On August 17, 1585, a company of English settlers, dispatched under the authority of Sir Walter Raleigh and commanded by Ralph Lane, made landfall on Roanoke Island—just off the coast of what is now North Carolina. This moment marked the founding of England’s first sustained colonial effort in North America, a project steeped in high ambition, perilous uncertainty, and the geopolitical rivalries of Elizabethan Europe.

Raleigh, who had received his patent for colonization from Queen Elizabeth I in 1584, envisioned Roanoke as a strategic outpost. Its location, nestled within the barrier islands of the Outer Banks, was considered ideal for privateering against Spanish treasure fleets while simultaneously serving as a base for future expansion into the continent. To carry out the plan, Raleigh appointed Sir Richard Grenville as admiral of the fleet. However, it was Ralph Lane, a soldier and veteran of Ireland’s brutal wars, who would assume command of the colony itself once established.

The fleet that brought Lane’s colonists across the Atlantic was substantial: seven ships bearing more than one hundred men, including soldiers, craftsmen, and scientists such as the mathematician Thomas Harriot and the artist John White. Their task was not merely to endure but to reconnoiter, document, and prepare the way for permanent settlement. White’s watercolors of local flora, fauna, and Algonquian peoples remain among the most vivid legacies of the venture, offering a rare glimpse of coastal Carolina in the late sixteenth century.

Arrival, however, did not mean triumph. The colonists discovered quickly that Roanoke was an inhospitable choice. The sandy soil was ill-suited for crops, and the barrier island geography left the settlement exposed to storms and cut off from reliable fresh water. Worse, relations with the indigenous Algonquian tribes, initially friendly, soured rapidly. The English depended heavily on native communities for food and knowledge of the land, yet mutual suspicion—exacerbated by the colonists’ demands and occasional violence—strained ties to the breaking point. By autumn of 1585, hostility had replaced cooperation, and Lane’s men increasingly resorted to raids to secure provisions.

Compounding these difficulties was the colony’s fragile logistical situation. The expectation of regular resupply from England was undermined by distance, weather, and the ongoing war with Spain. Grenville returned to England shortly after delivering the settlers, promising to return the following year with reinforcements and supplies. In his absence, Lane’s leadership was tested. The garrison mentality he imposed—fortifications, strict discipline, and military patrols—kept the colony intact but deepened resentment among both settlers and native groups.

Still, the Roanoke enterprise had undeniable significance. It embodied England’s determination to contest Spain’s dominance in the New World and laid the groundwork for future colonization efforts. The colony became, in effect, an experiment—a testing ground where the English began to learn, painfully, what survival across the Atlantic entailed. Harriot’s observations on natural resources, published later in his A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, testified to the abundance of the land and reinforced the idea that America could be England’s future breadbasket, if only the logistical and human challenges could be mastered.

The fate of Lane’s Roanoke colony was sealed within a year. Besieged by hostile natives, weakened by hunger, and cut off from supplies, the settlers faced collapse. When Sir Francis Drake’s fleet appeared off the coast in June 1586, returning from successful raids in the Caribbean, Lane accepted rescue. The colonists abandoned Roanoke and sailed back to England, carrying with them samples of tobacco, maize, and potatoes—crops that would transform European diets and economies.

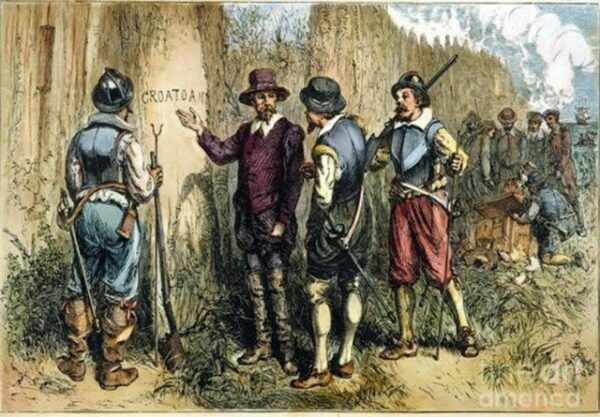

Yet the dream of Roanoke did not end with Lane’s departure. Grenville arrived shortly after with reinforcements, found the settlement deserted, and left a token garrison. In 1587, John White would lead a second, larger colony, including women and children, in a renewed attempt at permanence. That effort would become enshrined in American memory as the “Lost Colony,” its disappearance still one of history’s enduring mysteries.