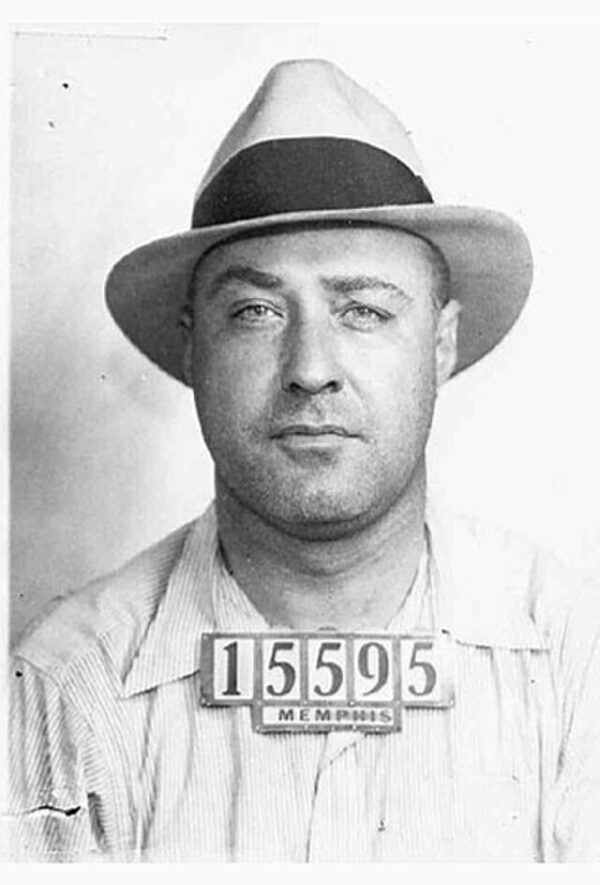

On this day in 1933, George “Machine Gun” Kelly, one of America’s most notorious gangsters, surrendered to federal agents in Memphis and gave the FBI its enduring nickname. Surrounded and with no way out, Kelly raised his hands and cried: “Don’t shoot, G-Men!” The phrase—short for “government men”—instantly entered the national lexicon, transforming into the proud label agents still carry.

Kelly’s capture came just months after the brazen kidnapping of Oklahoma oilman Charles Urschel. The gang demanded and received $200,000, but Urschel’s sharp memory of his captivity—the sounds, the smells, the habits of his guards—provided investigators with a trail. Under the newly enacted Lindbergh Law, which made kidnapping a federal crime, Director J. Edgar Hoover’s men tracked the case relentlessly. Arrests of Kathryn Kelly’s relatives broke open the conspiracy, leaving George cornered and desperate.

For a figure who had carefully burnished the “Machine Gun” image—mugging for photographers with his Thompson submachine gun, boasting of his toughness—the surrender was a humiliation. Witnesses said he begged for his life, his famous words more plea than bravado. Yet in that moment of weakness, he inadvertently gave Hoover the branding victory he craved.

The FBI, still a young agency, seized on the episode. Hoover had long sought to recast his agents as disciplined, scientific, incorruptible—the opposite of the chaotic, romanticized criminals glamorized in tabloids. Kelly’s downfall fit the narrative perfectly: the G-Men had prevailed where local police could not. Hollywood soon joined in, turning “G-Man” into a cultural symbol of order and justice.

Kelly and his wife were swiftly convicted and sentenced to life in prison. He would spend the next two decades behind bars, dying in Leavenworth in 1954. Kathryn, thought by many to be the more calculating partner, also served decades before her eventual release. Their fall was a signal moment in the federal war on crime—a turning of the tide from the gangster era to the age of Hoover’s Bureau.

The 1930s would still bring John Dillinger, Bonnie and Clyde, and “Pretty Boy” Floyd, but the balance had shifted. The men with badges, now known to all as G-Men, had claimed the upper hand. And it was a frightened gangster, surrendering on September 26, 1933, who gave them their name.