In the feverish days leading up to American independence, when the fate of the colonies teetered between rebellion and subjugation, the Continental Army faced not only threats from British redcoats but from within its own ranks. On June 28, 1776, Thomas Hickey—a private in the elite Life Guard assigned to protect General George Washington—was executed by hanging in New York City for mutiny and sedition. His death marked the first execution of an American soldier by the Continental Army and sent a clear message: treason would not be tolerated, even in the cradle of liberty.

Hickey’s execution was not merely a case of military discipline. It became a public spectacle, witnessed by thousands, underscoring the fragility of revolutionary unity. A former British soldier turned rebel, Hickey had joined the Continental Army and was handpicked to serve in the Commander-in-Chief’s personal guard—an appointment reserved for men deemed honorable and loyal. Yet beneath the uniform, Hickey nursed grievances and ambition. When arrested for passing counterfeit Continental currency, his misdeeds opened a window into a darker conspiracy.

While detained in a New York City jail, Hickey reportedly bragged of a wider plot to undermine the patriot cause. He and other conspirators, including suspected loyalists and disaffected soldiers, were allegedly preparing to defect to the British upon their expected arrival in New York. The supposed scheme involved inciting a mutiny, sabotaging Continental efforts, and—most shockingly—assassinating General Washington himself.

These revelations sent tremors through the colonial leadership. The plot, while never fully substantiated in all its details, struck a nerve in a city crawling with spies, informants, and wavering allegiances. New York in the summer of 1776 was a volatile staging ground for what many believed would be the decisive campaign of the war. British ships had been spotted in the harbor, and Washington’s makeshift army was bracing for a brutal showdown.

In this atmosphere of anxiety and suspicion, Hickey was brought before a court-martial. Witnesses testified to his seditious statements and disloyal conduct. Though the more dramatic allegations of a plot to kill Washington could not be proved conclusively, the charges of mutiny and sedition were sufficient. Hickey was found guilty and sentenced to death.

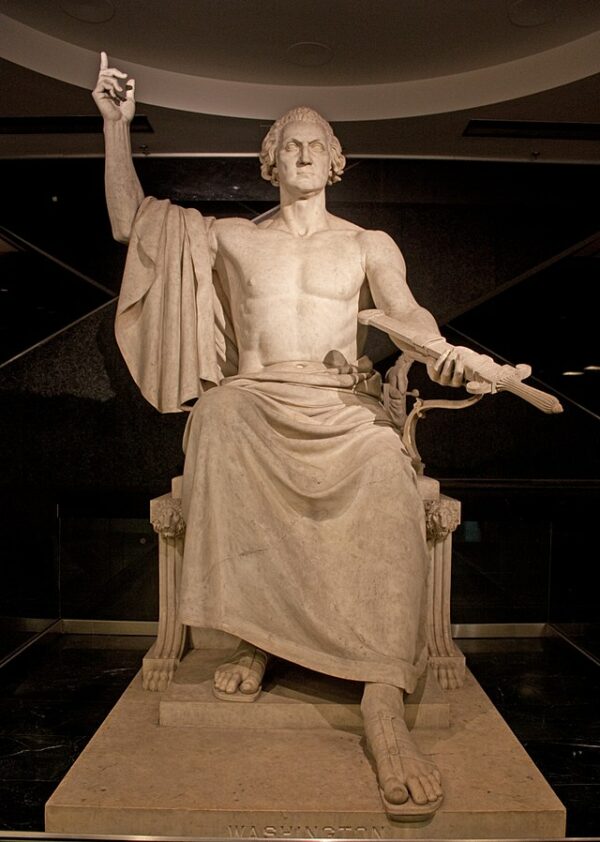

His execution on June 28 was a deliberate act of political theater. He was hanged before a massive crowd—some accounts estimate more than 20,000 onlookers—assembled not only to punish one man but to shore up the morale and discipline of the army. Washington, ever conscious of the symbolic weight of such moments, reportedly endorsed the decision to make the hanging a public affair. A general who prided himself on restraint, Washington recognized the power of example, especially in a cause held together by fragile unity and untested loyalty.

The hanging of Thomas Hickey served a dual purpose. It eliminated a threat from within and warned others tempted by British promises or embittered by poor rations and meager pay. But it also revealed the perilous uncertainties faced by the revolutionaries: not only could muskets and bayonets turn against them on the field, but treachery could fester inside their own barracks.

Whether Hickey truly plotted to kill the general or simply fell in with the wrong company while engaged in petty crime, his fate was sealed by the political needs of the moment. The army could not afford dissent, and Washington could not allow his authority—or the cause itself—to appear vulnerable. Hickey, in the end, became both scapegoat and warning.