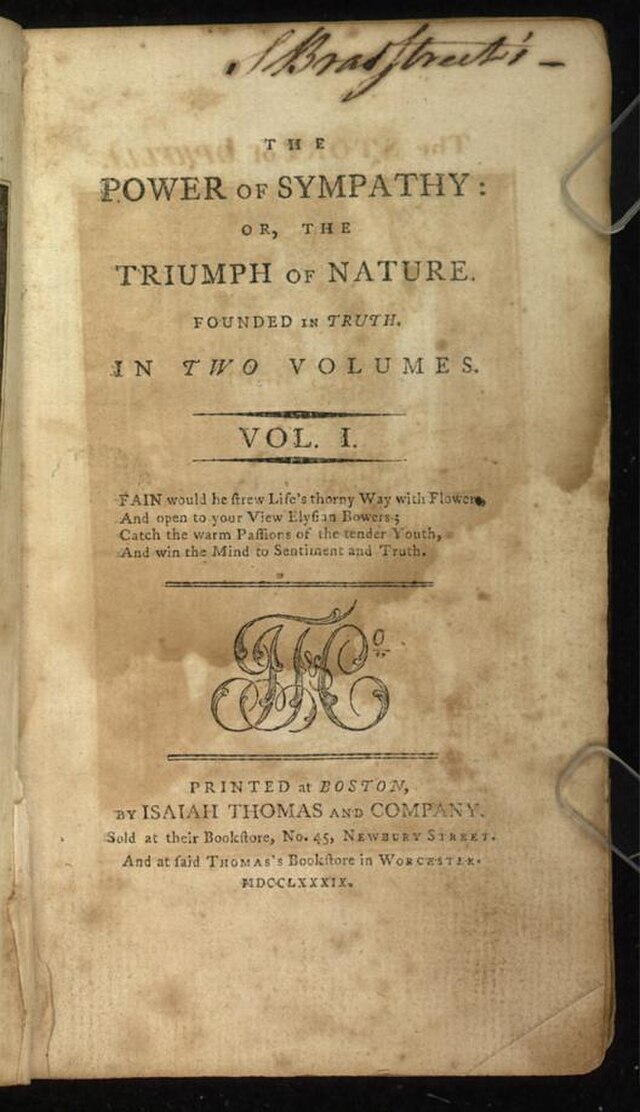

On January 21, 1789, as the United States stood on the cusp of constitutional government, a modest book rolled off a Boston press that would later claim an unexpected distinction. Titled The Power of Sympathy; or, The Triumph of Nature Founded in Truth, the volume is widely regarded as the first American novel—an unassuming literary debut for a nation still defining itself.

Its author, William Hill Brown, was a young Boston writer better known in his lifetime as a poet and essayist. He was just 23 when the novel appeared, working within a culture that viewed fiction warily and novels, in particular, as suspect imports from Europe. Moral reformers warned that such books encouraged idleness and inflamed dangerous passions. Brown’s response was not to rebel against those concerns, but to accommodate them.

The Power of Sympathy is an epistolary novel, told entirely through letters exchanged among its characters, a form familiar to readers of British sentimental fiction. Its plot revolves around courtship, seduction, concealed family ties, and ultimately tragedy. The narrative is designed less to entertain than to instruct. Brown’s subtitle—“Founded in Truth”—was not decorative. It signaled his intent to frame fiction as a moral instrument rather than a corrupting indulgence.

The novel’s central warning is explicit: unrestrained desire leads to ruin. Its characters suffer precisely because social boundaries are crossed and moral discipline collapses. This was not accidental. In the early republic, literature was expected to serve civic ends. A young nation built on republican virtue could not afford art that merely distracted or titillated. Brown sought to prove that imaginative writing could reinforce, rather than undermine, the moral foundations of self-government.

Boston, the site of the book’s printing, shaped both its tone and its ambitions. The city was steeped in Puritan seriousness and revolutionary memory, a place where sermons and political pamphlets dominated the presses. Fiction emerging from that environment was bound to justify itself. Brown’s prose is earnest, sometimes heavy-handed, and openly didactic, reflecting the cultural anxiety surrounding novels in post-Revolutionary America.

Yet the book’s importance lies not in its literary elegance, but in its assertion of cultural independence. By presenting itself as an American story for American readers, The Power of Sympathy suggested that the new republic need not rely entirely on British models for its imaginative life. The settings, social codes, and moral dilemmas are recognizably local. Courtship unfolds within American towns, governed by American expectations about reputation, gender, and virtue.

The novel’s reception was limited. It sold modestly, attracted little contemporary acclaim, and soon faded from public view. Brown himself would not live to expand his experiment. He died in 1793 at the age of 27, leaving behind a small body of work and a single, quiet milestone. Later writers—Charles Brockden Brown, Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper—would develop American fiction with greater confidence and broader appeal.

Still, January 21, 1789, marks a subtle turning point. The Power of Sympathy emerged at a moment when Americans were debating not only how to govern themselves, but how to shape a national culture. The novel reflects those debates in its caution and restraint. It treats emotion as something to be studied, disciplined, and ultimately subordinated to moral reason.

In that sense, the first American novel was not a declaration of artistic freedom, but a negotiation. It asked whether storytelling could exist within a republic that prized virtue over passion and usefulness over pleasure. Brown’s answer was careful, even anxious—but it was affirmative.

The book did not transform American literature overnight. But it established a precedent: Americans could tell their own stories, in their own voice, even while wrestling with inherited fears about imagination and morality. On a winter day in Boston, as the machinery of the new government prepared to come alive, the machinery of American fiction quietly began turning as well.