On January 15, 1777, in the depths of the American Revolutionary War, a rugged, contested frontier known as New Connecticut—today’s Vermont—took a step few dared: it declared itself an independent polity. The declaration did not pledge allegiance to Britain, nor did it seek immediate admission to the rebelling colonies. Instead, it announced a separate course, asserting sovereignty amid imperial collapse and colonial uncertainty. The result was the Vermont Republic, an experiment in self-government that would endure for fourteen years before joining the United States.

The roots of this declaration lay in land—and in conflict. For decades, the territory between New York and New Hampshire had been claimed by both colonies. New Hampshire governors issued land grants west of the Connecticut River; New York authorities later voided them, demanding new titles and fees. Settlers who held New Hampshire grants saw this as legal robbery. Tensions escalated into violence, with New York courts attempting to evict families and armed bands mobilizing in resistance. By the time imperial authority frayed in 1775, the dispute had hardened into a local cause with revolutionary overtones.

Militia leaders such as Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys emerged as enforcers of settler claims, blending frontier vigilantism with revolutionary rhetoric. Their early capture of Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775 gave the movement legitimacy and leverage. Yet even as the Continental Congress struggled to coordinate resistance to Britain, it hesitated to intervene decisively in the New York–New Hampshire land quarrel. For the settlers of New Connecticut, independence became a practical solution to a political deadlock.

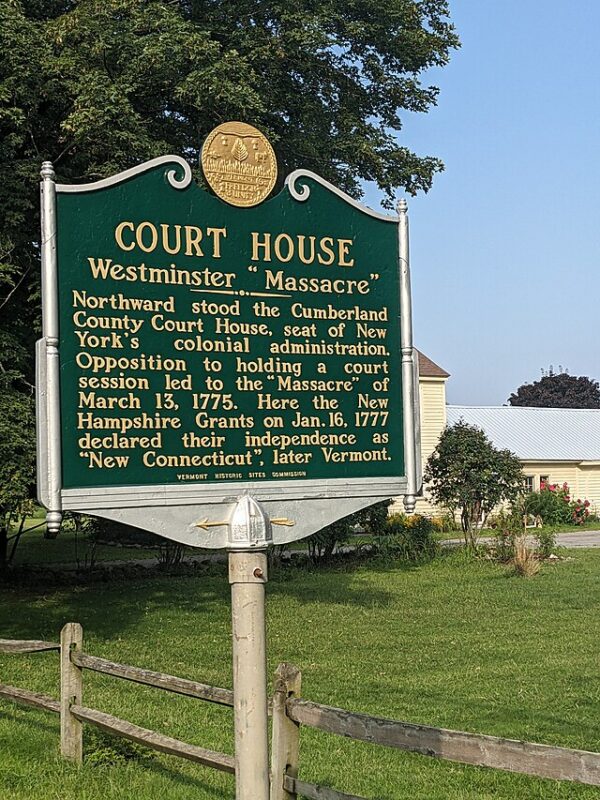

Meeting at Westminster in January 1777—later reconvening at Windsor—the delegates declared that the territory was “a free and independent jurisdiction or state.” The timing was deliberate. The war’s outcome was uncertain; British forces still occupied New York City; and Congress was cautious about alienating powerful states. Declaring independence allowed the new polity to defend its land titles, raise troops, and negotiate from a position of asserted sovereignty rather than as a supplicant caught between rival colonies.

The declaration did not end controversy. New York denounced it as illegal secession; Congress declined immediate recognition. But the new republic pressed ahead. Later in 1777, it adopted one of the most radical constitutions in North America. The Vermont Constitution abolished adult slavery outright, expanded suffrage beyond property holders, mandated public education, and established protections for individual liberty that went beyond those of many existing states. These provisions reflected both Enlightenment ideals and frontier pragmatism: a society of smallholders wary of distant authority and entrenched privilege.

Throughout the war, the Vermont Republic walked a precarious line. It raised militias to defend its borders against British raids from Canada and New York incursions alike. At times, its leaders engaged in controversial negotiations with British officials—often interpreted as tactical feints—to secure prisoner exchanges or deter invasion. Survival, not ideological purity, guided policy. The republic’s very existence depended on maintaining autonomy while the continent’s great powers contested its fate.

Independence also functioned as leverage. By operating as a de facto state—collecting taxes, administering courts, and fielding troops—Vermont demonstrated viability. Its leaders repeatedly petitioned Congress for admission, using stability as evidence that recognition would strengthen, not fracture, the Union. Only after New York finally relinquished its claims, in exchange for a financial settlement, did Congress move forward.

In 1791, Vermont entered the United States as the fourteenth state, the first added after the original thirteen.