On January 27, 1820, at the outer edge of the known world, a Russian naval expedition pressed south through ice-choked seas and altered humanity’s map of the planet. Commanded by Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Petrovich Lazarev, the voyage approached what is now recognized as the Antarctic coast—marking the first documented sighting of the Antarctic continent.

For centuries, the idea of a southern landmass had hovered between theory and fantasy. Classical geographers imagined a terra australis to balance the Northern Hemisphere; Renaissance cartographers drew it boldly, if vaguely, across the bottom of the world. By the late eighteenth century, those visions had largely collapsed under empirical pressure. Captain James Cook’s circumnavigation of the Southern Ocean shattered hopes of a mild southern continent, yet even Cook conceded that a frozen land might still exist beyond the ice he could not breach.

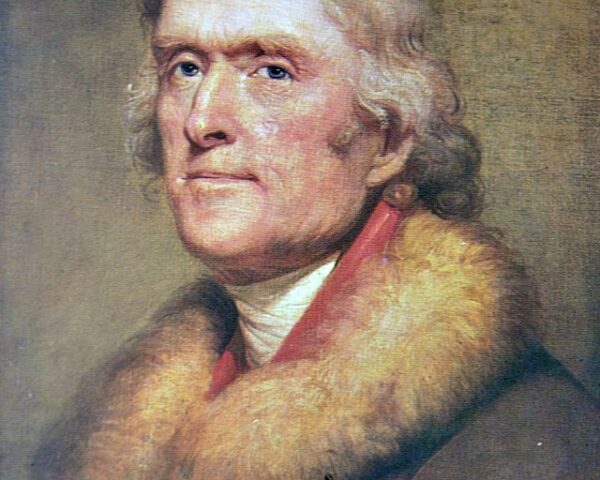

That unresolved possibility became Russia’s opening. In 1819, Tsar Alexander I authorized a naval expedition not merely to chase rumors but to settle geography itself. Bellingshausen, a seasoned officer who had previously sailed with Cook, was given command. Lazarev, younger but formidable, captained the second vessel. Together, they were tasked with pushing south, charting unknown waters, and bringing scientific rigor to a region defined by conjecture.

Their progress was slow and punishing. The Southern Ocean offered no drama—only attrition. Fog erased horizons. Ice closed lanes as soon as they appeared. Sails stiffened with frost; instruments balked in the cold. Navigation became an exercise in patience and precision. Yet Bellingshausen’s logs were meticulous, recording positions and observations with a care that would later prove decisive.

On January 27—January 16 by Russia’s Julian calendar—the expedition reached nearly 70 degrees south latitude. There, through broken ice and low cloud, the officers observed a vast, continuous ice formation rising from the sea. This was no drifting pack ice. Bellingshausen described it as an ice-covered shore, an immense shelf backed by land. The distinction mattered. In polar navigation, everything depends on whether ice moves—or does not.

They did not land. They could not. The ice made any approach suicidal. Nor did they declare a theatrical “discovery.” Bellingshausen was cautious, even restrained, aware of how easily polar mirages could deceive experienced sailors. Instead, he wrote, measured, and charted. The conclusion emerged gradually and repeatedly: this was land—fixed, extensive, and unmistakably continental.