On the evening of October 8, 1969, Chicago’s Grant Park became the staging ground for one of the most explosive and controversial protests of the Vietnam era—the opening rally of the “Days of Rage.” Organized by the Weather Underground, a radical splinter faction of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the rally marked the group’s public debut as a militant revolutionary force determined to bring the Vietnam War home. What began as a call to “bring the war to the streets” would spiral into chaos, leaving downtown Chicago scarred and the American left fractured.

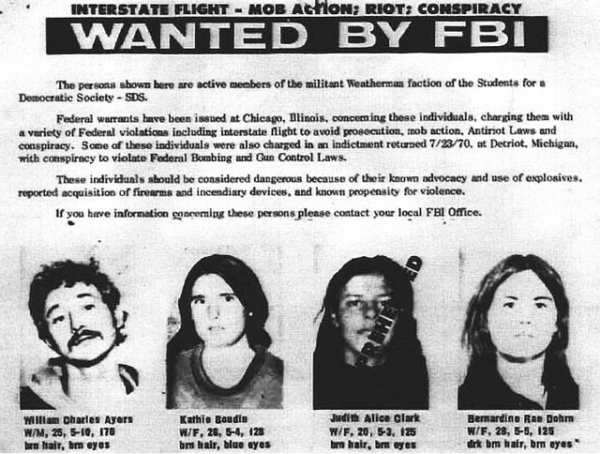

The Weather Underground—its name derived from a Bob Dylan lyric, “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows”—emerged from the ruins of a disintegrating SDS, whose leadership had grown increasingly divided over questions of violence and ideology. Convinced that America’s political system was irredeemably corrupt, and that peaceful protest had failed to halt the carnage in Vietnam or the oppression of Black Americans at home, the group’s founders—including Bill Ayers, Bernardine Dohrn, Mark Rudd, and Jeff Jones—embraced confrontation as a moral imperative. Their goal was nothing less than revolution.

The “Days of Rage” were announced as a four-day campaign of “direct action” to “disrupt the empire” and demonstrate solidarity with the Viet Cong and Black liberation movements. Posters plastered across college campuses urged participants to “Bring the War Home.” Organizers promised thousands of radicals would descend upon Chicago to avenge the deaths of Che Guevara and Black Panther leader Fred Hampton and to challenge the Democratic establishment symbolized by Mayor Richard J. Daley’s police force.

But when the moment came, the turnout was pitiful—perhaps 300 protesters against an army of 2,000 helmeted police. Undeterred, the Weather Underground’s leaders sought to make a spectacle of defiance. “We’re against everything that’s good and decent in honky America,” declared Dohrn from the rally’s podium. “We will burn and loot and destroy. We are the incubation of your mother’s nightmare.” Her words electrified the small but fervent crowd, who soon surged toward the affluent Gold Coast neighborhood, smashing car windows and hurling rocks at police lines.

What followed was a running street battle more evocative of guerrilla warfare than political demonstration. Protesters—some wearing helmets, others brandishing clubs—charged through downtown Chicago, overturning cars and breaking storefront glass. Police countered with tear gas, clubs, and mass arrests. By the end of the first night, dozens were injured, and nearly 100 had been arrested. The clashes continued sporadically over the next several days, as the group attempted to regroup and launch further assaults on symbolic targets, including a draft board and a police station.

The violence shocked much of the antiwar movement, alienating even those sympathetic to its goals. Many veterans of peaceful protest condemned the Weather Underground as self-destructive and delusional. Yet for its members, the Days of Rage were not a failure but a baptism—a test of will that proved their commitment to revolution. As Bill Ayers would later recall, “We saw ourselves as a small part of the world revolution, and the Days of Rage were our declaration of war.”

In the months that followed, the group went underground, adopting clandestine tactics modeled on Latin American insurgencies. Bombings of government buildings, police stations, and corporations followed throughout the early 1970s, justified as acts of “armed propaganda.” But the bloody rhetoric of 1969 never produced the mass uprising the Weathermen envisioned. Instead, it left behind a legacy of broken lives, shattered ideals, and an enduring debate over the limits of dissent in a democracy.