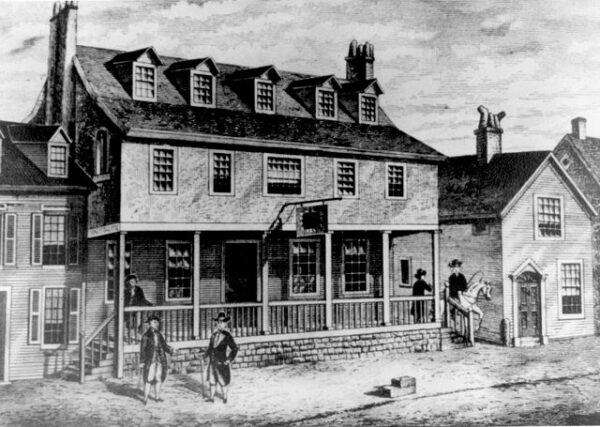

The creation of the United States Marine Corps on November 10, 1775, at Philadelphia’s Tun Tavern stands as one of the most durable institutional legacies of the American Revolution. Conceived in the early weeks of the war—when the Continental Congress urgently sought to build a naval force capable of challenging British command of the seas—the Marine Corps emerged as an elite amphibious arm designed to operate in the narrow space between soldiers and sailors. The man appointed to shape this new force, Samuel Nicholas, was a Philadelphia merchant and prominent member of local militia circles. Though his formal commission identified him simply as a captain, tradition and subsequent recognition place him as the first Commandant of the Marine Corps.

The decision to raise Marines reflected the strategic anxieties of 1775. Britain’s fleet was the most formidable in the world, and any American effort to contest imperial authority along the coast required a naval component. But warships alone were insufficient. Congress needed troops who could fight aboard vessels, execute boarding actions, serve as sharpshooters high in the rigging, enforce shipboard discipline, and land quickly in contested harbors. Drawing on British precedent—the Royal Marines had existed since the 1660s—the Marine Committee authorized two battalions of Continental Marines. Their instructions were deliberately broad: join the new Continental Navy, perform sea-based combat duties, and undertake amphibious strikes when necessary.

Tun Tavern provided a natural recruitment point. Located near the Philadelphia waterfront, it was a well-known gathering place for sailors, merchants, and militiamen. Nicholas, relying on his family’s connections, used the tavern as both an organizational hub and a site for attracting adventurous recruits. The early Marines were expected to be men capable of enduring the harsh conditions of naval warfare: cramped quarters, violent shipboard engagements, and sudden deployment ashore. They also had to possess enough discipline to operate within the strict hierarchy of a warship—a contrast to the more relaxed, often politically fractious environment of the Continental Army.

The Marines saw action almost immediately. Nicholas and a detachment of his newly raised force embarked with Commodore Esek Hopkins’s squadron on its 1776 Caribbean expedition. The most notable engagement occurred at New Providence in the Bahamas, where Marines conducted one of the first amphibious assaults in American history. Landing under fire, they seized British stores of gunpowder and munitions—supplies desperately needed by Washington’s army. Though strategically modest, the operation showcased the fast-strike capabilities that would define Marine identity for generations.

Throughout the Revolution, Continental Marines served aboard various naval vessels, participating in engagements against British ships, protecting officers, and maintaining order among often unruly seamen. Their role as marksmen proved especially valuable. In the age of sail, musket fire from the fighting tops could determine the outcome of close-quarters naval combat. Marines were expected to remain steady even as ships pitched violently beneath them or splintered under cannon fire.

Meanwhile, on land, Nicholas worked to keep the Corps intact despite chronic shortages of money, equipment, and recruits. The Marines never reached the full size envisioned by Congress, but their performance won respect among naval commanders. When Philadelphia fell to the British in 1777, Nicholas oversaw the orderly withdrawal of Marine forces, continuing operations from new bases as the war shifted south and eventually back toward the Atlantic seaboard.

The formal disbandment of the Continental Navy after the war led to the temporary dissolution of the Marine Corps. Yet the institution’s reputation endured, and when the United States reestablished a naval force in the 1790s to confront French privateers, Congress simultaneously reconstituted the Marines. The lineage of today’s Corps thus flows directly from the small, improvised force Nicholas organized at Tun Tavern during the Revolution’s uncertain early months.

The Corps blended naval functionality with infantry rigor, forging an identity built on adaptability, discipline, and aggressive action. The amphibious ethos established under Nicholas—rooted in the needs of a fledgling nation fighting for survival—became a permanent feature of U.S. military doctrine. The men who gathered in that Philadelphia tavern laid the foundation for a force that would, over centuries, become synonymous with expeditionary readiness and the nation’s projection of power abroad.