On December 25, 1831, as plantation owners across Jamaica gathered to celebrate Christmas, thousands of enslaved men and women quietly set in motion one of the most consequential uprisings in the history of Atlantic slavery. What became known as the Great Jamaican Slave Revolt—or the Baptist War—was not a spontaneous outburst of violence, but a coordinated, ideologically driven challenge to a system that had governed the island for more than a century. By its peak, as many as one in five enslaved people on the island had mobilized in an ultimately unsuccessful fight for freedom, shaking the foundations of slavery throughout the British Caribbean.

Jamaica in the early nineteenth century was the crown jewel of the British Caribbean, a brutally efficient sugar-producing colony built on coerced labor. Enslaved Africans vastly outnumbered whites, and plantation discipline was enforced through violence, surveillance, and the ever-present threat of punishment. Yet the island was also deeply connected to the wider currents of the Atlantic world. Enslaved people heard rumors of abolitionist debates in Britain, followed missionary preaching, and drew conclusions of their own about the moral legitimacy—and fragility—of slavery.

At the center of the 1831 revolt stood Samuel Sharpe, an enslaved Baptist deacon whose literacy and religious authority gave him unusual influence. Sharpe believed slavery was incompatible with Christian teaching and was convinced that freedom had already been granted by Britain but was being withheld by colonial elites. His initial plan was not violent rebellion but a massive, island-wide labor strike beginning on Christmas Day, designed to force concessions through economic pressure. If planters refused to comply, Sharpe and his followers were prepared to escalate.

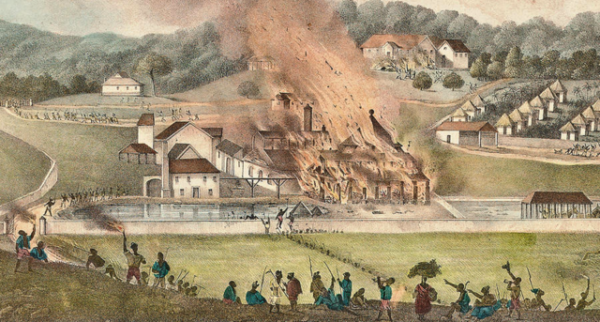

The strike spread rapidly across western Jamaica, particularly in the sugar parishes of St. James, Trelawny, and Hanover. When negotiations failed and tensions mounted, plantations were set ablaze, cane fields destroyed, and estate infrastructure targeted. Although relatively few whites were killed, the material damage was enormous, and colonial authorities quickly recognized the scale of the threat. British troops and local militias were mobilized, and martial law was declared.

The rebellion was crushed within weeks by overwhelming force. In the aftermath, the reprisals were swift and merciless. More than 300 enslaved people were killed, many executed after summary trials, and hundreds more were flogged or imprisoned. Samuel Sharpe himself was captured, tried, and hanged in May 1832. His final words reportedly affirmed his belief that he had acted justly and that slavery would not endure.