On August 12, 1676, in the swampy woodlands near Mount Hope in present-day Bristol, Rhode Island, the Wampanoag sachem Metacomet—known to the English as “King Philip”—was shot and killed by an Indigenous ally of the English named John Alderman. The single musket ball ended the life of a man who had led one of the most destructive wars in early American history and brought the conflict known as King Philip’s War to a decisive close.

The war’s roots stretched back decades. In 1620, the Pilgrims landed in Wampanoag territory, and for a time relations were pragmatic, even friendly, as Metacomet’s father, Massasoit, forged alliances to protect his people against rival tribes. But as English settlements multiplied in the 1630s–50s, Native lands were sold, seized, or lost through debt, and colonial laws increasingly undercut tribal sovereignty. Metacomet inherited leadership in 1662 after Massasoit’s death and his brother Wamsutta’s suspicious demise following questioning by Plymouth officials. By then, distrust had hardened on both sides.

The immediate spark for war came in 1675, when a Christian Indian named John Sassamon warned Plymouth authorities that Metacomet was preparing for war. Sassamon’s body was soon found under the ice of a pond. The English tried and executed three of Philip’s men for his murder—an act Philip saw as an affront to Wampanoag authority. Raids and counter-raids spiraled into full-scale war, drawing in the Narragansett, Nipmuc, and other tribes against the English colonies of Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, and Connecticut.

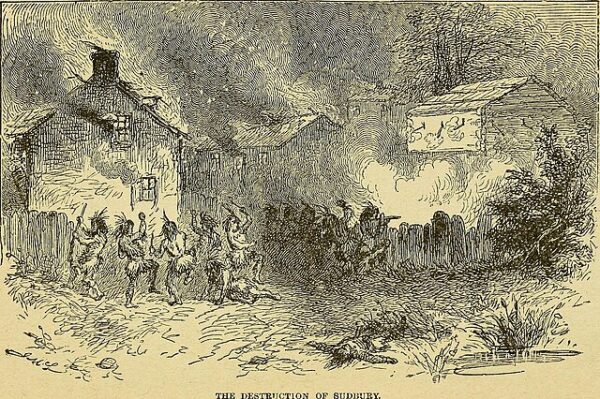

For much of 1675, Native forces enjoyed startling success, destroying towns from the Connecticut River Valley to the edges of Boston. The English responded with a brutal winter campaign, most infamously the Great Swamp Fight in December, which killed hundreds of Narragansetts and destroyed their stronghold. By early 1676, famine, disease, and the defection of Native allies had weakened Philip’s coalition. Colonial militias, guided by Native scouts who knew the terrain, hunted the remaining resistance bands relentlessly.

John Alderman, a Christian Indian and former subject of Philip, was one such scout. Colonial sources say Alderman’s loyalty shifted after Philip executed his brother on suspicion of treachery—a killing that may have been personal as much as political. By the summer of 1676, Alderman was serving under Captain Benjamin Church, a colonial officer whose blend of English weaponry and Native tactics proved decisive in the war’s final months.

On August 12, Church’s force learned from informants that Philip was hiding near Mount Hope, his ancestral seat. At dawn, they encircled the swamp. As Philip emerged, Alderman fired the fatal shot, striking him through the heart. Another colonial soldier fired at nearly the same moment, but most accounts credit Alderman with the kill. Philip fell face-first into the mud, ending his campaign of resistance.

The English exacted a grim vengeance. Philip’s body was beheaded and quartered; his head was sent to Plymouth and displayed on a pike for two decades. His hands were given to Alderman, who preserved and exhibited them, collecting a bounty for his service.

Philip’s death shattered Native resistance in southern New England. While fighting lingered in northern New England until 1678, the southern theater of the war was over. The human cost was staggering. It is estimated that a greater proportion of New England’s population died in King Philip’s War than in any other American conflict, including the Civil War. Dozens of towns lay in ruins. Thousands of Native people were killed, enslaved, or forced into exile in the West Indies.

For the English, the war’s end brought relief but also a recognition of vulnerability. The colonies had nearly been destroyed, and rebuilding took years. For Native peoples, it marked the collapse of political autonomy in the region. Surviving Wampanoags, Narragansetts, and Nipmucs lived under colonial authority, their lands absorbed into English farms and towns.

John Alderman’s legacy is ambiguous. In colonial records, he is celebrated as the man who felled “King Philip.” In Native memory, his role reflects the divisions, survival strategies, and personal vendettas that war forced upon Indigenous people. His shot on that August morning was not only the death of a war chief but the symbolic end of an Indigenous-led bid to halt the English tide—a tide that would not recede.