In the autumn of 1888, beneath the vast African sky of Matabeleland, a seemingly routine agreement was inked between British traders and a local monarch. Yet the document—later known as the Rudd Concession—would alter the map of southern Africa and inaugurate a new stage of imperial ambition. On October 30, King Lobengula, ruler of the Ndebele (Matabele) kingdom, affixed his mark to a contract granting mineral rights across his realm to agents of Cecil Rhodes. It was, in effect, the first legal step toward the creation of Rhodesia and the consolidation of British power north of the Limpopo.

The concession’s architects were three representatives of Rhodes’s mining and political interests: Charles Rudd, James Rochfort Maguire, and Francis Thompson. Their mission was clear—to secure exclusive rights to the vast mineral resources rumored to lie beneath Matabeleland’s soil, particularly gold. In return, Lobengula was promised £100 per month, 1,000 rifles, 100,000 rounds of ammunition, and a steam-powered riverboat. To the king, whose people had already encountered white traders and fortune-seekers, these inducements seemed tangible and immediate. The document, however, was couched in legal English that obscured its true breadth: it effectively transferred all mineral rights in his dominions to Rhodes and his backers in perpetuity.

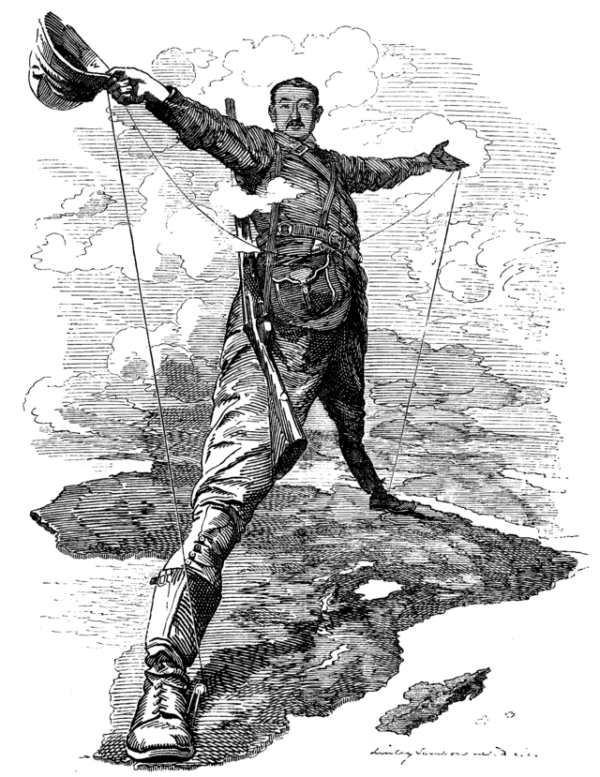

Cecil Rhodes, then expanding his British South Africa Company with the dream of building a continuous British dominion from the Cape to Cairo, hailed the concession as a triumph. The chartered company he established soon afterward would claim Matabeleland and Mashonaland as part of its sphere of influence, receiving a royal charter from Queen Victoria in 1889. For Britain, the Rudd Concession was the keystone of its imperial advance into central Africa—a paper claim that quickly became political reality through military and administrative force.

For Lobengula, the outcome was disastrous. He soon realized that he had been deceived into signing away far more than he intended. Missionaries and independent traders who knew the king warned him of Rhodes’s duplicity, prompting Lobengula to send envoys to Queen Victoria in 1889 to protest that he had been tricked. But by the time his appeal reached London, the machinery of empire was already in motion. The British South Africa Company’s charter had been approved, and Rhodes’s private empire—sanctioned by royal authority—was on its way to transforming southern Africa.

The concession’s legacy extended far beyond the immediate dispute over its legality. It epitomized the pattern of European imperial expansion through private enterprise, backed by official endorsement. Like the treaties of the East India Company two centuries earlier, the Rudd Concession blurred the line between commercial contract and colonial annexation. Rhodes’s company would later use it as justification for military campaigns against both the Ndebele and the Shona, culminating in the establishment of Southern and Northern Rhodesia—modern Zimbabwe and Zambia.

Historians have long debated whether Lobengula truly understood what he had signed. Some argue that the king, aware of the growing European presence, sought to balance competing powers and gain weapons to defend his people. Others see the concession as a masterpiece of imperial deceit, a symbol of how European ambition exploited African trust and linguistic confusion. In either view, the agreement stands as a cautionary moment: an instance when a single signature, extracted under ambiguous circumstances, allowed a continent’s fate to be rewritten in favor of empire.

The Rudd Concession’s importance lies not only in its immediate consequences but in what it represented—the fusion of commerce, diplomacy, and conquest in the high age of imperialism. It demonstrated how a mining syndicate could become a colonial state and how a frontier king could be undone by the abstractions of international law. On October 30, 1888, Lobengula’s ink and Rhodes’s ambition merged on a single sheet of paper, and from that act emerged the geopolitical foundations of modern southern Africa.