As cold winds swept across New England, the uneasy peace between the English colonists and the region’s Native nations finally broke apart. On this day, Plymouth Colony governor Josiah Winslow led a combined colonial militia into the field against the Narragansett, marking a critical escalation in what would become one of the bloodiest conflicts in early American history: King Philip’s War.

The war had erupted months earlier when Metacom—called King Philip by the English and son of the Wampanoag leader Massasoit—rallied neighboring tribes to resist the colonists’ relentless expansion. His grievances ran deep: the steady seizure of Native lands, the undermining of tribal sovereignty, and the execution of Wampanoag men under colonial law. When his followers attacked the frontier town of Swansea in June 1675, New England’s fragile balance collapsed. Settlements burned from Rhode Island to Maine. The English colonies, divided by jurisdiction and rivalry, hastily united in common cause. At the head of the confederated forces stood Josiah Winslow, the stern and pious governor of Plymouth, whose leadership would soon be tested in fire and frost.

By autumn, colonial suspicion turned toward the Narragansett. Although they had not openly joined Philip’s uprising, English reports claimed that the tribe was harboring Wampanoag refugees and stockpiling arms. Winslow and his allies in Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut decided to strike preemptively. On November 2, 1675, Winslow mustered nearly a thousand soldiers—English militiamen joined by Pequot and Mohegan scouts—and marched into the wilderness of southern Rhode Island. The campaign’s goal was to force the Narragansett to surrender their Wampanoag guests and pledge neutrality. It quickly became something far harsher: a punitive expedition that would culminate, weeks later, in the infamous Great Swamp Fight.

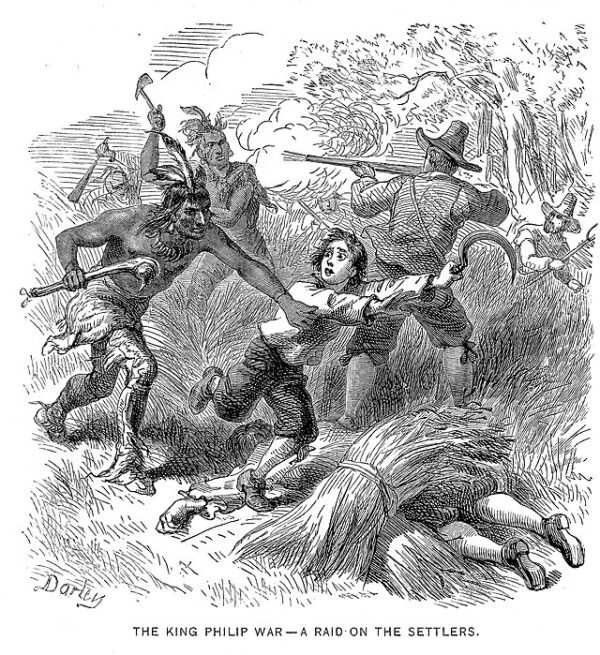

The men slogged through swamps and thickets as winter deepened, cutting supply trails through frozen bogs. Skirmishes flared when colonial scouts clashed with Narragansett sentinels, and both sides suffered early losses. Winslow’s forces destroyed food stores, burned wigwams, and took captives—actions meant to cripple any potential alliance between Philip and the Narragansett sachem Canonchet. But these assaults only convinced the Narragansett that neutrality was impossible. They began fortifying a stronghold deep in the Great Swamp, preparing for the inevitable siege.

When Winslow and his troops finally reached that palisaded village in December, the confrontation erupted into the Great Swamp Fight—a brutal battle fought amid ice and fire. Colonial soldiers stormed the walls and set the settlement ablaze. Hundreds of Narragansetts, including women and children, were killed or burned alive; many others perished from exposure after fleeing into the frozen wilderness. Winslow’s men claimed victory but paid dearly in frostbite, wounds, and death.

Contemporary chroniclers portrayed Winslow as a deliverer of New England from “heathen fury,” yet history remembers the assault as a massacre. The Narragansett nation—once the region’s most powerful—was shattered. Survivors joined Philip’s dwindling coalition in a last, desperate attempt to drive out the English. But the tide of the war had turned. The colonies, devastated yet unified by shared suffering, pressed on through 1676 until Philip was hunted down and killed that August, his head displayed in Plymouth as a grim trophy.