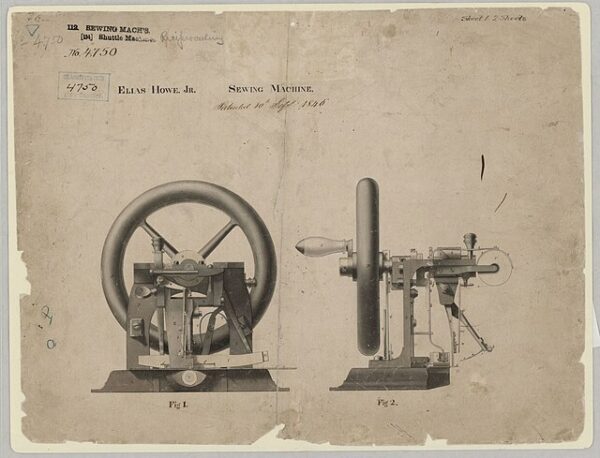

When Elias Howe secured his sewing machine patent on September 10, 1846, he likely could not have imagined the waves of industrial transformation his invention would set in motion. The 27-year-old Massachusetts mechanic had spent years tinkering in obscurity, driven by a vision of mechanizing one of humanity’s most time-consuming labors: stitching fabric by hand. What emerged from his workshop was not the first attempt at mechanical sewing, but it was the first design to combine precision, durability, and practicality in a way that would change both households and factories across the modern world.

At the heart of Howe’s device lay two crucial innovations. First was the lockstitch mechanism: a sharp, eye-pointed needle pushed thread through fabric, where a shuttle underneath interlocked it with a second thread, producing a tight, resilient seam. Second was the consistent use of a grooved needle moving on a straight path, in contrast to earlier clumsy contraptions that relied on twisting or curved needles prone to failure. With these improvements, Howe’s machine could produce as many as 250 stitches per minute—a breathtaking advance at a time when the average seamstress might complete no more than 40 hand stitches in the same span.

Yet the patent did not guarantee fame or fortune. Indeed, Howe’s life after 1846 reveals the familiar paradox of nineteenth-century American inventors: the brilliance of discovery often collided with the harsh realities of commercialization. Howe attempted to promote his machine in England, pawning his wife’s possessions to fund the journey. He found little success there and returned nearly destitute to the United States, only to discover that others—most notably Isaac Merritt Singer and Walter Hunt—had begun marketing rival sewing machines that incorporated key features strikingly similar to his.

The ensuing legal battles consumed the next decade. Howe, often portrayed as more craftsman than businessman, nevertheless proved dogged in defending his rights. His lawsuits culminated in landmark rulings that upheld his patent and forced competitors to pay royalties. By the mid-1850s, Howe was collecting licensing fees from nearly every machine sold in the country, transforming him from a struggling mechanic into a wealthy man. These cases also helped establish the legal framework of American patent protection, underscoring the broader national commitment to rewarding invention in an age of rapid industrial growth.

Beyond courtrooms and contracts, the sewing machine altered the fabric of daily life. In workshops, it dramatically increased the productivity of garment makers, spurring the rise of the ready-made clothing industry and turning cities like New York into manufacturing hubs. In homes, it gradually became a fixture of middle-class domesticity, reducing the drudgery of sewing and reshaping gendered divisions of labor. Women, long confined to hours of painstaking handwork, now had access to a machine that multiplied their output and opened new avenues for wage labor.

The sewing machine also carried symbolic weight. To admirers, it embodied the genius of Yankee ingenuity, demonstrating how practical mechanics could rival the scientific revolutions of Europe. To critics, it epitomized the unsettling pace of mechanization, threatening traditional crafts and raising anxieties about unemployment.

Howe did not live to see the full consequences of his invention. He died in 1867, just 48 years old, honored but overshadowed by more commercially adept rivals like Singer, whose brand would dominate global markets. Yet historians have consistently restored Howe’s reputation as the man who perfected the fundamental design upon which all subsequent machines rested. His 1846 patent, though contested and often copied, marked the decisive moment when mechanical sewing shifted from speculative tinkering to practical reality.