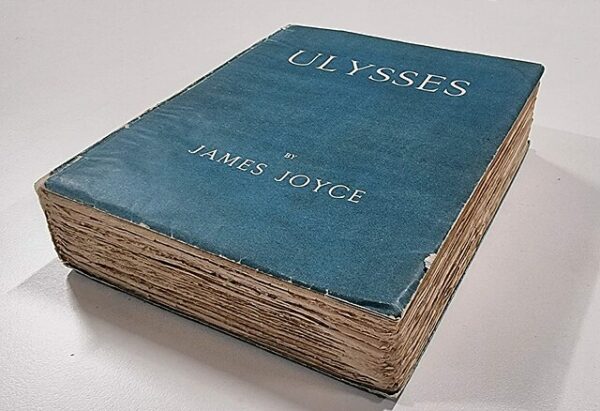

On December 6, 1933, United States District Judge John M. Woolsey issued a landmark ruling in United States v. One Book Called Ulysses, declaring that James Joyce’s modernist novel Ulysses was not obscene under federal law and could therefore be legally imported and sold in the United States. The decision, which emphasized literary merit over isolated passages of sexual or vulgar imagery, marked a profound shift in American jurisprudence on censorship and free expression.

The controversy around Ulysses had been building for more than a decade. Serialized excerpts of the novel had appeared in The Little Review, an American literary magazine, in 1918–1920. The magazine’s editors, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, were prosecuted for obscenity for publishing a section of the “Nausicaa” episode, which depicted the protagonist Leopold Bloom’s voyeuristic erotic reverie. Found guilty, Anderson and Heap received fines, and the serialization of Ulysses in the United States came to an abrupt end. The complete book, published in Paris in 1922, was banned from importation into the United States under the Customs Act.

That legal barrier held until Bennett Cerf, co-founder of Random House, decided to test it by having a copy of Ulysses seized by Customs officials when he attempted to import it in 1932. Cerf then initiated a suit against the government that would require a court to evaluate the book in its entirety rather than by selective quotation. The case was assigned to Judge Woolsey, who read the entire novel with painstaking care—three times, he later wrote—to assess both its character and artistic intention.

Woolsey’s ruling rejected the traditional standard used in obscenity prosecutions, which treated individual passages of sexual frankness as sufficient grounds for condemnation. He insisted instead on evaluating Joyce’s work as a whole, arguing that isolated sexual elements were subordinate to artistic purpose. Woolsey conceded that Joyce employed “coarse language and explicit sexual content” in certain scenes, but he insisted these were not gratuitous. Rather, Joyce sought to replicate interior consciousness with unprecedented realism, capturing “the unvarnished stream of thought” that constituted the foundation of modernist experimentation.

The judge emphasized that readers encountering vulgarity in Ulysses would not experience it as incendiary or prurient, but as part of a broader literary effort to portray ordinary experience. “In Ulysses,” Woolsey wrote, “the words which are criticized as obscene are old Saxon words known to almost all men, and, I venture, to many women, and are such words as would be naturally and habitually used, I believe, by the types of folks whose actions Joyce is endeavoring to describe.” The sensory and erotic elements were, he concluded, integral to Joyce’s fidelity to human psychology.

Woolsey’s formulation became one of the most quoted lines in American obscenity law: “I find that Ulysses is a sincere and honest book, and I think that the criticism of it is entirely unjustified.” He believed that literature must be evaluated on whether it appealed to “lustful thoughts,” and he held that Joyce’s intention was artistic, not pornographic. In declaring the book permissible for importation, Woolsey emphasized that no intelligent reader could regard it as intended to “promote sexual impulses.”

The ruling set a transformative precedent. It marked one of the earliest judicial acknowledgments that artistic merit must be assessed holistically, and that candid depictions of sexuality do not inherently violate community standards. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed Woolsey’s decision in 1934, and Ulysses soon entered the American literary mainstream.