On October 26, 1892, Ida B. Wells—teacher, journalist, and civil rights crusader—published Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, one of the most searing indictments of racial terror ever printed in the United States. In just thirty pages, Wells exposed the grotesque machinery of mob violence that defined the post-Reconstruction South, transforming what many white Americans called “frontier justice” into what she identified plainly as a system of racial control and political suppression.

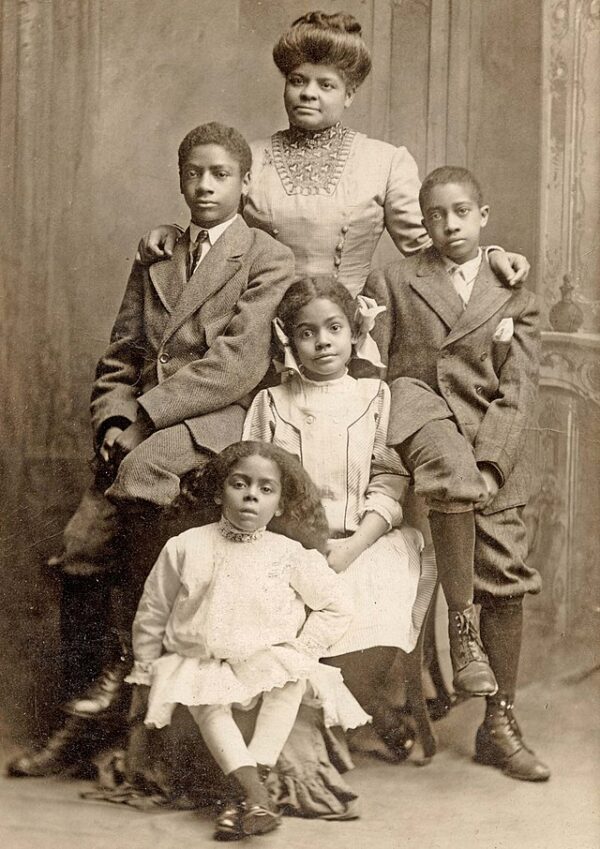

Born enslaved in 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi, Wells had come of age in the shadow of emancipation and the false dawn of Reconstruction. By her early thirties, she was already co-owner and editor of the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight, where she began investigating lynchings that followed the collapse of Reconstruction governments. The catalyst for Southern Horrors came in 1892, when three of her friends—Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart—were lynched in Memphis after defending their grocery store against a white rival. Wells’s editorials condemning the murders enraged local whites; a mob destroyed her newspaper office and threatened her life, forcing her to flee to Chicago. Exile, however, did not silence her—it radicalized her.

In Southern Horrors, published later that year, Wells combined eyewitness reporting, legal analysis, and moral indictment. She challenged the dominant myth that lynching was a response to Black men raping white women. “Nobody in this section of the country believes the old threadbare lie,” she wrote, documenting how most lynchings followed economic competition, political assertion, or mere rumor. Through meticulous citation of newspaper accounts, she revealed that “the men who were killed were not always accused of crime at all.” Her report was both statistical and prophetic, naming cases, counties, and victims to demonstrate that lynching was not spontaneous but systemic—an extrajudicial enforcement of white supremacy.

The pamphlet’s three main sections—“The Offense,” “The Black and White of It,” and “The Remedy”—progressed from exposure to confrontation. Wells detailed the hypocrisy of white southern society, which condoned sexual exploitation of Black women while crying outrage over supposed assaults on white womanhood. She argued that lynching served not to protect virtue but to suppress Black progress and self-defense. In her concluding section, she called for boycotts, migration, and armed self-protection: “A Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every Black home.” Her words shattered the politics of respectability that dominated even many northern reform circles, forcing readers to confront the brutal realities of race and power.

The immediate reaction was explosive. Southern newspapers branded her “a slanderous and black-hearted creature.” Yet northern audiences, particularly among African Americans and women’s suffrage groups, rallied behind her. The pamphlet circulated widely through Black churches, labor halls, and civic organizations, becoming a foundational text of the nascent anti-lynching movement. Wells embarked on speaking tours across Britain in 1893 and 1894, exposing international audiences to America’s racial hypocrisy. British activists, shocked by her documentation, pressured U.S. officials and church groups to denounce lynching publicly.

Southern Horrors was followed in 1895 by The Red Record, an even more comprehensive statistical chronicle of lynching, which listed over two hundred cases from 1892 alone. Together, these works forged a new template for investigative journalism and moral protest. Wells’s fusion of data and indignation anticipated later muckraking traditions and established her as one of the first major figures in American investigative reporting.

Beyond its journalism, Southern Horrors redefined the moral vocabulary of American democracy. Wells insisted that truth-telling was itself an act of resistance. At a time when the federal government refused to intervene against mob violence, her pamphlet stood as both evidence and indictment—proof that democracy had failed its most vulnerable citizens. Her courage inspired later generations of activists, from the NAACP founders (she was one of them) to the civil rights leaders of the 1950s and 1960s who carried her legacy of fearless exposure.

By the time of her death in 1931, Wells had spent nearly four decades battling indifference, distortion, and danger. But the words she first published on October 26, 1892, still echo with defiance: that justice cannot coexist with lies, and that a nation’s conscience begins where its silence ends.