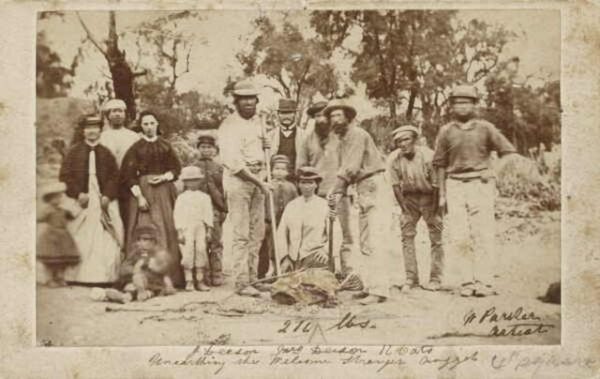

On February 5, 1869, in the small Victorian settlement of Moliagul, two itinerant miners made a discovery so improbable that it bordered on myth. Digging just below the surface of the red Australian soil, John Deason and Richard Oates unearthed the largest alluvial gold nugget ever recorded—a colossal mass later christened the Welcome Stranger. Weighing roughly 72 kilograms (about 160 pounds) before trimming, the nugget stunned a world that believed the age of spectacular gold finds was already fading into memory.

The discovery came decades after the initial frenzy of the Victorian goldfields had transformed Australia. Gold had been found in Victoria in 1851, triggering one of the great global migrations of the 19th century. Prospectors poured in from Britain, Ireland, continental Europe, China, and the United States, reshaping the colony’s demographics, economy, and political life. By the late 1860s, however, the easy pickings were thought to be long gone. Deep quartz mining had replaced surface finds, and many believed the romantic era of nuggets and windfalls was over.

The Welcome Stranger shattered that assumption in a single stroke. Deason and Oates were working a shallow claim near the base of a tree when their pick struck something immovable. At first, they assumed it was a buried rock. Only after clearing away the surrounding earth did its dull yellow sheen become unmistakable. The nugget lay barely inches beneath the surface—an almost mocking reminder that fortune sometimes hides in plain sight.

Its sheer size created immediate logistical problems. The nugget was too large to be weighed intact on the scales available in nearby Dunolly, the closest service town. To measure its value, the miners were forced to break it apart, a practical decision that forever deprived the world of seeing the nugget in its original form. Even so, the gold yielded more than 2,300 troy ounces after impurities were removed, making it vastly more valuable than any nugget found before or since.

News traveled quickly, carried by telegraph and newspaper correspondents hungry for sensation. In Melbourne, crowds gathered outside assay offices to glimpse fragments of the treasure. International papers soon followed, and the Welcome Stranger became a global story—proof that Australia’s goldfields still possessed the capacity to astonish. For a brief moment, the discovery reignited dreams of sudden wealth among miners who had resigned themselves to steady, grinding labor.

Yet the nugget’s timing also underscored a historical transition. Unlike the finds of the early 1850s, the Welcome Stranger did not trigger a new rush. The infrastructure of mining had matured; claims were regulated, land was parceled, and large companies dominated deep extraction. Individual prospectors could still strike it rich, but the social upheaval that had accompanied earlier discoveries was no longer possible. The nugget was less a beginning than a spectacular coda.

Economically, the Welcome Stranger symbolized the enduring importance of gold to colonial Victoria. Gold revenues had financed railways, public buildings, and institutions that helped turn a remote colony into one of the most prosperous societies in the British Empire. Politically, the gold rushes had accelerated demands for representation and reform, contributing to the growth of democratic institutions. By 1869, those transformations were largely complete—but the nugget served as a vivid reminder of their origins.

Culturally, the Welcome Stranger entered Australian folklore almost immediately. It embodied a particular strain of national mythology: the belief in luck earned through hard work, persistence, and an intimate knowledge of the land. That it was found by two working miners—rather than a company—helped cement its legend. Even today, replicas and illustrations stand in for the lost original, anchoring the story in collective memory.

More than a century and a half later, the Welcome Stranger remains unmatched. It stands as the final, thunderous echo of the 19th-century gold rush—a moment when history, chance, and human effort converged just beneath the soil of rural Victoria, reminding the world that even in an age of diminishing frontiers, the earth could still deliver astonishment.