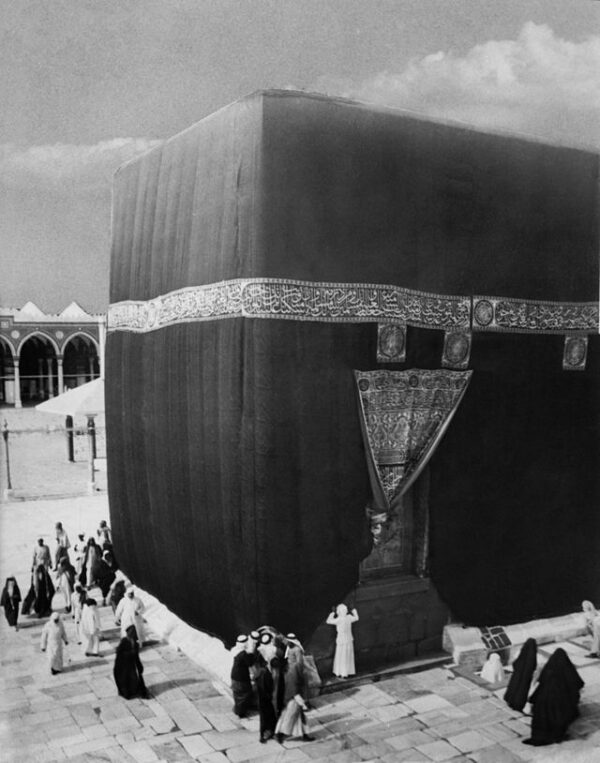

On October 31, 683 A.D., fire consumed the holiest sanctuary in Islam. During the bloody Siege of Mecca—the climax of the Second Fitna, or second great Muslim civil war—the Kaaba itself was set ablaze amid fierce fighting between the Umayyad Caliphate and the rebel forces of ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr. What began as a political struggle for legitimacy ended that day in an act of devastation that shocked the Muslim world: the burning of the House of God.

The turmoil had begun months earlier, after the death of Caliph Muʿāwiyah I, founder of the Umayyad dynasty. His son Yazid I succeeded him in 680, igniting opposition across the Islamic empire. To many Muslims, Yazid’s rule marked the corruption of the caliphate into a hereditary monarchy. In Mecca, Ibn al-Zubayr—grandson of Abu Bakr, the first caliph after Muhammad—refused to pledge allegiance. His defiance made the city a symbol of resistance and a target for Damascus.

In September 683, Yazid dispatched a large force under the command of Husayn ibn Numayr to crush the rebellion. Mecca was fortified, but the siege soon tightened, cutting off water and provisions. The Umayyads deployed catapults from the surrounding hills, hurling stones and flaming projectiles toward the city’s defenders. The sanctity of Mecca, long held inviolable even in times of war, was broken. The thud of siege engines replaced the chants of pilgrims.

Then came the calamity. On or about October 31, one of the fire-laden projectiles overshot its mark and landed inside the precincts of the Masjid al-Haram. Within moments, the Kaaba—the cube-shaped shrine at the center of Islam’s holiest mosque—was ablaze. The curtains that draped its walls caught fire first, followed by the wooden beams and lead roof. The conflagration burned through the night as defenders and besiegers alike watched in horror. When the flames finally subsided, the building was a ruin: its walls cracked, its roof collapsed, and the Black Stone—venerated as a relic from heaven—shattered into fragments.

The moral shock reverberated far beyond Arabia. To pious Muslims, the destruction of the Kaaba symbolized a world unmoored—a divine rebuke to rulers who had violated the sacred. Even some within the Umayyad ranks were horrified that catapults had been turned upon the sanctuary established by Abraham and purified by Muhammad. Yet the siege dragged on until news arrived that Yazid I had died unexpectedly in Damascus. His army withdrew, and Ibn al-Zubayr emerged not only as the master of Mecca but as the spiritual heir of resistance to tyranny.

In the months that followed, Ibn al-Zubayr ordered the Kaaba rebuilt. He replaced its burned timbers with solid stone, expanded the structure to include the semi-circular ḥatim—believed to mark the foundation of Abraham’s original design—and restored the Black Stone, now bound in silver. The reconstruction became both an act of faith and a declaration of independence. Mecca, once again, was the center of a rival caliphate.

But history soon turned. In 692, the Umayyads retook the city under Caliph ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān. Ibn al-Zubayr was killed, and the Kaaba was rebuilt yet again—this time returned to the dimensions remembered from the Prophet’s time. The empire reclaimed its holy center, but not its moral innocence.

The burning of the Kaaba on October 31, 683, remains one of the darkest episodes in Islamic history. It was more than the destruction of a building; it was a wound to the unity of the Muslim world, a moment when faith and politics collided in fire. Out of that blaze, Mecca would rise again, but the memory endured—a warning written in smoke across the holiest sky.