On September 11, 1776, in the brief lull following the Battle of Long Island, a small boat ferried three American delegates across the waters of New York Harbor. Their mission was audacious, if not quixotic: to test whether a negotiated peace with Britain might forestall the widening conflict that had erupted into full-scale war only the previous year. What followed on Staten Island was a short, polite, but ultimately fruitless meeting that revealed the gulf between the empire and its rebellious colonies.

The conference was convened at the behest of Admiral Lord Richard Howe, who had been dispatched to America with broad military authority and some limited power to negotiate. His fleet and army had already secured Long Island, threatening New York City itself. Yet Howe hoped that conciliation might succeed where musket fire could not. He invited representatives of the Continental Congress to meet him in the hopes of finding common ground.

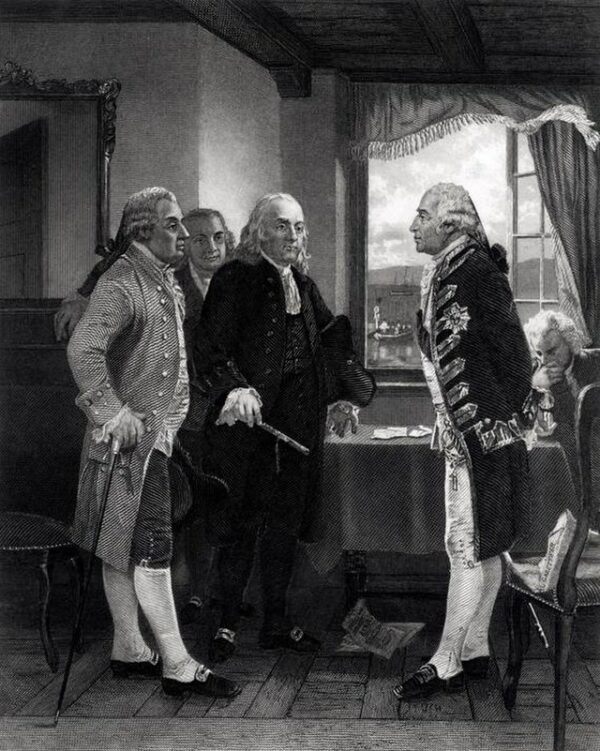

Congress, wary but eager to demonstrate reasonableness before the world, appointed three of its most capable men: John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, and Edward Rutledge of South Carolina. Their selection was strategic—Adams the fiery advocate of independence, Franklin the elder statesman of immense diplomatic prestige, and Rutledge the youngest delegate, meant to signal that even moderates among the colonies were represented.

When the Americans arrived at the Billopp House on Staten Island, the scene was cordial. Howe received them with courtesy, and the men reportedly dined together. But the genial atmosphere could not disguise the impasse that soon emerged. Howe’s instructions from London allowed him to offer pardons and to discuss grievances, but only if the colonies first acknowledged the authority of the Crown. The Americans, by contrast, had just two months earlier declared independence, proclaiming that “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states.” For them, there could be no talk of reconciliation unless Britain recognized that independence.

Adams, who had little faith in the prospect of peace, later remarked that the conference “appeared to me a meet for neither more nor less than this—whether America should be independent, or not.” Franklin, always more diplomatic, noted that Howe seemed sincere but was fatally constrained. Rutledge, though more conciliatory, could not persuade his colleagues to soften the central demand. Howe, for his part, lamented that he lacked the authority to treat with them as representatives of independent nations. Without that recognition, the Americans refused to bend.

The meeting lasted only three hours. By its end, both sides understood that no reconciliation was possible under existing terms. The delegates returned to the mainland, and Howe prepared his forces for the next phase of the campaign. Within days, British troops would occupy New York City, and the war would grind on for nearly seven more years.

The Staten Island Peace Conference has often been remembered as a moment of fleeting possibility—a juncture when bloodshed might have been averted. Yet in truth, the structural realities left little room for compromise. Britain could not concede independence without destroying its own imperial authority, and the Americans, having publicly severed ties, could not retreat without shattering their own fragile unity. The polite exchanges over dinner masked the inescapable fact that one side was fighting for reconciliation and the other for nationhood.

Historians have since seen in the failed conference the clarity of the American position by late 1776. The Revolution was no longer a dispute over taxation or representation, but a struggle for sovereignty itself. The inability of Howe and the congressional delegates to find common ground reflected more than the limits of diplomacy; it revealed the irreconcilable aims of empire and independence.