The following is an adapted excerpt from The Slaveholding Crisis: Fear of Insurrection and the Coming of the Civil War, used with the author’s permission.

On August 30, 1800, a storm likely changed the course of the United States forever when an enslaved blacksmith named Gabriel Prosser saw his plan to overthrow Virginia slavery delayed as flooding caused by rain washed out bridges vital to his plan.

Born in 1776 as the United States declared to the world that “all men were created equal,” Gabriel experienced a different life than most slaves in the South. In an era where merely five percent of enslaved Americans were literate, Thomas Prosser, a tobacco planter and the white man who claimed ownership of Gabriel’s life, taught him how to read and helped him develop a skill in pounding iron. At six feet, three inches tall, he towered above most who met him. Many in Richmond’s black community saw him as a natural leader. Whites too perceived a commanding quality in the blacksmith, considering him to be enterprising, independent, and intelligent. However, few worried about his potential as a leader of rebellion. He was an American, loyal, and content with the few extra freedoms he received for having skill with the anvil and hammer, they presumed.

Large slave revolts evolved over time, not from impulse like proslavery intellectuals insisted, but with careful planning. Although Gabriel actively resisted slavery when he attempted to steal from a farm and fought a slaveholder, his actions on the Johnson plantation only served as a starting point. He tested the resolve of the planters who enslaved him and believed that his survival exposed a weakness in the slaveholding class. A year later, the two accomplices who had once helped him pilfer a pig enlisted in his army. They targeted the heart of the Commonwealth of Virginia for their battle and wanted to fight for more than a few slices of ham. This time freedom stood as the final reward.

Talk of overturning the status quo filled the air during the spring of 1800. White citizens openly debated John Adams versus Thomas Jefferson. Some eventually referred to the election results as “the Revolution of 1800.” As the campaign occupied the thoughts of voters, Gabriel walked the streets of Virginia’s capital with a different societal transformation in mind. To begin, the blacksmith concocted a way to free himself and his neighbors. Then, in his shop at Brookfield plantation, a place where he turned iron into the tools of slaveholders, the insurrectionist leader unveiled his design for liberty to Solomon and another friend. Gabriel stated his goal clearly: he planned the total overthrow of slavery in the Old Dominion.

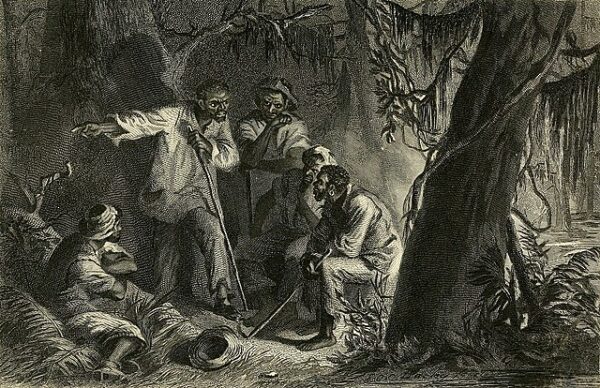

The small audience listened intently as Gabriel laid out his blueprint for toppling the master class small audience. He appealed to the men in attendance by calling on them to protect their wives and children from slavery’s terrible reach. For months, the ironworker and a few compatriots turned the blades of wheat scythes into swords for battle. When the time came, Gabriel planned to gather his army of Richmond slaves in his shop or the surrounding woods. The conspirators envisioned hundreds of soldiers carrying weapons. After wreaking revenge on Thomas Prosser and Absalom Johnson by taking their lives, the outfit of insurgents intended to ride on horseback towards the capital in the middle of the night. There, he expected his allies—emboldened by the seizure of one of Virginia’s oldest cities—to join him. The fight for liberty would begin.

Once inside the city, the large group needed to split into three platoons, choreographing their movements to make the biggest impact against the defenses of the planter elite. The first set planned to take weapons stored in the Capitol before capturing James Monroe as he slept in the Governor’s Mansion. Another had to start fires, setting the warehouse district ablaze and causing a distraction on the opposite side of the city. A final detachment was assigned the task of fortifying the main entrance to the state capital, establishing defensive positions in preparation for the inevitable attempt by slaveholders to reclaim the city. Gabriel’s revolution relied on timing and precision. This would be no typical uprising easily put down by plantation owners. Gabriel expected to ransom Virginia’s capital for freedom.

Significantly, Gabriel did not distinguish a stark racial divide in Virginia. He wanted to kill slaveholders exclusively. Like insurrectionists in the French West Indies, he imagined his call for citizenship to serve as a catalyst for poor whites—also excluded from the political power—to join his rebellion. Only those who directly enslaved others would feel his wrath. Gabriel viewed white nonslaveholders as potential compatriots in a battle against the master class. The insurrection leader planned to carry a banner inscribed with the words “death or Liberty,” a phrase whites believed served as an inversion of Patrick Henry’s famous comment, but may easily have come to Gabriel’s mind because of its common usage during the Haitian Revolution. “Liberte Ou La Mort” had been a slogan during the fighting in the French Caribbean and eventually headlined Haiti’s declaration of independence written but a few years later. Gabriel understood that success offered the only way for his survival. Freedom was worth the risk.

On August 30, 1800, the night designated for the uprising, Gabriel readied to meet his troops, but only a handful arrived. That evening the clouds opened and a downpour drenched eastern Virginia. Some whites in Richmond noticed that, unlike most Saturday nights when the enslaved from the rural areas came into town, many of the black Americans who lived in the city seemed to be trying to leave the capital. With such heavy thunder echoing across the countryside, they paid little attention to the unusual behavior. As the river rose from the deluge, the wooden bridges connecting Brookfield to the rest of the city became impassable. Only a small number of Gabriel’s recruits trudged through the muddy roads to assemble at the assigned meeting place. With fewer numbers than anticipated, the leader of the revolt decided to reschedule his plot, postponing the attack until ensuing night. The storm had given white slaveholders an extra night of respite. The blacksmith-turned-revolutionary expected to mount his rebellion the following day.

The delay caused some of Gabriel’s crew to have misgivings about the plan. Making the rainy trip to the countryside only to see a handful of men mustered left some of the rebels discouraged. Pharaoh, an enslaved craftsman from a neighboring plantation, changed his mind about participating in the revolt. Unlike Gabriel and several other members of the insurrectionary conspiracy, Pharaoh had a long and close relationship with the family of the slaveholder who owned his life, Mosby Sheppard. Four years earlier, he remembered, Sheppard had consented to a slave’s request to purchase his own freedom for a discounted price. Maybe, Pharaoh likely thought, the slaveholder would do it again if he revealed Gabriel’s plot. He found himself with a choice: betraying his friends for potential freedom or risking his life in an attempt at striking a deathblow to slavery.

Pharoah chose to out the secret plan. When Governor James Monroe was informed of the conspiracy he immediately took measures to secure Richmond, ordering weapons moved away from the capitol and into the penitentiary, a building more easily defended. Next, he mobilized a number of regiments in the state militia. Fearing that whispers of an oncoming slave revolt might generate panic, Monroe tried to mask the particulars of the situation from the public. Finally, he launched a search party for the insurrectionists, which captured collaborators working with the blacksmith. Within ten days, roughly thirty conspirators—though not Gabriel—had been found and arrested.

Gabriel and dozens of his fellow revolutionaries were executed the following October.