On July 10, 1832, President Andrew Jackson made one of the most shocking moves in American history. He vetoed legislation to re-charter the Second Bank of the United States, a moment that reverberated far beyond the immediate fate of a financial institution. The veto, issued in the heat of Jackson’s re-election campaign, symbolized a dramatic redefinition of presidential authority and a foundational confrontation between elite economic control and democratic populism. At stake was not just a bank’s charter, but the very balance between federal institutions, private capital, and the power of the executive.

The Second Bank, chartered in 1816 after the financial chaos of the War of 1812, was intended to bring order and stability to the nation’s monetary system. Modeled loosely after Alexander Hamilton’s original Bank of the United States, the institution operated as a quasi-public central bank, managing federal deposits, issuing a uniform national currency, and restraining inflation by checking state-chartered banks. But to Jackson and his supporters, it represented an undemocratic concentration of power—an engine of corruption, privilege, and political manipulation.

Jackson’s hostility toward the Bank had long simmered. He viewed it as a “monopoly” that benefited a wealthy few at the expense of ordinary citizens. The Bank’s president, Nicholas Biddle, became Jackson’s chief antagonist—a polished Philadelphian and advocate of centralized financial power, who saw the Bank as essential to national prosperity. For Biddle and many in Congress, re-chartering the Bank early (its charter was not due to expire until 1836) was a strategic move to neutralize the issue ahead of the 1832 election. For Jackson, it was a political trap and a constitutional affront.

The veto message Jackson issued was sweeping and incendiary. He denounced the Bank as unconstitutional—notwithstanding the Supreme Court’s earlier ruling in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) that upheld its legality. More radically, Jackson argued that each branch of government had the right to interpret the Constitution independently. In rejecting the Court’s authority, Jackson reasserted the president’s role as the “direct representative of the American people,” positioning himself not merely as the executor of Congress’s will, but as the people’s champion against entrenched interests.

Jackson’s veto rested on three broad arguments: first, that the Bank concentrated economic power in a private institution unaccountable to the people; second, that it privileged foreign stockholders and wealthy elites over American laborers and farmers; and third, that it posed a threat to liberty by potentially influencing elections and public opinion through its control of credit and currency. “It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes,” Jackson wrote, casting the veto as an act of democratic defense.

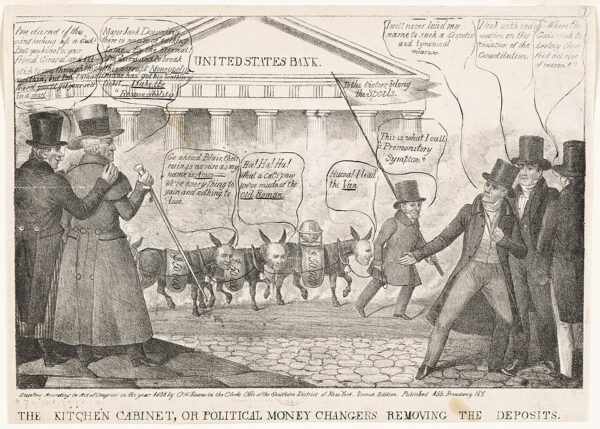

The political consequences were immediate. Henry Clay, Jackson’s opponent in the 1832 presidential race and a staunch defender of the Bank, made the veto a central issue of the campaign. But Jackson’s populist appeal prevailed: he won re-election in a landslide, interpreting the result as a mandate to dismantle the Bank entirely. In 1833, he ordered the withdrawal of federal deposits from the Bank—a legally dubious move that triggered a series of economic disruptions but solidified Jackson’s authority and marked the beginning of what became known as the “Bank War.”