When Isabella Mary Beeton’s Book of Household Management appeared on October 1, 1861, few could have anticipated the reach and endurance of what became the most famous domestic manual of the Victorian age. Selling some 60,000 copies in its first year alone, the work instantly established itself as a fixture in middle-class homes and has remained in print continuously to the present day—a testament to its blend of practical instruction and cultural resonance.

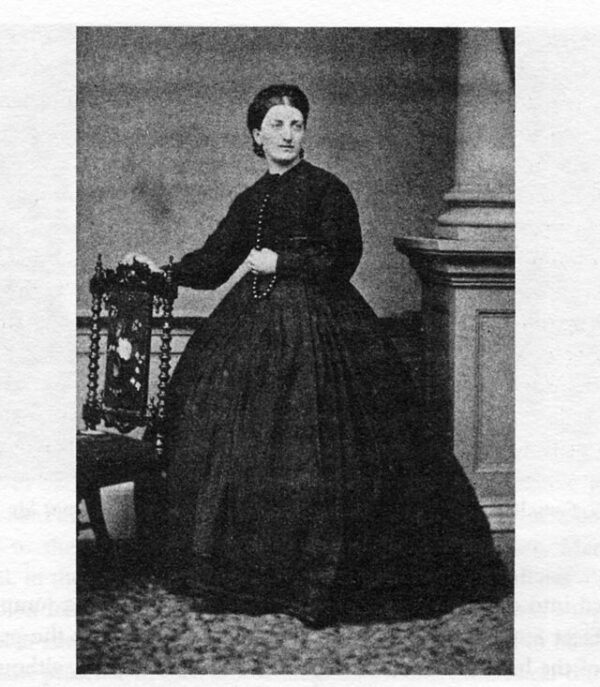

The author herself was not the matronly grande dame that later legend imagined, but rather a young woman in her mid-twenties, married to publisher Samuel Beeton. Their enterprise drew upon an emerging market: a growing literate middle class of women tasked with running households that had grown more complex in scale and expectation. England in the 1860s was a nation of aspiring respectability, where the ordering of the home reflected not only personal virtue but also social status. To that audience, Mrs. Beeton offered clarity, authority, and system.

The Book of Household Management was nothing less than encyclopedic in scope. It contained recipes—over 900 of them—but it was also a guide to staff management, child-rearing, medical care, and the budgeting of a Victorian household. It treated the home as a kind of miniature kingdom, requiring not only affection and instinct but also the discipline and organization associated with the public sphere. By giving housewifery the dignity of a profession, Mrs. Beeton elevated domestic labor in a way that resonated with her contemporaries.

Part of the volume’s appeal lay in its tone: brisk, confident, and reassuring. “As with the commander of an army,” Mrs. Beeton wrote, “so it is with the mistress of a house.” The analogy underscored both the responsibilities and the anxieties of her readers. Here was not merely a recipe book but a manual of command. By drawing upon the language of order, regimentation, and moral duty, Beeton reassured women that their private sphere was no less vital than the public arenas from which they were largely excluded.

The book’s success was amplified by the entrepreneurial acumen of Samuel Beeton, who serialized his wife’s work in The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine before compiling it into the single, massive volume that appeared in 1861. The result was an immediate sensation. Its sales figures rivaled those of Dickens and Thackeray, and unlike many works of fiction, it remained a perennial purchase by successive generations setting up new households. Each copy represented not merely a literary sale but an initiation into a shared cultural code of domesticity.

Yet Mrs. Beeton’s own life was brief and shadowed. She died in 1865 at the age of 28, after complications in childbirth, leaving behind her famous book as her enduring monument. That early death allowed the myth to grow: “Mrs. Beeton” became less a living author than a brand, a household name detached from biography, synonymous with the domestic arts. Later editions, often heavily revised by others, continued to appear under her name, creating the impression of an ageless oracle of Victorian household wisdom.

The endurance of the Book of Household Management owes much to its adaptability. Successive editors updated recipes, adjusted instructions, and modernized details, but the core spirit—the idea that the home required method and intelligence—remained intact. In this sense, Mrs. Beeton’s book was not simply a mirror of Victorian domestic life but a shaper of it, codifying ideals of order, respectability, and female authority within the household.

More than 160 years after its debut, the work is still in print, an artifact of a vanished age but also a reminder of how knowledge, once codified, can outlive its context. On October 1, 1861, Isabella Beeton gave the world a book that would shape the daily rituals of countless households. Its sales proved its popularity; its survival proves its significance.