In the predawn hours of October 2, 1835, a column of Mexican dragoons rode toward the small frontier settlement of Gonzales. Their mission, routine in the eyes of Mexican authorities, would prove incendiary: they had come to reclaim a small cannon loaned to the town four years earlier as a defense against Comanche raids. Yet in the charged atmosphere of Texas—where Anglo-American settlers and the centralizing government of President Antonio López de Santa Anna were already on a collision course—this seemingly minor act became the spark of open rebellion.

The cannon, little more than a six-pounder mounted on rough wheels, had acquired symbolic weight far beyond its military utility. To the settlers, many of them recent immigrants from the United States, surrendering the piece would be tantamount to admitting their subordination. It was not simply a weapon; it was a marker of autonomy and communal resolve. Thus, when word reached Gonzales that Mexican officers demanded its return, the townspeople delayed, stalled, and finally refused.

Captain Francisco de Castañeda was dispatched with some 100 dragoons to enforce compliance. When he reached the Guadalupe River opposite Gonzales on September 29, he found the ferry dismantled and local militia gathering on the far bank. Messages passed back and forth, but the Texans—though disorganized—were united in defiance. They needed time, and they bought it cleverly. Women ferried the militia’s calls for aid to surrounding settlements, while younger men harassed the soldiers from across the river. In the days that followed, volunteers poured in until nearly 150 Texians were mustered.

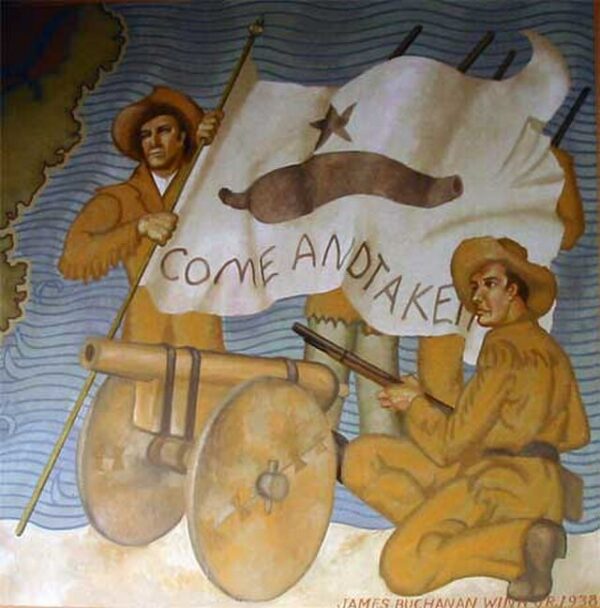

On the night of October 1, they resolved to act. Concealing the contested cannon under a white flag daubed with a black star and the words “Come and Take It,” the insurgents prepared to cross the river at dawn.

The clash that followed on the morning of October 2 was small in scale—more skirmish than battle—but vast in consequence. The Texians, commanded by John H. Moore, advanced toward Castañeda’s encampment in the mist. Shots rang out, though casualties were few. The Texans discharged their treasured cannon, scattering the cavalry and marking the first artillery fire of what would soon become the Texas Revolution.

Castañeda, outnumbered and lacking orders to escalate, prudently withdrew. He reported afterward that he had no desire to begin a war, and his men retreated toward San Antonio. But the Texians seized upon the event as a triumph. Though only a handful of men had fallen, the skirmish carried the psychological weight of Lexington and Concord half a century earlier. A people had chosen resistance over submission.

The Gonzales affair reverberated quickly across the province. Settlers who had wavered now rallied to the cause. Newspapers in the United States seized upon the story, likening the “Come and Take It” flag to the banners of American independence. For Santa Anna’s regime, the confrontation marked the breakdown of compromise; the colonists had fired upon Mexican troops, and rebellion could no longer be treated as mere grumbling.

Within weeks, Texian forces marched on Béxar, laying siege to Mexican troops under General Martín Perfecto de Cos. What began as a dispute over a small cannon hardened into a war for sovereignty.

In retrospect, the fight at Gonzales revealed the combustible mixture of local grievance and ideological conviction. The settlers were motivated by immediate fears—loss of arms, loss of self-defense—but also by a broader vision of rights and liberties rooted in their Anglo-American political culture. To Mexican officials, the refusal was a challenge to national authority; to the Texians, it was an assertion that they would govern themselves.

Thus, the morning of October 2, 1835, stands not merely as a frontier skirmish but as a declaration. A town of fewer than 200 residents confronted imperial power and set in motion a revolution. The “Lexington of Texas” had been fought, and the course toward independence was fixed.