The French Revolution’s descent into ideological fury was neither sudden nor unforeseeable; its logic of purification had been incubating for years. By the autumn of 1793, as the radical Jacobin government tightened its grip on the Republic, the revolutionary promise of liberty and citizenship had curdled into a systematized regime of suspicion. In no place was this more visible than in the Atlantic city of Nantes, where political paranoia fused with anticlerical zeal to produce one of the Revolution’s most chilling episodes: the mass drowning of refractory priests on November 16, 1793.

The backdrop was one of profound civil fracture. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy (1790), which sought to remake the Catholic Church into an arm of the French state, had forced priests to swear loyalty to a revolutionary order many regarded as sacrilegious. Nearly half refused. These “refractory” priests—who insisted their allegiance was to Rome and the universal Church rather than to Parisian committees—became, in Jacobin eyes, counterrevolutionaries in cassocks. And in the Vendée and Brittany, where rebellion flared against conscription and the dismantling of traditional religion, the presence of non-juring clergy was portrayed as a spiritual spark that might reignite civil war.

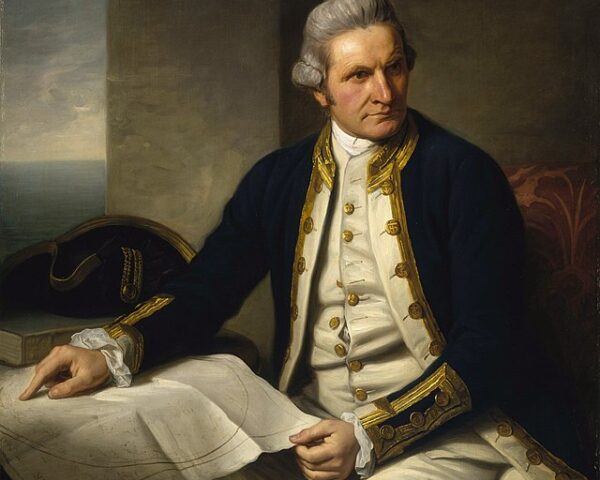

Jean-Baptiste Carrier arrived in Nantes in October 1793 with precisely this fear in mind. A representative-on-mission dispatched by the Committee of Public Safety, Carrier was tasked with suppressing the turbulent region and clearing the overflowing prisons. What he found was a city stretched to the breaking point: refugees fleeing the Vendée war, suspected royalists crammed into makeshift cells, and a local bureaucracy paralyzed by the sheer volume of arrests. Carrier’s response, cloaked in revolutionary rhetoric, would become notorious even among his fellow Jacobins.

On November 16, he ordered roughly ninety refractory priests held aboard a moored vessel to be taken under cover of night to the middle of the Loire River. The priests—elderly, unarmed, some sick—had already endured months of confinement. Many believed they were being transferred to another prison. Instead, once the boat reached a quiet stretch of water, hatches were sealed and the hull was sabotaged. As river water rushed in, the vessel sank, drowning the men inside. This “first noyade,” as it would later be remembered, inaugurated a grim pattern: drowning, being silent, left no firing squad, no audible screams, and no bodies paraded through town. It was a method designed both for efficiency and concealment.

Yet concealment was impossible. Rumors spread quickly, and Carrier—far from denying the act—embraced it. He boasted that the Loire would become the “national bathtub,” a purifying instrument of the Revolution. Over the following weeks, a series of further noyades killed hundreds more: prisoners, suspected royalists, women, children, and ordinary citizens caught in the widening net of suspicion. In total, upward of 2,000 people may have been drowned at Nantes between late 1793 and early 1794.

Even within the brutal climate of the Terror, Carrier’s actions disturbed many. Deputies in Paris, though committed to rooting out counterrevolutionary threat, recognized that the violence at Nantes was not simply excessive but corrosive to the Revolution’s own claim to moral authority. By the time Carrier was recalled to Paris in early 1794, the political tides were already shifting. After Robespierre’s fall later that summer, Carrier became an emblem of revolutionary excess—conveniently isolated, tried, and executed by guillotine in late 1794.

The drowned priests of November 16 stand today as stark evidence of how revolutions, in their bid to remake society, often turn coercion into virtue and violence into necessity. The noyades of Nantes were not a spontaneous overflow of rage; they were the product of ideological certainty, bureaucratic pressure, and a belief that political purification required literal cleansing. In that sense, the Loire became the Revolution’s mirror—reflecting not the radiant promises of 1789 but the darker logic of a government convinced that dissent and treason were indistinguishable.