On December 26, 1799, just ten days after the death of George Washington, the United States Congress convened in solemn session to honor the man whose life had become inseparable from the nation’s founding. It was there that Henry Lee III—Revolutionary War cavalry commander, former Virginia governor, and close personal friend of Washington—delivered what would become the most enduring epitaph in American political history.

Lee’s words distilled Washington’s career into a single, immortal line: “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” In one sentence, Lee captured not merely Washington’s accomplishments, but the moral architecture of the early republic itself.

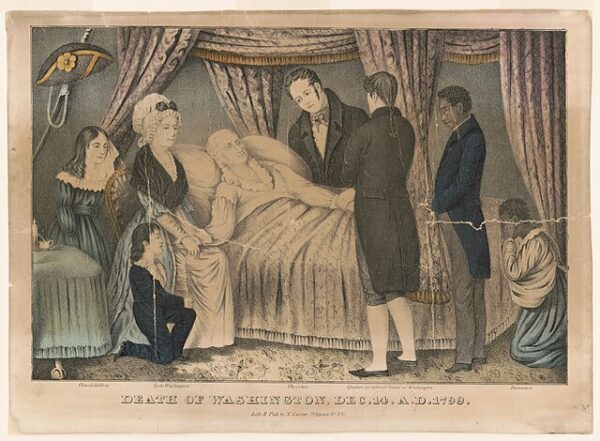

The timing mattered. Washington had died on December 14, 1799, at Mount Vernon, plunging the young nation into its first collective mourning. The United States was barely a decade removed from ratifying the Constitution. Political factions were hardening. Foreign entanglements loomed. The republic’s durability was still unproven. Washington’s death forced Americans to confront an unsettling question: could the country endure without the singular figure who had held it together?

Lee’s eulogy was, in part, an answer to that fear.

When Lee spoke before Congress, he was not merely praising a fallen leader. He was articulating a national creed. “First in war” recalled Washington’s role as commander of the Continental Army—his endurance through defeat, privation, and near-collapse, and his ultimate triumph at Yorktown. Washington’s greatness in war was not tactical brilliance alone, but character: restraint with power, patience under pressure, and loyalty to civilian authority even when the army teetered on mutiny.

“First in peace” carried even greater weight. Washington’s voluntary resignation of his commission in 1783 had stunned the world. Kings did not relinquish armies; conquerors did not return to private life. Yet Washington did—and then did so again after two terms as president. In an age defined by revolutions that devoured themselves, Washington set a precedent that power was a trust, not a possession. The peaceful transfer of authority became not an accident of history, but a constitutional expectation.

Finally, “first in the hearts of his countrymen” spoke to something less tangible but no less decisive: legitimacy. Washington commanded affection across regional, economic, and ideological lines. He was not flawless—no human leader is—but he was trusted. That trust served as a stabilizing force during the fragile early years of the republic, when institutions were still learning how to function without tearing themselves apart.

Lee’s eulogy did more than memorialize Washington; it canonized a standard of leadership. It implied that American greatness would not be measured solely by victory or prosperity, but by virtue, restraint, and public trust. In elevating Washington as a model, Lee implicitly warned future leaders that ambition unchecked by character would threaten the republic Washington helped create.

The phrase itself quickly escaped the walls of Congress. It entered textbooks, speeches, monuments, and civic memory. Generations of Americans would repeat it, not as empty praise, but as shorthand for an ideal: leadership that serves rather than dominates, that unites rather than exploits.

More than two centuries later, Lee’s words endure because they describe not only who Washington was, but what the American experiment aspired to be.