On October 4, 1535, a landmark in the history of faith, politics, and language took place: the first complete Bible printed in English, known ever after as the Coverdale Bible. Though it bore the name of Myles Coverdale, an Augustinian friar turned reformer, the translation was in large part the work of William Tyndale—the fiery and brilliant linguist whose defiance of both Rome and crown led to his imprisonment and execution. If Tyndale was the architect, Coverdale was the builder who brought the project to completion, giving England a printed Scripture at a moment when such a feat was both dangerous and revolutionary.

The background is crucial. For centuries, the Catholic Church had resisted vernacular translations, arguing that Scripture should remain in Latin, the preserve of trained clergy. The memory of John Wycliffe’s hand-copied English Bible in the 14th century still lingered, associated with heresy and rebellion. Yet the Reformation, beginning with Martin Luther’s German Bible, unleashed a wave of vernacular translations across Europe. England, however, was perilous ground. Henry VIII had broken with Rome, yes, but he was hardly ready to allow uncontrolled access to Scripture. Tyndale himself had fled England, living in exile on the Continent, smuggling portions of his English New Testament back into his homeland hidden in bales of cloth.

Tyndale’s pen was fearless. His crisp, muscular English—phrases like “let there be light” and “the powers that be”—would shape the very rhythms of English prose and later echo in the King James Bible. But his career ended in betrayal: arrested in Antwerp in 1535, he was strangled and burned at the stake the following year. His dying prayer—“Lord, open the King of England’s eyes”—would prove prophetic.

Enter Myles Coverdale. Less a fiery polemicist than Tyndale, Coverdale was a careful compiler. Drawing heavily from Tyndale’s published New Testament and portions of the Old, Coverdale filled in the gaps using Luther’s German Bible and the Latin Vulgate. His genius was not in original translation so much as in completion. Working abroad, possibly in Zurich or Antwerp, he oversaw the printing of a complete English Bible in folio. It bore a dedication to Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn—an act of political calculation, hoping to win protection for a book that in other times might have cost him his life.

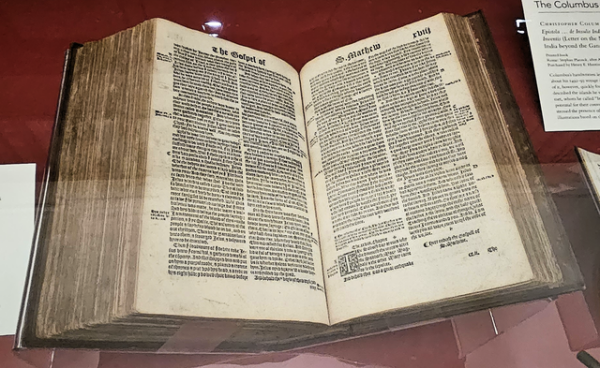

The result was extraordinary. Bound volumes containing both Old and New Testaments in English rolled off the presses, shipped into England under discreet cover. The title page proclaimed it was “faithfully and truly translated out of Douche [German] and Latyn into Englishe,” avoiding direct mention of Tyndale, who was officially condemned. Yet anyone familiar with the prose could recognize Tyndale’s fire in its pages.

Reception was mixed. Reformers rejoiced: at last, ordinary men and women could hear the whole counsel of God in their own tongue. Passages that once echoed only in Latin liturgy now spoke in the familiar cadences of English. But bishops and conservatives bristled, wary of laypeople interpreting Scripture without clerical guidance. The king himself vacillated, alternately tolerating and restricting distribution. Still, the tide was turning. Within a few years, other versions—the Matthew Bible, the Great Bible—would appear, drawing on the foundations laid by Tyndale and Coverdale.

The Coverdale Bible thus marks a hinge in English religious and literary history. It was not perfect—Coverdale himself admitted his dependence on secondary sources, and later translations surpassed it in accuracy—but it was the first. And being the first, it carried immense symbolic weight. To hold an English Bible in one’s hands in 1535 was to feel the promise of the Reformation itself: that God’s word was not the monopoly of priests or princes, but a voice that could speak directly to shepherds, merchants, and kings alike.

October 4, then, deserves remembrance not merely as a date in publishing history but as a milestone in liberty. For the English Bible was more than a book—it was a declaration of intellectual and spiritual independence. The Coverdale Bible lit the path that would lead, through blood and struggle, to the majestic King James Version of 1611 and to the enduring place of biblical English at the heart of Western culture.