On October 17, 1907, the world awoke to a quieter revolution—one not of engines or empires, but of invisible waves crossing the Atlantic. That day, Guglielmo Marconi’s transatlantic wireless telegraph service officially began operations, linking Clifden, Ireland, with Glace Bay, Nova Scotia. For the first time in history, nations could communicate across oceans not through ships and cables but through the air itself. What began as a spark in Marconi’s imagination had become a technological reality: the first commercial wireless communication between Europe and North America.

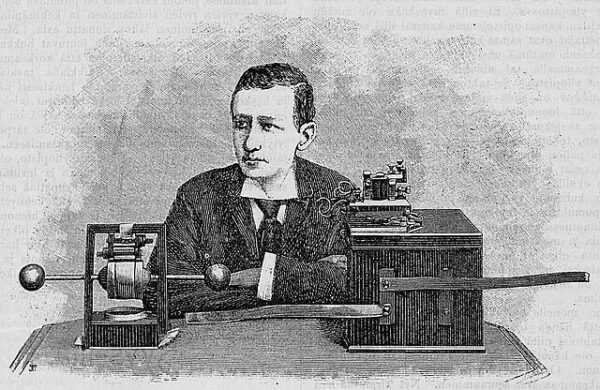

Marconi, the Italian-born engineer often called the father of radio, had spent more than a decade perfecting his vision. As early as 1895, he had demonstrated that electromagnetic waves could carry signals over long distances without wires. By 1901, he had stunned the scientific community by sending the letter “S” in Morse code from Cornwall, England, to St. John’s, Newfoundland—proof that radio waves could leap the curvature of the Earth. But that early triumph was fragile and inconsistent. Static, atmospheric interference, and erratic transmissions plagued the system. The 1907 service represented a far greater achievement: working commercial network, robust enough for governments, businesses, and newspapers to rely upon daily.

The route itself symbolized both technological ambition and imperial geography. Clifden, a remote coastal outpost in western Ireland, was chosen for its clear signal path and isolation from electrical interference. Glace Bay, perched on the eastern edge of Canada, mirrored it across the Atlantic. Between them stretched nearly 2,100 miles of water—a vast space that had previously demanded undersea telegraph cables, costly to lay and prone to damage. Marconi’s wireless stations stood as twin monuments to the age of electromagnetic communication, each with towering masts over 200 feet high and massive spark transmitters capable of generating signals at tens of kilowatts.

Messages transmitted between the two sites were initially confined to Morse code telegrams, sent at a cost of sixpence per word—cheaper than some cable routes, but still a luxury. The early customers were shipping firms, government offices, and news agencies eager for faster transatlantic correspondence. The implications were profound. In an instant, the tyranny of distance that had defined centuries of global communication began to erode. Maritime safety improved as ships could report their positions and emergencies from far out at sea. Political leaders could coordinate across continents with unprecedented speed. The world was becoming smaller, more synchronized, more modern.

Marconi’s success was not without rivalry. Cable companies, alarmed by the new wireless threat to their monopoly, dismissed his claims and questioned his reliability. Even some physicists doubted that long-range transmission was possible without the help of ionospheric reflection—a phenomenon not yet understood at the time. But the proof was in the results: messages reliably crossed the Atlantic day after day. The British Admiralty soon adopted wireless communication, and by 1912—spurred by the Titanic disaster—the international maritime community made radio a standard requirement for all major vessels.

Marconi’s system, initially cumbersome and sparking with electrical violence, soon evolved into a cleaner, more efficient technology. Continuous-wave transmitters replaced the old spark gaps, allowing clearer signals and even the transmission of sound. Within a generation, the wireless telegraph had become the wireless telephone—and then, simply, “radio.” The very idea of instantaneous communication across oceans laid the groundwork for the global information networks of the twentieth century, from shortwave broadcasting to satellite relays and the internet itself.

The Clifden and Glace Bay stations operated until 1917, when wartime security concerns led to their closure. Yet their legacy endured. They marked the point at which human communication ceased to be bound by geography. On that October day in 1907, when the first commercial signal leapt across the Atlantic, it carried more than dots and dashes—it carried a new definition of connection.