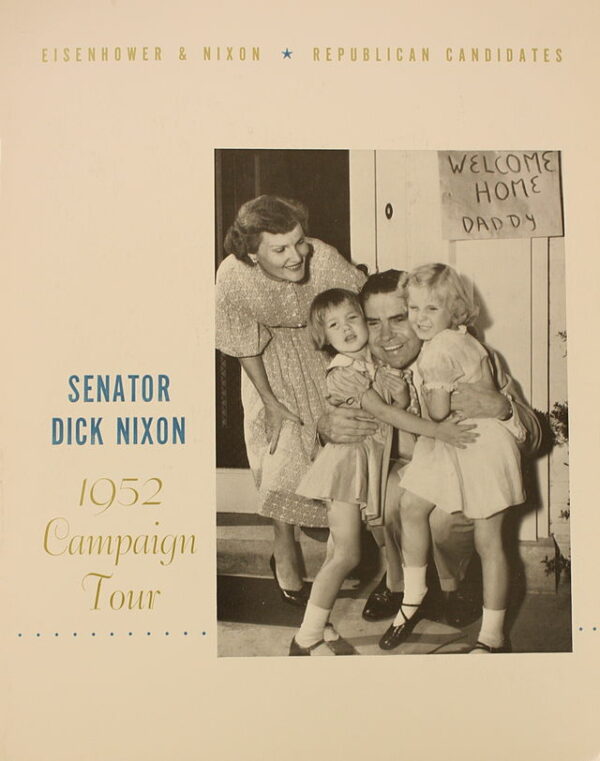

In the autumn of 1952, a young California senator named Richard Nixon faced a political crisis that might have ended his career before it truly began. Selected just weeks earlier by General Dwight D. Eisenhower as his running mate on the Republican ticket, Nixon had been accused of maintaining a private fund, contributed by wealthy California businessmen, which allegedly covered his political expenses. Critics charged that such an arrangement amounted to corruption, making him unfit for the vice presidency. Amid a rising chorus of demands for his resignation, Nixon turned to the most novel political weapon of the postwar age: television.

On the evening of September 23, 1952, Nixon delivered a nationally broadcast address—simultaneously aired on radio—that became known as the “Checkers speech.” Speaking from a Los Angeles studio, he faced not a partisan crowd but the invisible mass of the American electorate, then still adjusting to the intimacy of television politics. Nixon framed his remarks not as a cold defense of bookkeeping but as an emotional appeal, blending personal biography, populist indignation, and calculated transparency.

He began by acknowledging the charges, then launched into a meticulous explanation of his finances. Line by line, Nixon laid out his modest Senate salary, his mortgage debts, and the savings he and his wife, Pat, had managed to set aside. The much-discussed fund, he insisted, was neither secret nor corrupt: it was used exclusively to reimburse him for political travel and postage, sparing the taxpayer the burden. “Not one cent,” he declared, “of the fund has gone to my personal use.”

Yet what turned the speech from an accountancy exercise into political theater was Nixon’s rhetorical pivot to class and character. He contrasted his family’s humble lifestyle with the wealth of Democratic opponent Adlai Stevenson, who had inherited significant property. Pat, Nixon noted, did not own a mink coat, the emblem of Washington privilege, but instead wore “a respectable Republican cloth coat.” It was in this vein that Nixon introduced the line that gave the address its enduring name. The Nixons, he explained, had received one gift they would not return: a black-and-white cocker spaniel given to his daughters. “And you know,” Nixon added, “the kids, like all kids, love the dog, and I just want to say this right now, that regardless of what they say about it, we’re gonna keep it.” The dog’s name was Checkers.

By weaving together domestic imagery with indignation at elite double standards, Nixon succeeded in reframing the controversy. Instead of appearing as a grasping politician, he emerged as a beleaguered family man under unfair attack. Millions of viewers—an audience unprecedented in scale for a political broadcast—responded sympathetically. The Republican National Committee received a flood of telegrams and phone calls urging Eisenhower to keep Nixon on the ticket. The gambit worked: the next day Eisenhower announced that Nixon would remain his running mate.

The “Checkers speech” was a watershed in American politics for several reasons. It marked one of the first times a national candidate used television not merely to be seen but to rescue a career by shaping public perception directly, bypassing traditional party elites and newspaper editors. It also showcased Nixon’s political style: combative yet self-pitying, methodical yet theatrical, appealing to middle-class sensibilities while casting opponents as out of touch. The performance foreshadowed the television-driven campaigns of the later twentieth century, from John F. Kennedy’s telegenic debates to Ronald Reagan’s mastery of televised address.

For Nixon personally, the speech was both salvation and foreshadowing. He secured his place on the ticket, and Eisenhower’s decisive victory that November vaulted him into the vice presidency. Yet the episode also cemented an image of Nixon as simultaneously resourceful and embattled, a politician always fighting against accusation and suspicion. The same instinct for direct appeal to the public would resurface in later crises, most fatefully during Watergate two decades later.

Still, in 1952 the moment was triumphant. A senator on the verge of disgrace had turned adversity into opportunity, proving the power of television as a tool of political survival. And thanks to a family dog named Checkers, Nixon had written himself into the lexicon of American political history.