On February 7, 1812, the most powerful earthquake in a relentless series of seismic shocks struck the frontier town of New Madrid, delivering a convulsion so violent that it reshaped the land, terrified distant cities, and permanently altered American understanding of the continent’s hidden geological forces. Occurring just before dawn, this third and strongest major quake of the winter capped one of the most extraordinary natural disasters in U.S. history.

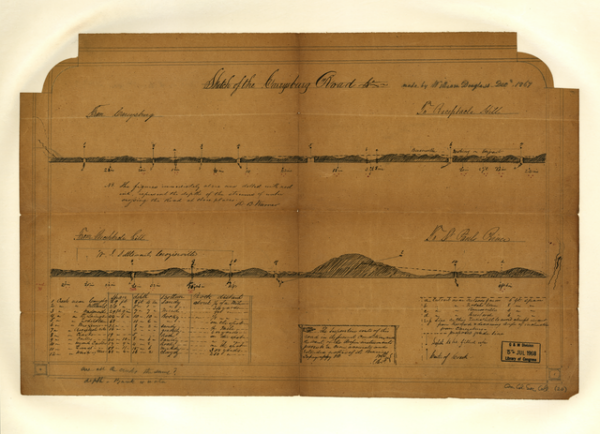

The New Madrid earthquakes unfolded between December 1811 and February 1812, when the central Mississippi Valley—then sparsely settled but increasingly important to westward expansion—was rocked by repeated tremors. The February 7 event, now estimated at magnitude 7.5 to 7.7, surpassed even the devastating January shock that preceded it. Unlike earthquakes along the Pacific coast, this rupture occurred deep within the North American plate, along what is now known as the New Madrid Seismic Zone, making its effects unusually widespread.

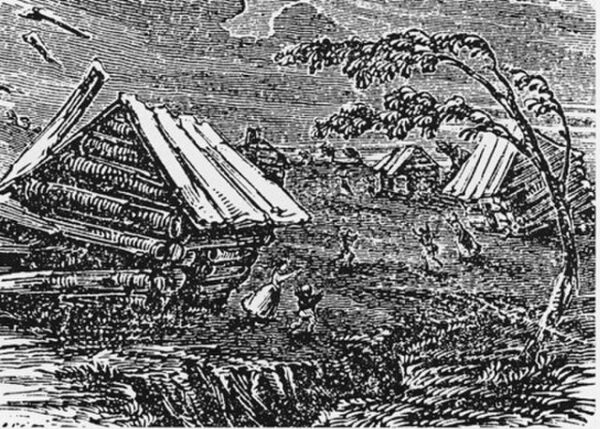

Eyewitness accounts described a landscape in chaos. The ground heaved in rolling waves; trees snapped or were violently uprooted; fissures opened and swallowed cabins whole. Sections of the Mississippi River appeared to run backward as massive seismic waves displaced water and altered the riverbed. Entire tracts of land subsided while others rose abruptly, creating new lakes and marshes almost overnight. Reelfoot Lake in present-day Tennessee, one of the most enduring legacies of the quakes, was formed as forests sank beneath floodwaters.

The quake struck a population ill-prepared to comprehend, let alone withstand, such an event. New Madrid itself—then part of the Missouri Territory—was largely destroyed. Residents fled into the winter cold, camping outdoors for weeks as aftershocks continued relentlessly. The psychological toll was profound. Many settlers interpreted the earthquakes as divine judgment, while others feared the land itself was cursed. Churches filled, frontier sermons grew apocalyptic, and some families abandoned the region altogether.

What made the February 7 earthquake especially remarkable was its geographic reach. Tremors were felt as far away as the eastern seaboard. In cities like Boston, church bells rang spontaneously; in Washington, D.C., furniture shook and startled residents rushed into the streets. Chimneys collapsed in Cincinnati and Louisville, hundreds of miles from the epicenter. The soft, sediment-rich soils of the Mississippi Valley amplified seismic waves, allowing them to travel far more efficiently than they would have in rockier terrain.

The earthquakes struck at a formative moment in American history. The United States was on the brink of the War of 1812, its population pushing steadily westward into lands recently acquired through the Louisiana Purchase. The New Madrid disaster exposed the fragility of that expansion and challenged assumptions about the stability of the continent’s interior. Until then, many believed powerful earthquakes were confined to distant, exotic places—or biblical times.

In the aftermath, the federal government quietly confronted the damage. Congress later allowed affected landowners to relocate their claims to more stable ground, an early recognition of natural disaster relief, though limited in scope. Yet scientific understanding lagged behind experience. Without seismology as a formal discipline, explanations remained speculative, blending folk belief, theology, and rudimentary natural philosophy.

Two centuries later, the February 7, 1812 earthquake still looms large in American memory. It remains the strongest known seismic event ever recorded in the continental United States east of the Rocky Mountains. Modern cities now sit atop the same fault system, their infrastructure far more complex—and vulnerable—than the log cabins of New Madrid. The quake stands as a reminder that the heart of North America, though quiet on the surface, is not immune to sudden and transformative violence from below.