On July 22, 1833, the British House of Commons passed the Slavery Abolition Act, marking a historic turning point in the British Empire’s long entanglement with slavery. Though imperfect and cautious in scope, the Act initiated the gradual dismantling of an institution that had underpinned British colonial economies for centuries—most notably in the West Indies—while also reflecting a seismic shift in moral, religious, and political thought throughout Britain.

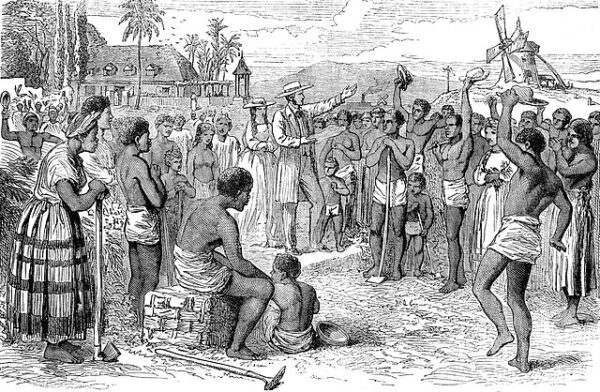

The passage of the Act did not occur in a vacuum. It was the culmination of decades of tireless activism by abolitionists such as Thomas Clarkson, Granville Sharp, and William Wilberforce. These figures had spent years campaigning against the transatlantic slave trade, which Parliament had outlawed in 1807. Yet abolition of the trade had not meant abolition of slavery itself. Enslaved men, women, and children continued to toil in the sugar fields of Jamaica, Barbados, and other colonies, their labor essential to the profitability of British commerce. What changed by the early 1830s was not only public sentiment but also political calculation, economic transition, and the increasing threat of rebellion in the colonies.

The Caribbean, where slavery was most entrenched, had seen repeated uprisings—most recently the Baptist War in Jamaica (1831–1832), in which tens of thousands of enslaved people revolted. Though suppressed, the uprising shook British confidence in the sustainability of slavery. The cost of maintaining order through military force and surveillance was rising, while the moral cost had already grown too high for many Britons, particularly Evangelical Christians and members of the growing working-class reform movement. The Reform Act of 1832, which expanded the electorate, helped usher in a Parliament more receptive to abolitionist arguments.

The Slavery Abolition Act passed the Commons on July 22 and received royal assent on August 28, 1833. It took effect on August 1, 1834. Its provisions were sweeping but flawed. Slavery was to be abolished across most of the British Empire, including the Caribbean, South Africa, and Canada. However, several significant exceptions and compromises tempered its impact. First, the Act did not apply to territories held by the East India Company or to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and St. Helena until 1843. Second, and more controversially, the Act instituted a system of “apprenticeship” for enslaved people over the age of six. They would be required to work unpaid for their former masters for up to six years (later reduced to four) before gaining full emancipation. This system was widely criticized as a continuation of slavery under another name.

Perhaps most egregiously, the Act included a massive compensation scheme—not for the formerly enslaved, but for their owners. The British government allocated £20 million (equivalent to billions today), roughly 40% of the national budget, to reimburse slaveholders for their “loss of property.” This payment solidified existing hierarchies of wealth and left the emancipated with nothing: no land, no restitution, and little opportunity beyond plantation labor.

Still, despite its limitations, the Slavery Abolition Act was revolutionary. It made the British Empire the first major European power to legally dismantle slavery across a vast global territory. In time, the legislation inspired abolitionist movements in France, the United States, and Brazil. More immediately, it changed the moral language of empire, allowing Britain to present itself as a civilizing force, even as it continued to exploit colonial labor and maintain imperial dominance.