On December 28, 1835, a violent confrontation in central Florida marked the opening shots of one of the longest, costliest, and most politically revealing conflicts between the United States and an Indigenous nation: the Second Seminole War. At its center stood Osceola, a defiant Seminole leader whose resistance crystallized Native opposition to federal Indian removal policy and exposed the moral and strategic contradictions of American expansionism in the Jacksonian era.

The immediate catalyst came amid escalating tensions over the enforcement of the Treaty of Payne’s Landing (1832), which required the Seminoles to abandon their Florida homeland and relocate west of the Mississippi River. Though federal officials claimed the treaty had been agreed to, many Seminole leaders disputed its legitimacy, arguing it had been signed under coercion and without proper tribal consent. Osceola emerged as a central figure in this resistance—not a hereditary chief, but a charismatic war leader whose authority rested on personal resolve, rhetorical power, and an unyielding refusal to submit.

On the morning of December 28, U.S. Army troops under Major Francis Dade marched north from Fort Brooke toward Fort King, near present-day Ocala. The column was ambushed by Seminole warriors concealed in the pine flatwoods. In what became known as the Dade Massacre, more than 100 soldiers were killed, with only a handful surviving. Though Osceola did not personally command the ambush, the attack symbolized the broader uprising he helped inspire. On the same day, Osceola himself killed Wiley Thompson, the federal Indian agent at Fort King, a calculated act that severed any remaining pretense of negotiation.

The outbreak of full-scale war stunned Washington. Federal authorities had assumed Seminole resistance would collapse quickly, as had many earlier removal campaigns. Instead, the conflict dragged on for nearly seven years, drawing in thousands of U.S. troops and costing the federal government tens of millions of dollars. The Seminoles—never numbering more than a few thousand—used Florida’s swamps, hammocks, and dense forests to devastating effect, conducting guerrilla warfare that confounded conventional military strategy.

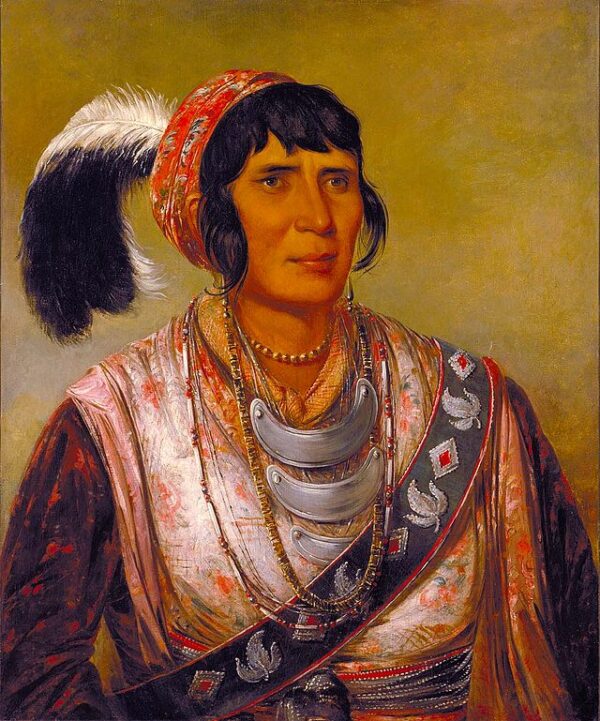

Osceola’s role during the early phase of the war elevated him into a national symbol. To white Americans, he was alternately portrayed as a savage insurgent or a romantic freedom fighter. To the Seminoles, he embodied resistance itself. His defiance challenged the prevailing assumption that Native nations would inevitably yield to U.S. authority. In speeches and actions alike, Osceola rejected removal not merely as a logistical hardship, but as an existential injustice—a demand that his people erase themselves for the convenience of American settlers.

The Second Seminole War also revealed the limits of U.S. power. Despite overwhelming manpower and resources, the Army struggled to impose control. Disease, unfamiliar terrain, and low morale plagued federal forces. The war exposed the human costs of removal policy, both for Native communities and for American soldiers sent to enforce it. Even among some contemporaries, the conflict raised uncomfortable questions about the legitimacy of a republic waging war to expel an entire people from their ancestral land.

Osceola’s resistance ended not on the battlefield but through deception. In 1837, he was captured under a false flag of truce and imprisoned at Fort Moultrie in South Carolina, where he died of illness less than three months later. His death did not immediately end the war, but it deprived the Seminoles of one of their most galvanizing figures. Yet the Seminoles were never fully defeated. The community remains in Florida to this day, their survival a rare exception to removal.