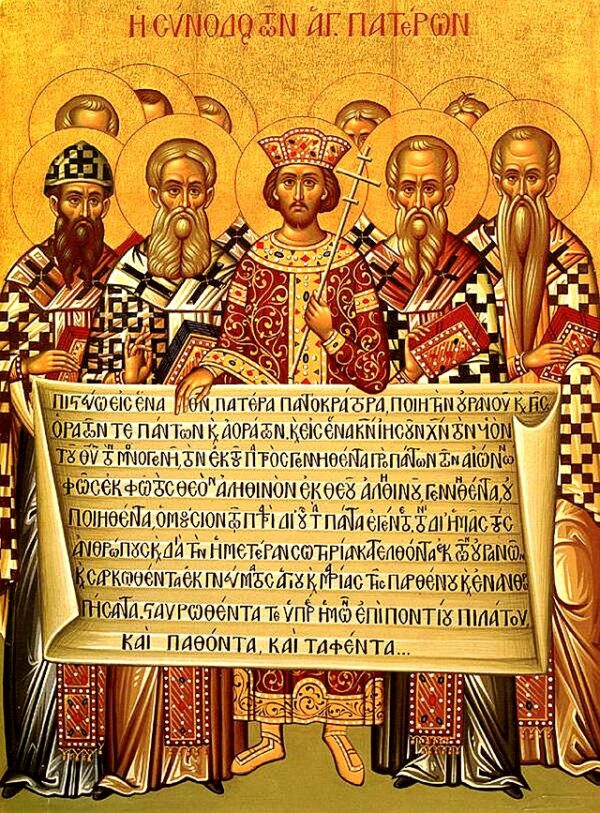

On June of 325 AD, in the lakeside city of Nicaea—then a modest but strategically situated settlement in the Roman province of Bithynia—the trajectory of Christian orthodoxy was decisively altered. What emerged from that convocation, held under the watchful eye of Emperor Constantine the Great, was not merely a resolution of ecclesiastical quarrel but a blueprint for theological authority, a declaration of dogma that would outlive the empire itself. On June 19, the assembled bishops, some three hundred strong and drawn from the breadth of the Roman world, ratified the original Nicene Creed: a bold, formulaic statement affirming the co-eternal divinity of Jesus Christ and defining, with striking philosophical precision, the nature of the Godhead. In so doing, they did not so much resolve a debate as erect a doctrinal wall—rigid, enduring, and still contested—around the core mysteries of Christian faith.

The impetus for this imperial council was less divine than political. Constantine, a canny consolidator of power, had recognized what centuries of emperors had ignored: that religious division posed a threat to imperial unity just as grave as military rebellion or economic collapse. The most volatile of these divisions was the Arian controversy, named for Arius, a presbyter from Alexandria who had dared to suggest that the Son of God—though exalted above creation—was Himself created. Christ, Arius insisted, was not homoousios (of the same essence) as the Father but homoiousios (of like essence)—a seemingly small distinction, yet one that cut to the heart of salvation itself. For if Christ was not truly divine, could He truly redeem?

To many bishops, especially those shaped by the theological legacy of Alexandria and the emerging Trinitarian orthodoxy, Arius’s claim amounted to blasphemy wrapped in syllogism. But Arius was no mere outlier; his views had spread widely, supported by influential clergy and buttressed by the imperial bureaucracy. It was to contain this doctrinal wildfire that Constantine summoned the bishops of the Christian world to Nicaea—not as a neutral observer but as a patron, a broker of peace, and, in a sense, a proto-theologian of statecraft. Constantine’s goal was not metaphysical clarity; it was unity, the old Roman ideal now dressed in Christian vestments.

What followed was a month of bitter dispute, rhetorical maneuvering, and theological brinkmanship. At issue was the most elemental question of all: Who is Christ? The answer that emerged, inscribed in Greek and proclaimed on June 19, was revolutionary in its simplicity and its force. Christ, the Creed declared, is “God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, of one essence with the Father.” The phrase homoousios—theologically radical, philosophically loaded—was inserted not to placate, but to exclude. It was a line in the sand: Arianism stood on the wrong side.

And with that formulation came exile. Arius and a handful of his supporters were anathematized and banished, their teachings condemned as heresy. Yet if the council sought finality, it failed. The Nicene Creed, far from quelling controversy, opened new fronts in a theological civil war that would rage for decades. Successive emperors would reverse course, councils would be reconvened, and orthodoxy itself would mutate in the crucible of imperial politics. But Nicaea’s act—its creedal proclamation—endured, not because it silenced dissent but because it framed the terms of every subsequent debate.

The council did more than define Christ; it began the process of defining the Church itself. Canons were issued—on the authority of bishops, on the reconciliation of the lapsed, on the scheduling of Easter. There was, notably, no New Testament canon declared, nor was Rome granted any primacy. What emerged instead was a vision of catholicity grounded not in geography but in dogma. Orthodoxy was no longer a matter of tradition or scriptural interpretation alone; it was now a matter of creed, of lines recited and boundaries drawn.

The Nicene Creed as it survives today—slightly modified in 381 at the Council of Constantinople—remains a living artifact of that imperial theology. It is chanted in Orthodox liturgies, recited in Catholic Masses, and echoed in Protestant confessions. But its authority rests not merely in its antiquity. It endures because it wrestled, with a clarity few statements ever achieve, with the central paradox of Christian faith: that the infinite became finite, that the eternal was born in time, that the man from Nazareth was—and is—very God of very God.