On November 23, 534 BC, in the city of Athens during the festival of the Great Dionysia, a figure from the rural deme of Icaria stepped onto a wooden platform and changed the trajectory of Western storytelling. His name was Thespis. By tradition—and according to later ancient commentators—he became the first person in history to portray a distinct character on stage. In that moment, the art form that would become drama, theater, and all forms of performed narrative began its recognizable life.

To appreciate the magnitude of Thespis’s innovation, one must imagine the Athenian world of the sixth century BC. Before Thespis, performances honoring Dionysus consisted of choral hymns—dithyrambs—sung by a collective voice. The chorus narrated, lamented, and celebrated, but always as a unified group, never as individuals. There was no dialogue, no character, no dramatic conflict, and certainly no actor stepping forward to speak as someone other than himself. Poetry existed, of course, and so did ritual storytelling, but the separation between narrator and protagonist had not yet been made explicit through performance.

Thespis altered this ancient equilibrium. According to later accounts preserved by writers such as Aristotle and the lexicographer Suda, he introduced a performer who could temporarily step out of the chorus to speak lines that belonged to a character. This innovation required the invention of dramatic impersonation—what would later be called hypokrisis, the act of answering or responding, from which the English word “hypocrite” ultimately derives. Instead of the chorus telling a story collectively, a single performer could embody the hero, the god, or the villain. In effect, Thespis created the possibility of dialogue, tension, and theatrical illusion.

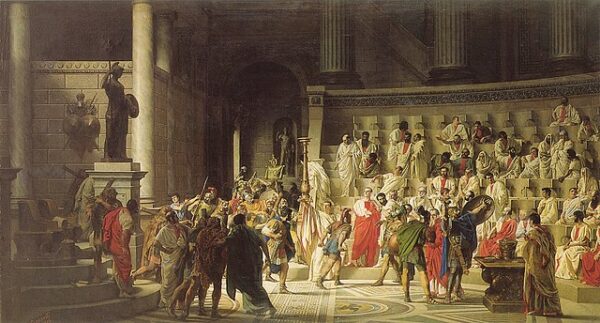

The moment occurred during the City Dionysia, a newly reorganized festival that would, in later centuries, become the most prestigious platform for dramatists like Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. The date—534 BC—is often treated as traditional rather than strictly documented, but scholars widely accept it as the year in which the archon Pisistratus instituted formal competitions for tragedy. Thespis, competing in this earliest recorded contest, is said to have won the first prize. His victory symbolized not only personal achievement but the institutional birth of tragedy as a competitive art.

What exactly Thespis performed remains unknown. No script survives, and the reports of ancient writers often blend speculation and legend. Some accounts suggest he introduced rudimentary masks, perhaps made of linen or stiffened fabric, to help distinguish characters. Others suggest he traveled from place to place with a portable wagon—the skênê—that functioned as a mobile performance stage. This wagon became so iconic in later tradition that the Roman-era word thespian—meaning actor—derives from his name, preserving the idea that the originator of acting roamed from village to village carrying the new art form with him.

Regardless of the details, Thespis’s leap was conceptual as much as practical. By creating a performer who could represent someone else, he opened a space between the real and the fictional. The actor no longer merely recited; he embodied. The chorus no longer spoke as a monolithic voice; it could react to an individual. And the audience no longer observed ritual storytelling; it witnessed enacted narrative. These distinctions, seemingly small in the moment, became foundational to Western dramatic tradition.

The centuries following Thespis’s debut would bring rapid evolution. Aeschylus added a second actor, creating more complex dialogue. Sophocles added a third, enabling intricate dramatic conflict. Euripides deepened psychological realism. Comedy developed alongside tragedy, and both genres spread throughout the Mediterranean world. Yet each innovation built upon the initial conceptual break introduced by Thespis on that long-ago November day.

Modern scholarship acknowledges that Thespis, like many founding figures, lives partly in the realm of myth. His historical outline is blurry, and his biography is largely reconstructed from later references. But the historical consensus remains that sometime around 534 BC—traditionally on November 23—Athenian performance underwent a decisive transformation. A human being stepped forward, put on a mask, and spoke as someone else. In doing so, Thespis of Icaria not only inaugurated the dramatic arts but reshaped the way human beings tell stories, imagine themselves, and understand the world.