On a damp, gray Tuesday evening that did little to distinguish itself from any other in the British capital, a quiet technological revolution began. At precisely 6:00 p.m., the British Broadcasting Company — a consortium of leading wireless manufacturers — officially launched its first daily radio service, inaugurating what would become one of the most influential institutions in modern public life. Few in Britain fully grasped the significance of the moment. Fewer still imagined that the tentative crackle of that inaugural broadcast would evolve into a national voice, shaping culture, politics, and civic identity for generations.

The debut program originated from a modest studio in Marconi House on the Strand, where a small staff of engineers and announcers worked with equipment that, by later standards, was painfully primitive. The first voice to greet listeners belonged to Arthur Burrows, serving as the fledgling company’s Director of Programmes. His greeting was simple and direct, a reflection of the medium’s novelty: “This is 2LO calling.” With that understated phrase, Britain entered the broadcasting age.

At its founding, the British Broadcasting Company was not a government body but a private joint venture formed by firms eager to sell radio sets. The government, wary of unregulated transmissions and mindful of the chaos unfolding on the American airwaves, had opted for a tightly controlled alternative. Manufacturers could operate the service collectively, but the Post Office would retain authority over licensing and technical standards. This unusual public-private arrangement meant that radio in Britain would grow under a more centralized and disciplined structure than elsewhere — a feature that would come to define the character and credibility of British broadcasting.

The early programming schedule was modest: news bulletins, musical performances, weather reports, and short talks on practical subjects. Yet even these simple offerings carried an unmistakable sense of national cohesion. In the years immediately following the First World War — a period marked by economic strain, political unrest, and social uncertainty — the prospect of a shared auditory experience offered something close to civic reassurance. The newspapers, recognizing both the power and the threat of the new medium, lobbied fiercely to restrict radio news, and for a time succeeded in forcing the BBC (as it soon became known) to read only bulletins supplied by the press. Even so, the public appetite for this new form of mass communication grew rapidly.

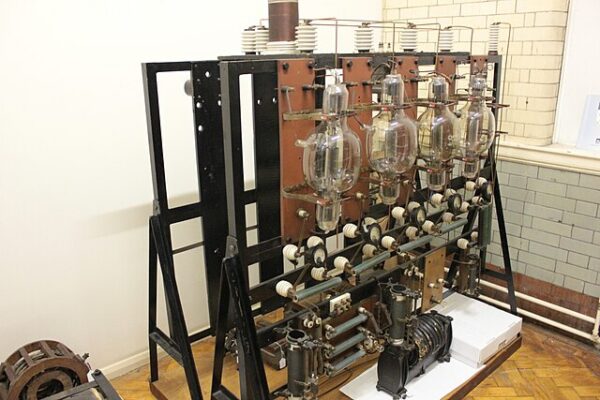

Technologically, the challenges were immense. Broadcasting required not only transmission towers and reliable receivers but also rigorously trained operators who understood the quirks of early vacuum-tube equipment. The British Broadcasting Company’s engineers often worked long into the night to improve clarity, reduce interference, and expand coverage beyond London. By the end of 1922, additional stations had opened in Manchester and Birmingham, extending the radio’s reach and laying the groundwork for a national network.

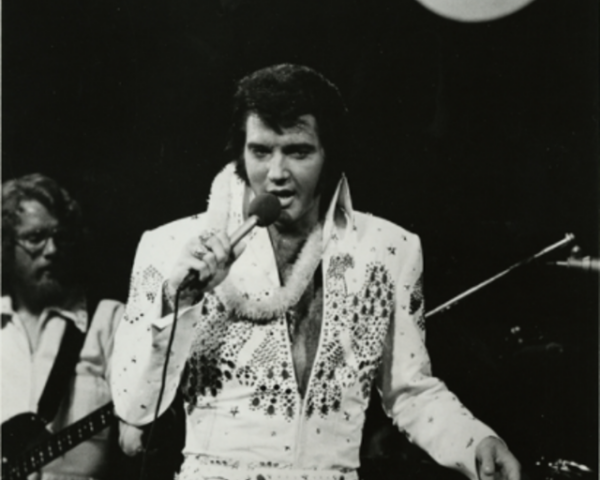

Culturally, the arrival of radio began to unsettle older hierarchies of information and entertainment. For the first time, ordinary Britons — regardless of class — could hear the same music, the same lectures, the same news at precisely the same moment. It democratized access to knowledge while simultaneously introducing new debates about taste, propriety, and influence. Clergy worried about moral decline; educators celebrated new opportunities for instruction; politicians, initially skeptical, soon recognized the medium’s potential for shaping public opinion.

What began on November 14 as a small experiment would, within a decade, transform into the British Broadcasting Corporation, a publicly chartered institution committed to serving the nation with distinction, impartiality, and cultural purpose. But in 1922, none of that destiny was fixed. What Britain had on that first evening was something far more fragile: a voice carried across invisible waves, stitching together a country still searching for stability after war.

The broadcast was brief, yet in a modest studio powered by wires, tubes, and ambition, the British Broadcasting Company lit a fuse that would alter the contours of modern communication.