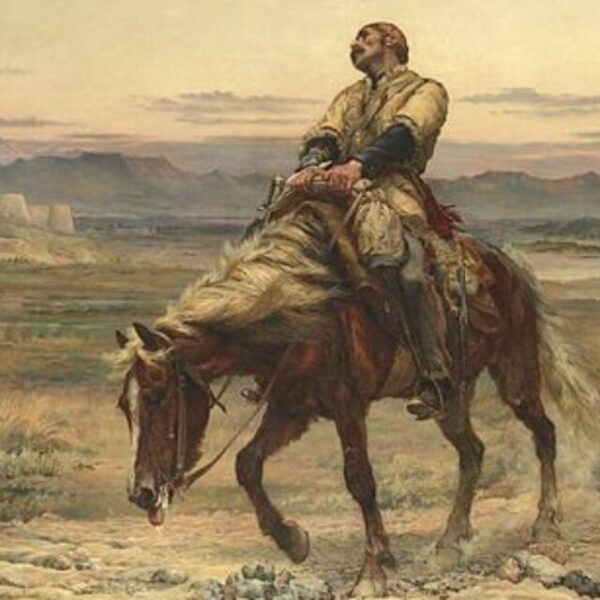

Amid one of the most catastrophic retreats in British military history, a single exhausted rider emerged from the mountain passes of eastern Afghanistan. Slumped in the saddle, wounded, frostbitten, and barely conscious, William Brydon, an assistant surgeon in the British East India Company Army, reached the fortified garrison of Jalalabad. When questioned by anxious officers, Brydon is said to have replied simply that he was “the army”—the lone apparent survivor to reach safety from a column of roughly 4,500 soldiers and some 12,000 camp followers annihilated during the retreat from Kabul. His arrival on that January day became an instant legend, a stark symbol of imperial overreach and the brutal realities of Afghan resistance.

The disaster unfolded during the First Anglo-Afghan War, a conflict rooted in Great Power rivalry and British fears of Russian expansion toward India. Determined to secure its northwest frontier, Britain deposed Afghan ruler Dost Mohammad Khan and installed Shah Shuja Durrani as a client monarch. The occupation of Kabul initially appeared successful, but the settlement rested on fragile foundations: political arrogance, cultural misunderstanding, and a profound misreading of Afghan hostility toward foreign troops and imposed rule.

By late 1841, simmering resentment exploded into open revolt. Afghan fighters harassed British forces in Kabul, assassinated senior officials, and cut supply lines. Facing mounting pressure and dwindling provisions, Major General William Elphinstone agreed to evacuate the city under promises of safe passage to Jalalabad. Those assurances proved hollow. In early January 1842, the column—soldiers, Indian sepoys, women, children, servants, and merchants—set out into snow-choked mountain passes, ill-prepared for winter warfare and dependent on the goodwill of local tribes that quickly turned hostile.

What followed was a slow-motion catastrophe. Afghan marksmen fired from the heights; tribesmen ambushed stragglers; exposure, hunger, and exhaustion claimed the weak. Each day the column shrank as thousands were killed or captured. Brydon, though a medical officer rather than a frontline commander, fought alongside the troops and suffered multiple wounds, including a saber blow to the head that fractured his skull. His survival owed less to battlefield heroics than to endurance, chance, and relentless forward movement—an almost mechanical refusal to stop riding despite injuries that would have incapacitated most men.

When Brydon reached Jalalabad on January 13, 1842, the garrison feared the worst but still hoped others might follow. None did. While a small number of prisoners survived captivity and were later released, Brydon was the only member of the retreating force to arrive independently at the British lines. News of the annihilation of the Kabul column sent shockwaves through London and across the empire, puncturing assumptions about British military invincibility and exposing the limits of imperial power in unfamiliar terrain.

The episode soon entered popular memory through art and literature, most famously in Lady Butler’s painting The Remnants of an Army, which depicts Brydon as a solitary figure approaching safety against a bleak Afghan landscape. The image distilled a larger truth: Afghanistan was not a passive stage for imperial maneuvering, but a fiercely contested land capable of humbling even the world’s strongest empires.