennedy would not live to see the fruits of his ambition—he was assassinated in 1963—the goal he set that day in 1961 would be realized on July 20, 1969, when Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the lunar surface. The successful Moon landing fulfilled the promise of Kennedy’s vision and became a defining moment of the 20th century.

In hindsight, Kennedy’s Moonshot stands as a rare confluence of political courage, scientific prowess, and national unity. It was a gamble—expensive, risky, and uncertain—but it proved that bold leadership could mobilize a democracy to accomplish the extraordinary.