In the minds of many Americans, July 4th is the nation’s birthday—the date celebrated with fireworks, patriotic speeches, and parades across the country. Yet it was on July 2, 1776, that the Continental Congress formally broke ties with Great Britain by adopting the Lee Resolution, a brief but momentous declaration of independence that severed the legal bonds between the thirteen American colonies and the British Crown. This act, less adorned than the eloquent prose of the Declaration of Independence adopted two days later, nonetheless marked the actual moment the United States chose revolution over reconciliation and committed itself to sovereignty.

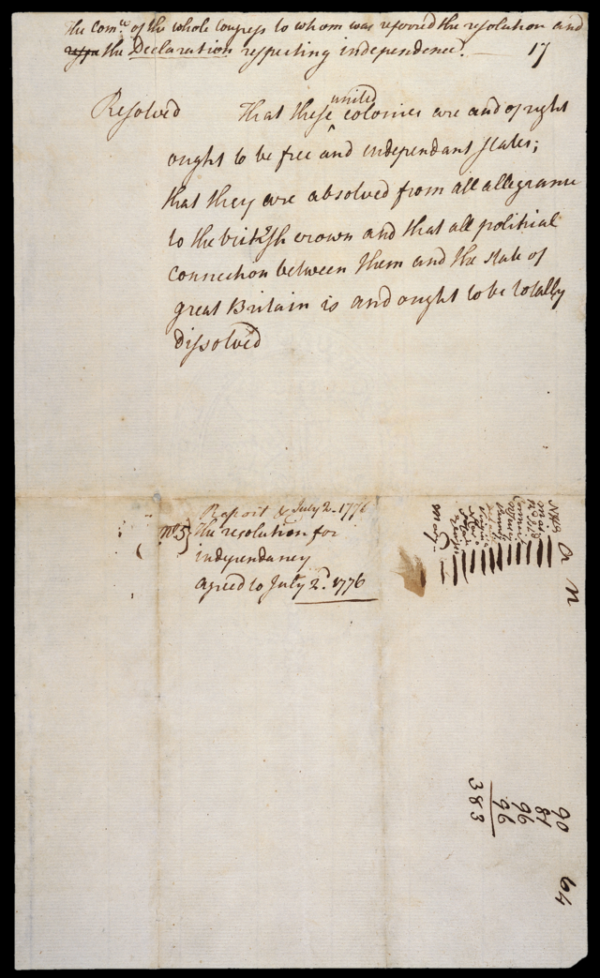

The resolution had been introduced nearly a month earlier, on June 7, by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. Backed by the Virginia Convention and long anticipated by radicals like John Adams, Lee’s proposal called for the colonies to declare themselves “free and independent States,” to dissolve all allegiance to the British monarch, and to begin the process of forging foreign alliances. His motion read simply:

“Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States; that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown…”

Though the language was concise, its implications were revolutionary. The colonies were not merely protesting taxation or British overreach—they were opting to unmake empire.

The path to the vote on July 2 was neither swift nor uncontested. While support for independence had been growing steadily since the outbreak of hostilities in 1775—especially following Thomas Paine’s galvanizing pamphlet Common Sense—many delegates remained cautious. Some feared British retaliation, others doubted the unity or capacity of the colonies to survive without imperial support. As a result, the Continental Congress appointed a “Committee of Five” (Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston) to draft a formal declaration while awaiting clearer consensus.

During the intervening weeks, the colonies hurried to instruct their delegates. One by one, colonial legislatures authorized their representatives to vote for independence. By July 1, the votes were nearly aligned. That day, after intense debate in Philadelphia’s State House (later known as Independence Hall), the Congress was nearly evenly split. Pennsylvania and South Carolina still leaned against independence, while New York’s delegates were instructed to abstain. But on the morning of July 2, South Carolina shifted its vote, Delaware’s deadlock was broken when Caesar Rodney rode through the night to cast his vote in favor, and Pennsylvania’s delegation divided, allowing the independence faction to prevail.

Thus, on July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Lee Resolution with twelve of the thirteen colonies voting in favor, and New York abstaining—not out of opposition, but because its delegates had not yet received authorization from their legislature.

John Adams, writing to his wife Abigail that night, predicted that July 2 would be remembered as the most celebrated date in American history. “The Second Day of July 1776,” he wrote, “will be the most memorable Epocha in the History of America. … It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations.”

Yet it was not July 2, but July 4—the date the Congress approved the final wording of Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence—that became enshrined in the national consciousness. While Lee’s Resolution carried the force of law and the political reality of independence, Jefferson’s text gave that decision poetry, philosophy, and a moral claim to legitimacy. The Declaration’s invocation of natural rights and its sweeping denunciation of King George III would echo through American political thought for generations.

Still, the significance of July 2 should not be overlooked. It was the day the Continental Congress declared, in a binding vote, that the colonies were no longer part of the British Empire. The later adoption of the Declaration was a necessary act of political communication—but it was July 2 that made America independent.

In that sense, the United States has two founding moments: one of substance, and one of symbolism. July 2, 1776, was the decisive break. July 4 was the explanation. Together, they forged the political and ideological foundation for a new nation—born not in harmony, but in courage, conflict, and conviction.