On August 2, 1939, just weeks before the outbreak of World War II, physicist Albert Einstein and fellow Hungarian émigré Leo Szilard co-signed a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt that would become one of the most consequential pieces of correspondence in history. The letter warned that Nazi Germany might be attempting to develop a powerful new type of bomb—based on recent discoveries in nuclear fission—and urged the United States to begin similar research. Their plea led directly to the creation of the Advisory Committee on Uranium and ultimately paved the way for the Manhattan Project, the top-secret American endeavor to build the world’s first nuclear weapons.

The background to the letter was scientific as well as geopolitical. In 1938, German physicists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann, followed by Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch, discovered that uranium atoms could be split into smaller parts, releasing tremendous amounts of energy in a process called nuclear fission. The discovery suggested that it might be possible to build an immensely powerful weapon—something far beyond any existing explosive.

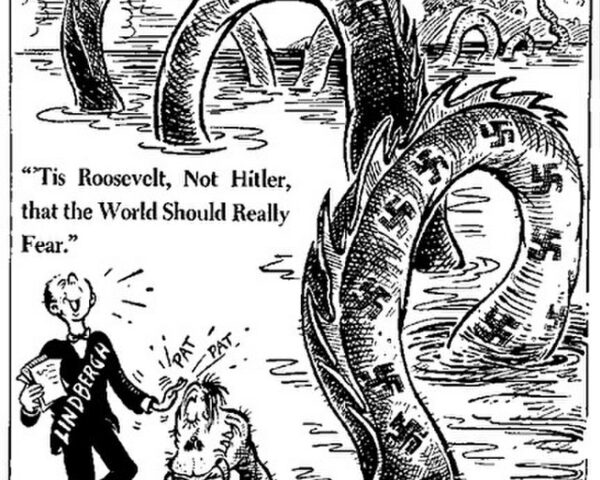

Szilard, a physicist who had fled fascist Europe and who had long speculated about chain reactions and their implications, quickly grasped the terrifying potential. With the help of fellow émigré scientists like Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner, Szilard recognized the danger that Nazi Germany, already home to many leading physicists, could weaponize uranium. He was particularly alarmed by Germany’s seizure of Czechoslovakia’s uranium mines and its ban on the export of uranium ore.

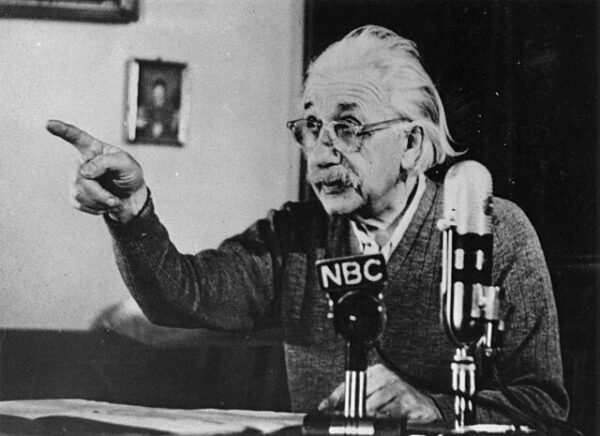

Szilard believed the United States government had to be warned, and that Einstein—perhaps the most famous scientist in the world—would be the most persuasive messenger. Though not closely involved in nuclear physics at the time, Einstein lent his name and reputation to Szilard’s cause. Together, they drafted a letter in which Einstein outlined the potential for an “extremely powerful bomb of a new type” and suggested that “a single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory.”

Delivered to Roosevelt by economist Alexander Sachs in October (after delays caused by the outbreak of war in Europe), the letter made a powerful impression. FDR quickly authorized the creation of a committee to investigate the feasibility of uranium-based weapons. Although the U.S. government initially allocated only modest funding and proceeded cautiously, the effort accelerated dramatically after the United States entered the war in 1941.

The Manhattan Project—named for the Army Corps of Engineers district that first managed the effort—grew into one of the largest and most secretive military-industrial enterprises in history. It brought together thousands of scientists, engineers, and workers across sites in Los Alamos, New Mexico; Oak Ridge, Tennessee; and Hanford, Washington. The project ultimately produced two types of atomic bombs: one using uranium-235 (“Little Boy”) and the other using plutonium-239 (“Fat Man”).

On July 16, 1945, the first successful test of an atomic bomb—code-named “Trinity”—was conducted in the New Mexico desert. Less than a month later, the weapons were dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, leading to Japan’s surrender and the end of World War II. The devastation caused by the bombings ushered in the nuclear age and dramatically altered the course of global history.

Einstein later expressed regret over his role, stating, “Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in developing an atomic bomb, I would have done nothing.” Yet the letter he co-signed with Szilard remains a pivotal moment in the 20th century: a warning born of scientific insight and moral urgency that set in motion a chain of events culminating in the most fearsome weapon humanity has ever known. August 2, 1939, thus stands as the date when science and statecraft first converged in the nuclear era.