For nearly two years the men of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition had been reduced to shadows of themselves, marooned at the frozen edge of the world. Their ship, Endurance, had been trapped and crushed by the pack ice of the Weddell Sea in late 1915, leaving Ernest Shackleton and his crew to make a desperate bid for survival. They trekked across shifting floes, rowed open boats through gale-swept seas, and at last scraped ashore on a barren spit of rock called Elephant Island. There they built makeshift shelters from upturned boats and scraps of canvas, and waited, uncertain whether they would ever be seen again.

For Shackleton, the loss of the Endurance meant the collapse of his grand plan to cross the Antarctic continent from sea to sea. But it did not shake his determination to preserve the lives of his men. He became determined to do something, even if it cost him his life. That something was a voyage so audacious it borders on the mythic: an 800-mile crossing of the Southern Ocean in a 22-foot lifeboat, the James Caird, with only a sextant and dead reckoning to guide them. Shackleton, Frank Worsley, Tom Crean, and three others battled monstrous seas, freezing spray, and the near-certainty of drowning as they steered northward toward South Georgia, the whaling station that represented their only hope of rescue.

They arrived half-dead, frostbitten, and skeletal. But Shackleton did not rest. After recovering strength, he and two companions staggered across the unmapped mountains and glaciers of South Georgia on foot—another feat thought impossible. When they burst into the whaling station at Stromness on May 20, 1916, they looked like ghosts, but their first thought was not of themselves. Shackleton’s only question: could a ship be found to save the men left behind on Elephant Island?

That question would haunt him for months. Three separate attempts were beaten back by ice, each failure gnawing at him. On Elephant Island, meanwhile, the men clung to existence under the leadership of Frank Wild, who each morning urged them to pack their belongings, insisting that “Shackleton will come today.” They endured frostbite, gangrene, and the slow wasting of hunger. Yet morale, fragile as it was, survived on faith in their commander’s return.

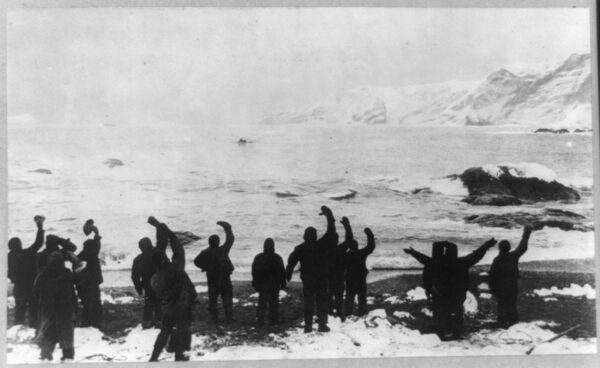

At last, on August 30, 1916, Shackleton succeeded. With the assistance of the Chilean government, he secured the small seagoing tug Yelcho, captained by Luis Pardo, and forced a path through the pack ice once more. This time the seas relented. Through the mist the outline of the rocky island came into view. As the men spotted the vessel offshore, a ragged cheer went up. Shackleton lowered a boat, sprang ashore, and counted heads. All twenty-two were alive. Not one had been lost.

The rescue was a logistical triumph. Shackleton had promised that he would not leave a man behind, and he kept that promise against all odds. The world, already engulfed in the carnage of the Great War, took notice. Newspapers hailed him as the exemplar of courage and endurance, though Shackleton himself deflected praise. He spoke only of his men, of their loyalty and perseverance, and of the relief that his gamble had not cost them their lives.