On August 24, 1857, the United States was jolted into one of the most severe economic crises of the 19th century. Known as the Panic of 1857, the crash reverberated across the Atlantic, exposing the fragility of a rapidly expanding economy bound to global markets. Unlike earlier panics, which had been largely domestic in scope, this financial disaster underscored the United States’ growing entanglement with European finance and the risks of overextension in both banking and industry.

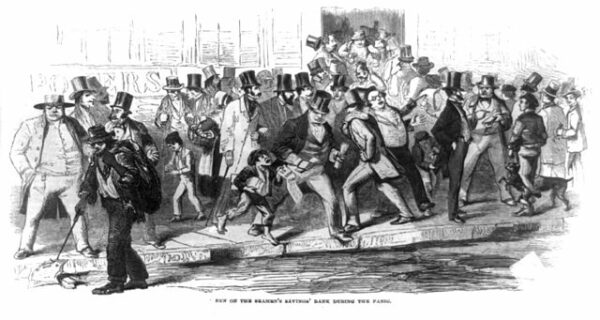

The spark came from the unexpected failure of the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company, a prominent Cincinnati-based firm with offices in New York. On August 24, news spread that its New York branch had collapsed due to massive embezzlement and reckless speculation. The revelation shattered public confidence. Bank depositors rushed to withdraw their savings, merchants scrambled to liquidate assets, and the stock market—already uneasy after a year of uneven trade—spiraled downward. Within weeks, panic coursed through every sector of the economy.

The roots of the crisis ran far deeper than a single firm’s collapse. In the preceding decade, the United States had been transformed by the California Gold Rush, the construction of railroads, and the expansion of grain exports to Europe during the Crimean War (1853–1856). Flush with gold and foreign demand, banks and investors poured money into speculative ventures, particularly railroads, which promised to knit the vast interior of the nation into profitable markets. By 1857, however, the European demand that had buoyed American exports receded, leaving farmers and merchants overstocked with goods and railroads saddled with debt. The failure of Ohio Life was merely the first stone to fall in a crumbling financial edifice.

The contagion spread quickly. By September, the New York stock market had lost nearly half its value. Banks across the Midwest suspended specie payments—refusing to redeem banknotes for gold or silver—while factories in northern cities shuttered. The downturn was especially brutal in industrial centers dependent on wage labor. Unemployment surged in places like New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, as demand for manufactured goods collapsed. Laborers who had once benefited from the boom now found themselves idle, hungry, and increasingly restive.

Agriculture also suffered. With European markets shrinking and credit drying up, the price of wheat plummeted. Farmers in the Midwest, who had borrowed heavily to expand their acreage or invest in new machinery, faced foreclosure. Railroads that depended on grain shipments for revenue collapsed in turn. The South, however, fared somewhat better—at least in the short term. Cotton prices remained relatively stable, reinforcing the belief among slaveholders that their “King Cotton” economy was uniquely resilient. Southern politicians seized on the panic to argue that the North’s free-labor system was unstable, while slavery provided the bedrock of prosperity.

The political ramifications were profound. The Panic of 1857 deepened sectional tensions in the years leading up to the Civil War. Northern workers and farmers blamed bankers and railroad speculators, demanding reforms to limit financial risk. Southerners pointed to the resilience of cotton as proof of slavery’s superiority, sharpening ideological divisions. In Illinois, a rising lawyer named Abraham Lincoln remarked that the crisis had revealed the vulnerability of a nation dependent on speculation rather than productive labor. For Lincoln and other Republicans, the panic underscored the dangers of an economy skewed by slavery and reckless finance.

Recovery came slowly. By 1859, gold discoveries in Colorado and renewed European demand began to revive the economy, but scars remained. Thousands of businesses never reopened, and entire communities were reshaped by the wave of bankruptcies and foreclosures. More importantly, the panic had altered the political conversation. Economic collapse had not softened sectional hostilities but hardened them, giving slaveholders new confidence in their system while driving Northerners toward demands for free labor and industrial protection.

Historians today regard the Panic of 1857 as a watershed in American financial history. It was the first truly global economic crisis, linking the United States to fluctuations in European markets with devastating consequences. It exposed the volatility of a modernizing economy, the fragility of speculative finance, and the widening fault lines between North and South. Most of all, it revealed how quickly prosperity could give way to collapse, leaving behind disillusionment and a sense of foreboding.

On August 24, 1857, when the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company failed, few could have foreseen how swiftly panic would engulf the nation